Conflict Overview

Haiti experienced catastrophic levels of violence during the reporting period, marking one of the deadliest chapters in its recent history. At least 5,601 people were killed in 2024 as a result of gang violence according to the Office of the United Nations (UN) High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).1OHCHR, ‘Haiti: Over 5,600 killed in gang violence in 2024, UN figures show’, Press release, 7 January 2025. Between July 2024 and February 2025, OHCHR documented 4,239 killings and a further 1,356 serious injuries.2OHCHR, ‘Restoring dignity: A global call to end the violence in Haiti’, News release, 7 April 2025. Conflict further intensified in the first half of 2025, with at least 2,680 people killed between 1 January and 30 May.3OHCHR, ‘Haiti: UN Human Rights Chief alarmed by widening violence as gangs expand reach’, Press release, 13 June 2025.

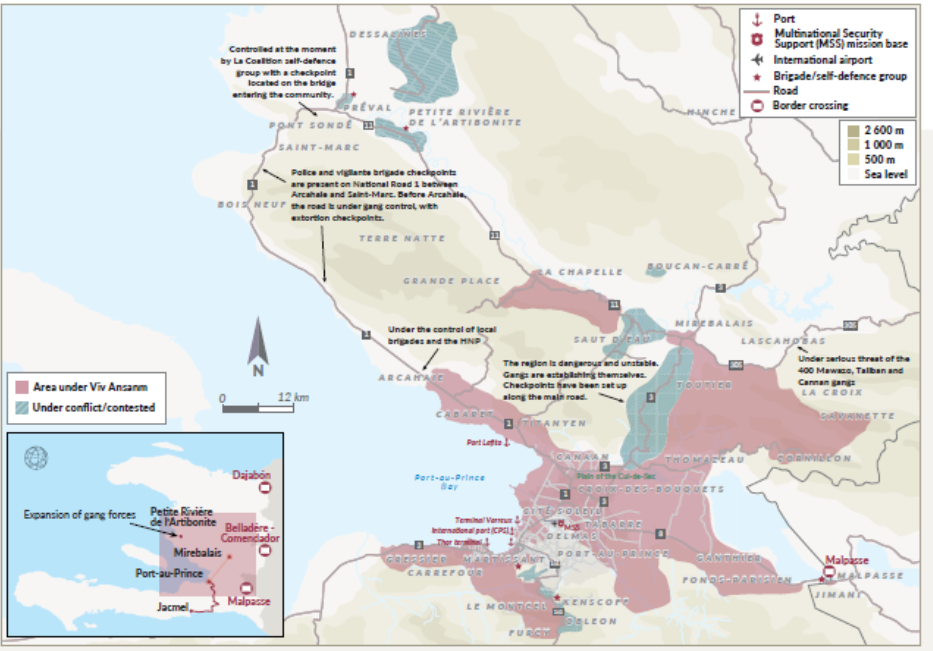

The situation under international law was transformed on 29 February 2024 with the formation of the Viv Ansanm coalition. The coalition, whose title means ‘Living Together’ in Haitian Creole, is a merger of two, previously rival organized gangs: the Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies, led by Jimmy Chérizier (alias ‘Barbecue’); and the G-Pèp (G-People) alliance, led by Gabriel Jean Pierre (alias ‘Ti Gabriel’).4F. Robles, ‘Massacre in Haiti’s Capital Leaves Nearly 200 Dead, U.N. Says’, The New York Times, 8 December 2024. The UN Security Council put Viv Ansanm on its sanctions list in July 2025.5UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions list, July 2025. The coalition reflects significant consolidation of power in Haiti, with members already exerting control over eighty-five per cent of the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince as of October 2024 (as well as several zones just outside the capital).6‘Assessment of progress achieved on the key benchmarks pursuant to paragraph 25 of resolution 2700 (2023), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/711, 1 October 2024, para 3.

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data project (ACLED) noted the widespread ‘scepticism’ at the inception of Viv Ansanm, with many doubting its durability as a result of ‘long-standing rivalries and differences among its members’. But the ‘coordinated Viv Ansanm incursions launched on State institutions on 29 February 2024, which sought to force Prime Minister Ariel Henry’s resignation, ‘marked a turning point and demonstrated the coalition’s ability to adapt, negotiate, and work cohesively toward shared goals.’7S. Pelligrini, ‘Viv Ansanm: Living together, fighting united – the alliance reshaping Haiti’s gangland’, Report, ACLED, 16 October 2024. Indeed, despite internal tensions, the coalition has ‘preserved its cohesion’, demonstrating its ability to manage disputes.8‘From criminal governance to community fragmentation: Addressing Haiti’s escalating crisis’, Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, Policy Brief, Geneva, September 2025, p 14.

The coalition operates through a multi-tiered leadership structure with sub-commanders who lead constituent gangs under the overall leadership of Jimmy Chérizier, who also functions as the spokesperson for the coalition.9‘Viv Ansanm: Comment une coalition de gangs a transformé la violence à Port-au-Prince’, Risk Bulletin No 1, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, July 2024. In November 2024, the Haitian National Police (PNH) stepped up their attacks on Delmas 6, Mr Cherizier’s personal stronghold in the capital. In an hours-long battle on 21 November, PNH armoured cars killed two of his soldiers and captured a Kalashnikov rifle. In a live broadcast, he declared that the PNH tanks had ‘bothered’ the perimeter of his neighbourhoods, aggravating him to the point that he had taken up a weapon himself to start firing at the armoured vehicles. This ‘impetuous act’, he reported, had so alarmed some of the other Viv Ansanm commanders that they had called him by phone to ask him to please be prudent, fall back, and not risk his life.10K. Ives, ‘As Cops Target Lower Delmas, Viv Ansanm Leaders Declare that Haitians are Free to Move around Haiti Again’, Haïti Liberté, 27 November 2024.

