Conflict Overview