On 2 January 2025, Mr Chérizier declared that Viv Ansanm would transform into a political party.11‘1er Janvier 2025: Le groupe criminel “Viv Ansanm” désormais un parti politique’, Kominotek, 3 January 2025. This has not happened. Between 26 and 29 January 2025, Viv Ansanm launched multiple attacks in Kenscoff (West Department), south of Port-au-Prince, aiming to seize control of the area and secure access to the south-east of the country. It is estimated that between 90 and 150 people were killed. The violence also resulted in more than 100 households being destroyed, and the displacement of 3,139 people.12UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions list. By October, the gangs controlled about ninety per cent of the capital.13Y. Yacou, ‘Les États-Unis et l’ONU sanctionnent deux figures clés du crime organisé en Haïti’, Franceinfo, 22 October 2025. Then on 15 November, Chérizier delivered a stark public warning:

Starting this Monday, 17 November 2025, if it’s not necessary to go out, stay at home. All drivers unions, stay at home. All public transport drivers, stay at home. … People who don’t need to, don’t go out into the street. Leave the streets to ‘Viv Ansanm’ and the police so we can confront them.14‘Haïti: Jimmy Cherizier “Barbecue” annonce une contre-offensive de la coalition de gangs “Viv Ansanm” contre la police qui mobilise toutes ses forces’, Franceinfo, 17 November 2025.

In late November 2025, Sunrise Airlines suspended all flights to and from the capital, while the National Port Authority issued a maximum alert due to multiple attacks on Port-au-Prince port facilities.15D. Mohor, ‘Haiti in-depth: The new Gang Suppression Force and what it means for Haitians’, The New Humanitarian, 3 December 2025.

In sum, the coalition’s organized nature, its control of territory, and the continuing violence against the authorities (and civilians) have combined to create a non-international armed conflict under international humanitarian law (IHL).16International Criminal Court, Prosecutor v Bosco Ntaganda, Judgment (Trial Chamber) (Case No ICC-01/04-02/06), 8 July 2019, para 716.

Viv Ansanm attacks have left most of the population in the capital facing a humanitarian crisis. At the peak of violence between March and May 2024, hospitals, stores, and schools either closed or became largely inaccessible, while most people who lived in safer areas avoided leaving their homes. Moving around the capital became almost impossible, with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Designated Expert on Haiti, William O’Neill, declaring: ‘The fear is palpable in people’s eyes and in their voices. The capital is almost entirely controlled and surrounded by gangs, making Port-au-Prince a large open-air prison’.17OHCHR, ‘Restoring dignity: A global call to end the violence in Haiti’. Between 3 March and 20 May 2024, gangs forced the closure of Toussaint Louverture International Airport, placing the country under almost total lockdown and preventing the then Prime Minister of Haiti, Ariel Henry, from returning to the country.18D. Coto (Associated Press), ‘Haiti’s main airport reopens nearly 3 months after gang violence forced it closed’, The Hill, 20 May 2024.

Following the coalition’s blockade of the capital’s main shipping ports, prices of fuel, food, and other essentials soared. The World Food Programme (WFP) registered a twenty-seven per cent increase in the cost of a standard food basket in the course of 2024, leaving millions of Haitians unable to afford basic meals. As violence escalated and major infrastructure shut down, growing numbers of people turned to black markets, where fuel was selling for up to fifty per cent over official prices.19Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC), ‘Viv Ansanm: How a gang coalition has transformed violence in Port-au-Prince’, Risk Bulletin No 1, July 2024.

The humanitarian fallout has also been massive: the UN International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that internal displacement rose sharply from 362,000 people in March to more than 578,000 in June 2024,20IOM, ‘Haiti – Key information on the internal displacement situation in Haiti – Round 7 (June 2024)’, 9 June 2024. before climbing to almost 1.3 million for the country as a whole by June 2025 – almost one in ten of the total population. Gang violence had provoked a twenty-four per cent increase in the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in only six months following December 2024.

A Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission started deployment in June 2024 following UN Security Council authorization the previous October.21UN Security Council Resolution 2699, adopted on 2 October 2023 by thirteen votes to nil with two abstentions (China and Russia), operative para 1. The MSS, which had a mandate through to 2 October 2025, had reached 1,000 personnel by the beginning of the year. Troops came from the Bahamas, Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, and Kenya, which led the mission. But the total was less than half of the 2,500 personnel that were planned.22M. Besheer, ‘UN chief rules out UN peacekeepers for Haiti’, Voice of America, 25 February 2025.

In late September 2025, the UN Security Council authorized Member States to transition the MSS mission to a ‘Gang Suppression Force’, for an initial period of twelve months.23UN Security Council Resolution 2793, adopted on 30 September 2025 by twelve votes to nil with three abstentions (China, Pakistan, and Russia), operative para 1. The resolution authorized Member States participating in the Gang Suppression Force (GSF), ‘in strict compliance with international law, including international human rights law’ to ‘neutralize, isolate, and deter gangs that continue to threaten the civilian population, abuse human rights and undermine Haitian institutions’. They were also tasked with providing security for critical infrastructure sites ‘together and in coordination with’ the PNH ‘and the Haitian armed forces’.24Ibid, operative para 1(a) and (b).

The GSF was expected to become operational in the first half of 2026.25J. Charles, ‘Special representative named for U.S. backed-Gang Suppression Force in Haiti’, Miami Herald, 2 December 2025. The GSF will rely on operational and logistical support from a UN Support Office in Haiti (UNSOH) that was still to be set up in Port-au-Prince as of December 2025. This will be support the MSS did not receive. UNSOH will provide fuel, water, accommodation, and other necessary infrastructure for the GSF bases, as well as medical and mobility support.26Mohor, ‘Haiti in-depth: The new Gang Suppression Force and what it means for Haitians’.

Conflict Classification and Applicable law

There was one NIAC in Haiti during the review period:

Haiti (supported by the MSS) v Viv Ansanm coalition.

This armed conflict is regulated by Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and customary international humanitarian law (IHL). Haiti is also a State Party to Additional Protocol II of 1977.27Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978. The NIAC in Haiti meets the additional requirements of Article 1(1) of Additional Protocol II – in particular, that the organized armed group exercise a level of territorial control that would enable it to sustain military operations and implement the Protocol – and thus the Protocol is directly applicable to the conflict.

According to the United Nations, twenty-three gangs operate in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area (other estimates go as high as 200 armed groups for the whole of Haiti).28UN, ‘En Haïti, les gangs ont plus de puissance de feu que la police’, Press release, 6 April 2024. Beyond the capital, gang violence has spread to provincial areas such as Arcahaie, Gonaïves, Petite Rivière de l’Artibonite, and Verrettes.29OHCHR, ‘La violence des groupes criminels s’étend en dehors de Port-au-Prince la situation du Bas-Artibonite de janvier 2022 à octobre 2023’, Report, November 2023. Provincial gangs such as ‘400 Mawozo’, ‘Chen Mechan’, and ‘Kokorat san ras’ have established control over swathes of territory, engaging in systematic kidnapping and killing of civilians, and forcing the displacement of local populations.30J.-B. Jean, ‘Gonaïves: le gang Kokorat san ras continue de kidnapper et de tuer’, Le Nouvelliste, 25 July 2023; Agence France-Presse, ‘Plus de 700 000 déplacés internes en Haïti’, Le Devoir, 2 October 2024. The groups control strategic routes linking Port-au-Prince to ports and land borders, effectively fragmenting the country.

In some instances outside the Viv Ansanm coalition, an armed group engaged in violence does not meet the IHL requirement of ‘organization’. In other cases, it is the issue of intensity and regularity of violence that is at issue. In particular, while Gran Grif controls much of the northern Artibonite department of Haiti, it was not party to a separate NIAC with the authorities during the reporting period. Its multiple acts of deadly violence, which include an infamous massacre in Port-Sondé in October 2024, were not such as to engage the application of IHL.

Haiti is a signatory but not a State Party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court,31Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002 (hereafter, ICC Statute). as it has still to ratify the treaty. Therefore, the acts described in this report do not fall within the jurisdiction of the Court, and will not do so unless either the situation is referred to the Court by the UN Security Council, or Haiti makes the requisite declaration under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

The period under review saw serious violations by Viv Ansanm of the protection afforded by IHL to civilians and civilian infrastructure across Haiti, but especially in the capital. The civilian population in general continued to be regularly attacked by the coalition with violence characterized by deliberate shooting and stabbing of civilians, systematic use of sexual violence, widespread destruction of civilian infrastructure, and several instances of mass killings.

These are not only war crimes but may also amount to crimes against humanity – defined under international criminal law as a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population.32Art 7(1), ICC Statute. In this regard, UN officials and experts reported the ‘deliberate, systematic and pervasive use of sexual violence, including collective rape and mutilation, by gangs as a means of exerting territorial control and to punish communities.’33Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Haiti’, Country Profile, 15 July 2025.

Civilian Objects under Attack

Under customary IHL, attacks may only be directed against military objectives. Attacks must not be directed against civilian objects.34ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives35ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. and, as such, are protected against attack.36ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 10: ‘Civilian Objects’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.37ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

Attacks against health facilities

The health infrastructure in Haiti, already fragile before the escalation of gang violence, suffered serious damage during the reporting period. By July 2025, only one third of health facilities in Port-au-Prince remained fully functional. Criminal gangs ‘burned, ransacked and destroyed many hospitals and clinics, forcing many to close or suspend their operations’, Mr O’Neill told the UN Human Rights Council.38UN, ‘Haiti gangs crisis: Top rights expert decries attacks on hospitals’, Press release, 3 January 2025. Medical personnel were not spared from violence: gangs ‘murdered and kidnapped physicians, nurses and healthcare workers, including humanitarian workers’.39Ibid.

Among many attacks, on 17 December 2024, Viv Ansanm attacked the Bernard Mevs General Hospital in Port-au-Prince.40L. Rocha and J. Lukiv, ‘Three shot dead as gunmen attack Haiti hospital’, BBC News, 25 December 2024. The violence against health facilities reached a symbolic nadir a week later, when three journalists and a police officer were killed at the hospital during its official reopening ceremony.41‘Two reporters and a police officer killed in shooting at Haiti hospital reopening’, The Guardian, 25 December 2024. Inevitably, the targeting of health facilities had cascading effects on access to medical care, with deep and persistent barriers to receiving emergency care, maternal health services, treatment for chronic conditions, and trauma care – the latter particularly critical given the scale of gunshot and knife wounds being inflicted on the population.42MSF, ‘People and the health system are trapped in escalating violence in Haiti’, Press release, 3 October 2025.

Attacks against transportation infrastructure

Transportation infrastructure became a primary target for attacks by Viv Ansanm, with devastating consequences for humanitarian access, economic activity, and civilian movement. The most significant attacks focused on Toussaint Louverture Airport, with gang members attempting to seize control of the facility on 4 March 2024, exchanging gunfire with police and the Haitian Armed Forces.43Associated Press, ‘Gangs in Haiti try to seize control of main airport in newest attack on government sites’, Politico, 4 March 2024. The assault forced the airport to close for nearly three months, with all commercial flights suspended,44International Crisis Group ‘Locked in Transition: Politics and Violence in Haiti’, Report No 107, 19 February 2025. part of the gangs’ broader strategy to block travel and isolate Haiti from international support.45Associated Press, ‘Haiti’s main airport shuts down as gang violence surges and a new prime minister is sworn in’, Manila Bulletin, 12 November 2024.

The violence against aircraft escalated further on 11 November 2024, when gang members opened fire on three commercial aircraft. Spirit Airlines Flight 951 from Fort Lauderdale was struck by gunfire multiple times while attempting to land.46Associated Press, ‘Spirit Airlines flight hit by gunfire as gang violence shuts down Haiti’s main airport’, CBC, 12 November 2024. A JetBlue Airways flight from Haiti to New York and an American Airlines plane were similarly targeted.47Associated Press, ‘Haiti’s main airport shuts down as gang violence surges and a new prime minister is sworn in’. The attacks forced the immediate and indefinite closure of the airport, initially until 18 November, but with subsequent extensions. These coordinated attacks severely constrained humanitarian access at a critical moment.48Associated Press, ‘U.S. prohibits airlines from flying to Haiti after planes were shot by gangs’, NPR, 13 November 2024.

In addition to its attacks on aircraft and the airport, Viv Ansanm also targeted maritime and road infrastructure. Beginning in March 2024 and continuing throughout the reporting period, the coalition blockaded Port-au-Prince’s main seaport, strangling the flow of goods into the capital and contributing directly to the dramatic increase in food and fuel prices.49UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

Attacks against schools

The education system in Haiti suffered catastrophic damage during the reporting period, with profound implications for an entire generation of children. In January 2025 alone, armed groups struck 47 schools in Port-au-Prince, coming on top of the 284 they destroyed in 2024. Thus, according to UNICEF, a total of 331 educational facilities were devastated in a little over a year.50UN, ‘Haiti: Massive surge in child armed group recruitment, warns UNICEF’, UN News, 28 February 2025. Viv Ansanm was identified as having vandalized and set fire to many educational buildings between February and May 2024, including university faculties and schools across Port-au-Prince.51UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

The deliberate destruction of schools was a systematic assault on the education system. Its cumulative effects are such that 1.2 million children in Haiti have been deprived of education during the reporting period, primarily as a result of the attacks on students and schools.52Human Rights Watch, ‘Haiti’, Country Chapter, 2025. Only one in five schools in Port-au-Prince remained open and operational at normal capacity by October 2024.53UNICEF, ‘Haiti’, Humanitarian Situation Report No 9, October 2024.

Attacks against media and communications infrastructure

Media outlets and journalists also faced systematic targeting during the reporting period, with gang attacks reaching a crescendo in March 2025 when three major media institutions were destroyed in the span of four days. The attacks appeared coordinated and were all attributed to Viv Ansanm.

On the night of 12–13 March 2025, armed individuals deliberately set fire to Radio Télévision Caraïbes (RTVC) in downtown Port-au-Prince.54Thomson Reuters, ‘Haiti gangs set fire to building once home to nation’s oldest radio station’, KFGO, 13 March 2025. The station, Haiti’s oldest radio broadcaster, had relocated to Pétion-Ville the previous year for security reasons, but its historic headquarters – a symbol of Haitian media heritage – was destroyed. The following day, 13 March, the headquarters of Radio Mélodie FM was stormed by Viv Ansanm fighters and suffered major damage before being set ablaze.55EEPA, ‘Viv Ansanm attacks force evacuations and target media; Escalating violence displaces 60,000; CPT president pledges security reforms amid election delays’, 19 March 2025.

On 15 March, heavily armed members of Viv Ansanm attacked Télé Pluriel, a privately owned television station in the Delmas 19 neighbourhood. The station was ransacked, with equipment stripped and looted, before the building was set on fire.56Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), ‘Haitian gangs set fire to 3 Port-au-Prince radio stations as violence escalates’, 20 March 2025. Gangs also attacked other businesses in the area, including the R&C Plaza.57CPJ, ‘Haitian gang takes over radio station, renames it Taliban FM’, 25 April 2025.

These attacks on media infrastructure occurred in parallel with direct threats against individual journalists. In October 2024, Jimmy Chérizier released a video calling on his associate Vitelhomme Innocent to capture specific journalists and bring them before him for ‘judgment’.58J.-J. Celestin, ‘Des journalistes menacés par des gangs: l’AJH et SOS Journalistes dénoncent et appellent à l’action’, Le Nouvelliste, 19 March 2024. He named four by name: Johnny Ferdinand and Guerrier Dieuseul of Radio Caraïbes; Luckner Désir (alias ‘Lucko’); and Ésaïe César of Télé Éclair. He added that he was seeking other journalists whose names he had not yet revealed. The Association des Journalistes Haïtiens (AJH) and SOS Journalistes issued statements on 22 October condemning the threats and calling for immediate protective measures.59Ibid. None was forthcoming.

Attacks against homes and residential areas

Viv Ansanm launched numerous large-scale attacks on residential areas during the reporting period, often involving arson, looting, and forced displacement. The attacks were characterized by their indiscriminate nature and apparent objective of terrorizing populations and establishing territorial control. Attacks aimed at spreading terror among the civilian population are strictly prohibited under IHL and can amount to war crimes.60ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 2: ‘Violence Aimed at Spreading Terror among the Civilian Population’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

The pattern of residential violence had already been escalating in the months immediately preceding the current reporting period. Between January and July 2024, the security situation in Carrefour and Gressier communes collapsed, with gang members operating openly in streets, markets, sports clubs, and bus stations, conducting sporadic raids, and engaging in widespread killing, rape, kidnapping, theft, and extortion.61Réseau National de Défense des Droits Humains (RNDDH), ‘Rapport: Carrefour-Gressier, 15 août 2024’, Report, 15 August 2024. In the Rivière Froide area of these communes, gangs broke into houses specifically searching for women and girls, whom they abducted and took away to abuse over the course of several days.62Ibid.

On 24 March 2024, Viv Ansanm launched a large-scale attack on blocks around the National Palace in Port-au-Prince. The assault, in which the 5 Segonn gang under Johnson ‘Izo’ André was identified as the main assailant, sought to empty the area of population and cause maximum damage, according to a UN Security Council sanctions listing for Viv Ansanm.63UN Security Council, Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing. Since then, the violence has intensified and spread. On 6 August 2024, two gangs that are part of Viv Ansanm 5 Segonn and Canaan killed at least ten people and burned numerous houses during attacks against the Arcahaïe and Cabaret communes in the northern areas of the capital. The assault was an attempt to extend coalition control along the Port-au-Prince bay area.64Council of the European Union, ‘Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/1576 of 29 July 2025 implementing Article 17 (1) of Regulation (EU) 2022/2370 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Haiti’, 29 July 2025.

The situation in Carrefour and Gressier also worsened. Gangs occupied these communes, using ‘extreme brutality to bring residents under their control’.65‘Haiti’s gangs inflict ‘extreme brutality’ as casualties rise – UN report’, Al Jazeera, 30 October 2024. The 103 Zombies and Ti Bois gang, operating along with the Grand Ravine – all members of the Viv Ansanm coalition – shot ‘wildly’ at civilians and ‘judged’ and executed those who refused to submit to their rule.66UN Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH), ‘Quarterly Report on the Human Rights Situation in Haiti’, October–December 2024’. Between October and December 2024 alone, at least 163 people were killed or seriously injured by gang members in the neighbourhoods of Fontamara, La Colline, Mariani, Rivière Froide, and Thor.67Ibid. One of the most serious incidents occurred on 29 November 2024 in the Ka Miyay neighbourhood (Carrefour). The 103 Zombies and Ti Bois gangs attacked the homes of relatives of a self-defence group from neighbouring Pedro (Léogâne), killing at least fifty. Some were executed in the street in front of their homes, while others were murdered inside.68Ibid.

Between 11 and 19 November 2024, gangs belonging to Viv Ansanm attacked several locations in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince, including Nazon, Pernier, and Vivy Mitchel, in an attempt to invade Delmas and Pétionville.69Council of the European Union, ‘Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/1576 of 29 July 2025’. The resulting violence killed at least 220 people, injured 92, and displaced nearly 41,000.70Ibid. In late January 2025, the coalition conducted a series of coordinated assaults on Kenscoff (West Department), located south of Port-au-Prince. The attacks sought to establish gang control over the area and gain access to routes leading to the south-east of the country. The violence killed up to 150 people, destroyed 100 homes, and caused 3,139 residents to flee.71Ibid.

The scale of residential attacks reached a new peak in late March 2025. On the night of 30–31 March, between 2 and 3 am, members of the 400 Mawozo and Talibans de Canaan gangs – both members of Viv Ansanm – attacked the city of Mirebalais in the Centre department, entering through Trianon in the 2nd communal section of Grand-Boucan.72RNDDH, ‘Chute de deux communes du département du Centre aux mains des bandits armés: Les authorities de la transition aggravent la situation sécuritaire du pays’, Report, 10 April 2025. They burnt many houses and several vehicles. Although local self-defence brigades (nicknamed ‘Bakòp Feray’), agents of the Brigade de Sécurité des Aires Protégées (BSAP), and PNH officers initially resisted, repeated calls for reinforcement went unanswered. Around 8 am their resistance weakened and the gangs penetrated the city. Police officers posted at the Mirebalais Commissariat and Civil Prison fled, allowing gang members to set fire to the police station and seize control of the prison, where they orchestrated the escape of all the inmates. The attackers then set fire to buildings, private houses, and – significantly for civilian livelihoods – the Mirebalais market.73Ibid.

Civilians under Attack

Under customary IHL, civilians enjoy general protection from the effects of hostilities, unless and for such time as they directly participate in hostilities.74ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Accordingly, parties to armed conflicts must at all times distinguish between combatants and civilians, and are prohibited from directing attacks against civilians.75ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants’. Civilians may be incidentally affected by attacks against lawful military objectives. However, such attacks must not be disproportionate, and the attacker must take all feasible precautions to avoid, or at the least to minimize, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, and damage to civilian objects.76ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’; and Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’.

Attacks directed against civilians

During the reporting period, multiple large-scale attacks resulted in high civilian death tolls. The most significant incident that took place in the context of and was associated with the NIAC with the Viv Ansanm coalition was the Wharf Jérémie massacre on 6–7 December 2024. A second massacre, which occurred in Port-Sondé in October 2024, did not fall within the context of an armed conflict as the acts of the perpetrator, the Gran Grif gang,77The United Nations and the United States treat Gran Grif and Viv Ansanm as separate entities. ‘Trump administration plans to designate Haitian gangs as foreign terrorist groups’, France 24, 29 April 2025; European Union Council Decision (CFSP) 2025/1575 of 29 July 2025, amending Decision (CFSP) 2022/2319 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Haiti. did not reach the regularity and intensity required by IHL.

Wharf Jérémie is a neighbourhood of Cité Soleil in Port-au-Prince. Micanor Altès (also known as Wa Mikanò and Monel Felix), leads the Wharf Jérémie gang, which is a member of Viv Ansanm. In the course of the attack, the group murdered perhaps as many as 207 people (although the Haitian authorities later revised this figure down to 184).78UN, ‘Over 207 executed in Port-au-Prince massacre: UN report’, UN News, 23 December 2024; OHCHR, ‘Restoring dignity: A global call to end the violence in Haiti’, Story, 7 April 2025; J. Charles, ‘Haiti gang leader blames witchcraft for his son’s death, kills more than 100 people’, Miami Herald, 9 December 2024. Victims included men, women, and children – the youngest victim being three months old. Many victims were older persons between sixty and eighty years of age. Gang members specifically targeted persons it suspected of practicing Vodou and older persons accused of witchcraft.79UN, ‘Over 207 executed in Port-au-Prince massacre: UN report’, UN News, 23 December 2024. The bodies of many of the victims were mutilated and burned.80OHCHR, ‘Haiti: Over 5,600 killed in gang violence in 2024, UN figures show’. Micanor Altès is said to have ordered the massacre to punish those he suspected of having used witchcraft to harm his child.81W. Mérancourt and M. Hay Brown, ‘In Haiti, gangs massacre worshipers at a Vodou temple’, The Washington Post, 9 December 2024.

The Pont-Sondé massacre, another deadly incident in Haiti’s recent memory, was perpetrated by the Gran Grif gang.82S. Pellegrini, ‘Pont-Sondé Massacre Marks a Surge in Gran Grif’s Deadly Campaign in Artibonite – ACLED Insight’, Report, 11 April 2024. Led by Luckson Elan, who has been listed by the UN Security Council sanctions committee on Haiti,83UN Security Council, ‘Luckson Elan’, Haiti Sanctions List, 27 September 2024. the Gran Grif gang controls significant areas across the Artibonite department in central Haiti. During Saint-Michel festival celebrations of 3 October 2024, at least seventy civilians (and possibly more than twice as many) were killed. Most of the victims – men, women, and children – were asleep when they were attacked. Gang members used firearms and machetes to kill and wound, with some victims burned alive in their homes. Many women and girls were raped during the assault. Forty-five houses were reportedly set ablaze.84‘At least 70 people killed in gang attack on Haitian town: UN’, Al Jazeera, 4 October 2024.

That massacre was not regulated by IHL. But another series of assaults at the end of November 2024 in the central department, which again involved the murder of men, women, and children, and the burning of homes, indicated that Gran Grif might become party to a NIAC with the Haitian authorities in the future. Indeed, the United Nations said that killings had risen dramatically in Artibonite in the course of 2025, with 1,303 victims reported in the central regions of Haiti between January and August, compared with 419 during the same period in 2024. ‘I heard heavy shooting, so much shooting’, one unnamed man told Associated Press. He criticized the lack of police, asking: ‘Why don’t they send any drones to Artibonite? They just use the drones in Port-au-Prince. I feel this gang is special. They don’t want to destroy this gang.’85Associated Press, ‘Gangs launch large-scale attack in Haiti’s central region as hundreds flee gunfire and burning homes’, CNN, 1 December 2025. Under the law of law enforcement, drone strikes may only be necessary where strictly unavoidable to protect life.86Basic Principle 9, UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials; adopted at Havana, 7 September 1990. In December 1990, the UN General Assembly welcomed the Basic Principles and invited governments to respect them. UN General Assembly Resolution 45/166, adopted without a vote on 18 December 1990, para 4.

Attacks on humanitarian aid

The systematic blockade of ports and attacks on transportation infrastructure by Viv Ansanm had far-reaching consequences for food security across Haiti. Beginning in March 2024, Viv Ansanm blockaded Port-au-Prince’s main seaport, strangling the flow of goods into the capital and surrounding areas.87GITOC, ‘Viv Ansanm: How a gang coalition has transformed violence in Port-au-Prince’. With ordinary supply chains disrupted, civilians increasingly turned to illegal markets, forced to pay significantly higher prices.88WFP, ‘What’s Happening in Haiti? Explainer on Gang Violence, Hunger Crisis and Humanitarian Aid to Civilians’, 28 June 2024.

The economic warfare waged through infrastructure control extended beyond ports. As mentioned above, Viv Ansanm’s attacks on Toussaint Louverture Airport in March 2024 forced its closure, preventing the delivery of humanitarian supplies.89UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing. Viv Ansanm members blocked roadways linking Port-au-Prince to ports and land borders, further restricting the transportation of vital supplies and the movement of humanitarian personnel.90UN, ‘Haïti: la moitié de la population confrontée à une faim aiguë’, UN News, 20 September 2024. Since late February 2024, Viv Ansanm members have attacked critical infrastructure, robbed containers carrying first-aid supplies, and looted hospitals and pharmacies, particularly in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area.91UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

The combined effect of these restrictions has been to weaponize hunger and economic deprivation. Families who had already lost income due to insecurity and business closures increasingly struggled to afford to buy food. Markets became dangerous places with gang members routinely present and the threat of violence or extortion deterring both vendors and customers. The destruction of the Mirebalais market during the 30–31 March 2025 attack represented not merely property damage but elimination of a vital source of food for the local population. The impact on children was particularly severe. With schools closed and displacement widespread, many families lost access to school feeding programmes that had provided the children with critical nutrition.92WFP, ‘Haïti au bord du gouffre: le PAM intensifie ses efforts alors que la violence alimente les déplacements et la faim’, 2 December 2024.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

Customary and treaty IHL provides fundamental guarantees for anyone in the power of a party to a conflict, prohibiting acts such as torture, inhumane or degrading treatment, collective punishments, sexual violence, enforced disappearance, and unfair trials. Special protection is afforded to civilians who face a specific risk of harm, such as women, children, refugees, and IDPs.93ICRC, Customary IHL Rules 134–138: ‘Chapter 39. Other Persons Afforded Specific Protection’.

Conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence

Rape and other forms of sexual and gender-based violence in connection with armed conflict are prohibited and constitute serious violations of IHL.94ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. Sexual violence reached epidemic proportions in Haiti during the reporting period, perpetrated systematically by gangs as a means of exerting territorial control and punishing communities.95Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Haiti’, Country Profile, 15 July 2025; and ‘Open Letter to the Haitian Transitional Government Demanding Action on Gender-Based Violence’, 20 February 2025. The scale and deliberate nature of sexual violence represents another disturbing feature of the conflict, with UNICEF describing it as a ‘weapon of war’.96R. Opota and H. Cadet, ‘Silent Crisis: The Long Healing Process of Survivors of Sexual Violence in Haiti’, Online article, UNICEF, 26 June 2025; Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, ‘Haiti: Sexual and gender-based violence, including acts perpetrated by criminal groups’, Query Response HTI201783.E, 5 February 2024; Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), ‘Haiti’, Public Health Situation Analysis, 4 October 2024.

Grassroots and international organizations documented an alarming rise in reported rapes between April and June 2024, particularly in the municipalities of Carrefour, Cité Soleil, Croix-des-Bouquets, Delmas, Gressier, and Port-au-Prince. Some health facilities were receiving up to forty rape victims a day during peak periods.97Human Rights Watch, ‘Haiti: Scarce Protection as Sexual Violence Escalates’, 25 November 2024. In displacement sites too, sexual violence became endemic. During the first quarter of 2024 alone, at least 216 cases were documented in displacement sites in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area.98Global Protection Cluster, ‘Protection des personnes déplacées internes en Haïti’, Advocacy Brief, May 2024. Risk factors contributing to sexual violence in displacement settings included lack of space, inadequate lighting, and absence of separate latrines and bathing areas for men and women.99Global Protection Cluster, ‘Haiti’, Protection Analysis Update, September 2025. Women and children were the primary victims.

In a statement on 7 February 2025, UNICEF spokesperson James Elder described a ‘staggering 1,000-percent increase in sexual violence against children in Haiti’, declaring that it had ‘turned their bodies into battlegrounds’.100UNICEF, ‘Haiti’s children under siege: The staggering rise of child abuse and recruitment by armed groups’, Press Release, 7 February 2025. More than one quarter of reported cases involved gang rapes, according to the UN Secretary-General.101UN, ‘Secretary-General’s remarks to the Security Council – on Haiti’, Statement, 28 August 2025. Elder stated that ‘armed groups inflict unimaginable horrors on children’, and that ‘children are being used by armed gangs in Haiti’. The testimony of survivors confirms the systematic and calculated nature of the violence. ‘Rosaline’ (not her real name), a 16-year-old girl, was abducted by armed men and placed in a van with other young girls.102Agence France-Presse, ‘Sexual Violence Against Children Soars in Haiti: UN’, Barron’s, 7 February 2025. She was taken to a warehouse where she was extensively beaten and drugged. Over a period she believes was about one month, she was persistently raped.103Ibid. Only when the armed group realized no one could pay her ransom did they release her.104Amnesty International, ‘Gang’s assault on childhood in Haiti’, Report, 12 February 2025.

Adult women also suffered horrific violence. ‘Ellie M’, a 29-year-old survivor, was abducted and gang-raped for five hours by armed members of G9 (a Viv Ansanm member). ‘Afterward, they shot me in the foot’, she told Human Rights Watch. She was infected with HIV and became pregnant as a result of the assault.105Human Rights Watch, ‘Haiti: Scarce Protection as Sexual Violence Escalates’, Report, 25 November 2024. A pattern of sexual violence in mass killings occurred on multiple occasions during the reporting period.

Child protection

Under IHL, children are afforded special protection in armed conflicts, recognizing their particular vulnerability. Core rules prohibit the recruitment and use of children under the age of fifteen years in hostilities, whether in State armed forces or non-State armed groups, and forbid their participation in combat.106ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 136: ‘Recruitment of Child Soldiers’. Children are entitled to general protection as civilians, including against direct attack, arbitrary detention, sexual violence, and ill-treatment, as well as specific guarantees such as access to food, medical care, and education. If detained, they must be held separately from adults (unless they are with their family) and treated in a manner appropriate to their age. Evacuation and reunification of separated children with their families are also prioritized.107ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 135: ‘Children’.

Yet, the UN Secretary-General has reported that, for 2024, the number of grave violations against children that the organization verified in Haiti (2,269) was among the world’s highest. Moreover, in terms of the percentage increases in the number of violations compared to 2023, Haiti, at 490 per cent, was the third highest in the world.108‘Children and armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 7.

The recruitment and use of children by armed groups has similarly escalated sharply, with the UN reporting a seventy per cent surge in child recruitment in Haiti between the middle of 2023 and the middle of 2024.109‘Haiti: Child recruitment by armed groups surges 70 per cent’, UN News, 24 November 2024. According to UNICEF, children now comprise as many as half of all armed group members, with some as young as eight years of age. Many are abducted or coerced, while others join in search of food, protection, or a sense of belonging amid widespread poverty and insecurity.

An estimated one million children now live in areas controlled or influenced by gangs, according to Amnesty International. In interviews with eleven boys and three girls, the organization documented how children are exploited for surveillance, deliveries, and domestic labour, and in some cases forced to participate in attacks. Girls are particularly vulnerable, often compelled to act as ‘wives’ for gang members and subjected to relentless sexual abuse.110Amnesty International, ‘Gangs’ assault on childhood in Haiti’. A UNICEF spokesperson described the situation as a ‘lethal cycle’, where children are drawn into the very violence that destroys their communities.111UNICEF, ‘Haiti’s children under siege: The staggering rise of child abuse and recruitment by armed groups’.

- 1OHCHR, ‘Haiti: Over 5,600 killed in gang violence in 2024, UN figures show’, Press release, 7 January 2025.

- 2OHCHR, ‘Restoring dignity: A global call to end the violence in Haiti’, News release, 7 April 2025.

- 3OHCHR, ‘Haiti: UN Human Rights Chief alarmed by widening violence as gangs expand reach’, Press release, 13 June 2025.

- 4F. Robles, ‘Massacre in Haiti’s Capital Leaves Nearly 200 Dead, U.N. Says’, The New York Times, 8 December 2024.

- 5UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions list, July 2025.

- 6‘Assessment of progress achieved on the key benchmarks pursuant to paragraph 25 of resolution 2700 (2023), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/711, 1 October 2024, para 3.

- 7S. Pelligrini, ‘Viv Ansanm: Living together, fighting united – the alliance reshaping Haiti’s gangland’, Report, ACLED, 16 October 2024.

- 8‘From criminal governance to community fragmentation: Addressing Haiti’s escalating crisis’, Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, Policy Brief, Geneva, September 2025, p 14.

- 9‘Viv Ansanm: Comment une coalition de gangs a transformé la violence à Port-au-Prince’, Risk Bulletin No 1, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, July 2024.

- 10K. Ives, ‘As Cops Target Lower Delmas, Viv Ansanm Leaders Declare that Haitians are Free to Move around Haiti Again’, Haïti Liberté, 27 November 2024.

- 11‘1er Janvier 2025: Le groupe criminel “Viv Ansanm” désormais un parti politique’, Kominotek, 3 January 2025.

- 12UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions list.

- 13Y. Yacou, ‘Les États-Unis et l’ONU sanctionnent deux figures clés du crime organisé en Haïti’, Franceinfo, 22 October 2025.

- 14

- 15D. Mohor, ‘Haiti in-depth: The new Gang Suppression Force and what it means for Haitians’, The New Humanitarian, 3 December 2025.

- 16International Criminal Court, Prosecutor v Bosco Ntaganda, Judgment (Trial Chamber) (Case No ICC-01/04-02/06), 8 July 2019, para 716.

- 17OHCHR, ‘Restoring dignity: A global call to end the violence in Haiti’.

- 18D. Coto (Associated Press), ‘Haiti’s main airport reopens nearly 3 months after gang violence forced it closed’, The Hill, 20 May 2024.

- 19Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC), ‘Viv Ansanm: How a gang coalition has transformed violence in Port-au-Prince’, Risk Bulletin No 1, July 2024.

- 20

- 21UN Security Council Resolution 2699, adopted on 2 October 2023 by thirteen votes to nil with two abstentions (China and Russia), operative para 1.

- 22M. Besheer, ‘UN chief rules out UN peacekeepers for Haiti’, Voice of America, 25 February 2025.

- 23UN Security Council Resolution 2793, adopted on 30 September 2025 by twelve votes to nil with three abstentions (China, Pakistan, and Russia), operative para 1.

- 24Ibid, operative para 1(a) and (b).

- 25J. Charles, ‘Special representative named for U.S. backed-Gang Suppression Force in Haiti’, Miami Herald, 2 December 2025.

- 26Mohor, ‘Haiti in-depth: The new Gang Suppression Force and what it means for Haitians’.

- 27Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978.

- 28UN, ‘En Haïti, les gangs ont plus de puissance de feu que la police’, Press release, 6 April 2024.

- 29

- 30J.-B. Jean, ‘Gonaïves: le gang Kokorat san ras continue de kidnapper et de tuer’, Le Nouvelliste, 25 July 2023; Agence France-Presse, ‘Plus de 700 000 déplacés internes en Haïti’, Le Devoir, 2 October 2024.

- 31Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002 (hereafter, ICC Statute).

- 32Art 7(1), ICC Statute.

- 33Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Haiti’, Country Profile, 15 July 2025.

- 34ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 35

- 36

- 37ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

- 38UN, ‘Haiti gangs crisis: Top rights expert decries attacks on hospitals’, Press release, 3 January 2025.

- 39Ibid.

- 40L. Rocha and J. Lukiv, ‘Three shot dead as gunmen attack Haiti hospital’, BBC News, 25 December 2024.

- 41‘Two reporters and a police officer killed in shooting at Haiti hospital reopening’, The Guardian, 25 December 2024.

- 42MSF, ‘People and the health system are trapped in escalating violence in Haiti’, Press release, 3 October 2025.

- 43Associated Press, ‘Gangs in Haiti try to seize control of main airport in newest attack on government sites’, Politico, 4 March 2024.

- 44International Crisis Group ‘Locked in Transition: Politics and Violence in Haiti’, Report No 107, 19 February 2025.

- 45Associated Press, ‘Haiti’s main airport shuts down as gang violence surges and a new prime minister is sworn in’, Manila Bulletin, 12 November 2024.

- 46Associated Press, ‘Spirit Airlines flight hit by gunfire as gang violence shuts down Haiti’s main airport’, CBC, 12 November 2024.

- 47Associated Press, ‘Haiti’s main airport shuts down as gang violence surges and a new prime minister is sworn in’.

- 48Associated Press, ‘U.S. prohibits airlines from flying to Haiti after planes were shot by gangs’, NPR, 13 November 2024.

- 49UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

- 50UN, ‘Haiti: Massive surge in child armed group recruitment, warns UNICEF’, UN News, 28 February 2025.

- 51UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

- 52Human Rights Watch, ‘Haiti’, Country Chapter, 2025.

- 53UNICEF, ‘Haiti’, Humanitarian Situation Report No 9, October 2024.

- 54Thomson Reuters, ‘Haiti gangs set fire to building once home to nation’s oldest radio station’, KFGO, 13 March 2025.

- 55

- 56Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), ‘Haitian gangs set fire to 3 Port-au-Prince radio stations as violence escalates’, 20 March 2025.

- 57CPJ, ‘Haitian gang takes over radio station, renames it Taliban FM’, 25 April 2025.

- 58J.-J. Celestin, ‘Des journalistes menacés par des gangs: l’AJH et SOS Journalistes dénoncent et appellent à l’action’, Le Nouvelliste, 19 March 2024.

- 59Ibid.

- 60ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 2: ‘Violence Aimed at Spreading Terror among the Civilian Population’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 61Réseau National de Défense des Droits Humains (RNDDH), ‘Rapport: Carrefour-Gressier, 15 août 2024’, Report, 15 August 2024.

- 62Ibid.

- 63UN Security Council, Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

- 64

- 65‘Haiti’s gangs inflict ‘extreme brutality’ as casualties rise – UN report’, Al Jazeera, 30 October 2024.

- 66UN Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH), ‘Quarterly Report on the Human Rights Situation in Haiti’, October–December 2024’.

- 67Ibid.

- 68Ibid.

- 69Council of the European Union, ‘Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/1576 of 29 July 2025’.

- 70Ibid.

- 71Ibid.

- 72

- 73Ibid.

- 74

- 75

- 76ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’; and Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’.

- 77The United Nations and the United States treat Gran Grif and Viv Ansanm as separate entities. ‘Trump administration plans to designate Haitian gangs as foreign terrorist groups’, France 24, 29 April 2025; European Union Council Decision (CFSP) 2025/1575 of 29 July 2025, amending Decision (CFSP) 2022/2319 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Haiti.

- 78UN, ‘Over 207 executed in Port-au-Prince massacre: UN report’, UN News, 23 December 2024; OHCHR, ‘Restoring dignity: A global call to end the violence in Haiti’, Story, 7 April 2025; J. Charles, ‘Haiti gang leader blames witchcraft for his son’s death, kills more than 100 people’, Miami Herald, 9 December 2024.

- 79UN, ‘Over 207 executed in Port-au-Prince massacre: UN report’, UN News, 23 December 2024.

- 80OHCHR, ‘Haiti: Over 5,600 killed in gang violence in 2024, UN figures show’.

- 81W. Mérancourt and M. Hay Brown, ‘In Haiti, gangs massacre worshipers at a Vodou temple’, The Washington Post, 9 December 2024.

- 82S. Pellegrini, ‘Pont-Sondé Massacre Marks a Surge in Gran Grif’s Deadly Campaign in Artibonite – ACLED Insight’, Report, 11 April 2024.

- 83UN Security Council, ‘Luckson Elan’, Haiti Sanctions List, 27 September 2024.

- 84‘At least 70 people killed in gang attack on Haitian town: UN’, Al Jazeera, 4 October 2024.

- 85Associated Press, ‘Gangs launch large-scale attack in Haiti’s central region as hundreds flee gunfire and burning homes’, CNN, 1 December 2025.

- 86Basic Principle 9, UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials; adopted at Havana, 7 September 1990. In December 1990, the UN General Assembly welcomed the Basic Principles and invited governments to respect them. UN General Assembly Resolution 45/166, adopted without a vote on 18 December 1990, para 4.

- 87GITOC, ‘Viv Ansanm: How a gang coalition has transformed violence in Port-au-Prince’.

- 88

- 89UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

- 90UN, ‘Haïti: la moitié de la population confrontée à une faim aiguë’, UN News, 20 September 2024.

- 91UN Security Council, ‘Viv Ansanm’, Sanctions listing.

- 92

- 93

- 94ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 95Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Haiti’, Country Profile, 15 July 2025; and ‘Open Letter to the Haitian Transitional Government Demanding Action on Gender-Based Violence’, 20 February 2025.

- 96R. Opota and H. Cadet, ‘Silent Crisis: The Long Healing Process of Survivors of Sexual Violence in Haiti’, Online article, UNICEF, 26 June 2025; Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, ‘Haiti: Sexual and gender-based violence, including acts perpetrated by criminal groups’, Query Response HTI201783.E, 5 February 2024; Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), ‘Haiti’, Public Health Situation Analysis, 4 October 2024.

- 97Human Rights Watch, ‘Haiti: Scarce Protection as Sexual Violence Escalates’, 25 November 2024.

- 98Global Protection Cluster, ‘Protection des personnes déplacées internes en Haïti’, Advocacy Brief, May 2024.

- 99Global Protection Cluster, ‘Haiti’, Protection Analysis Update, September 2025.

- 100UNICEF, ‘Haiti’s children under siege: The staggering rise of child abuse and recruitment by armed groups’, Press Release, 7 February 2025.

- 101UN, ‘Secretary-General’s remarks to the Security Council – on Haiti’, Statement, 28 August 2025.

- 102Agence France-Presse, ‘Sexual Violence Against Children Soars in Haiti: UN’, Barron’s, 7 February 2025.

- 103Ibid.

- 104Amnesty International, ‘Gang’s assault on childhood in Haiti’, Report, 12 February 2025.

- 105Human Rights Watch, ‘Haiti: Scarce Protection as Sexual Violence Escalates’, Report, 25 November 2024.

- 106

- 107

- 108‘Children and armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 7.

- 109‘Haiti: Child recruitment by armed groups surges 70 per cent’, UN News, 24 November 2024.

- 110Amnesty International, ‘Gangs’ assault on childhood in Haiti’.

- 111UNICEF, ‘Haiti’s children under siege: The staggering rise of child abuse and recruitment by armed groups’.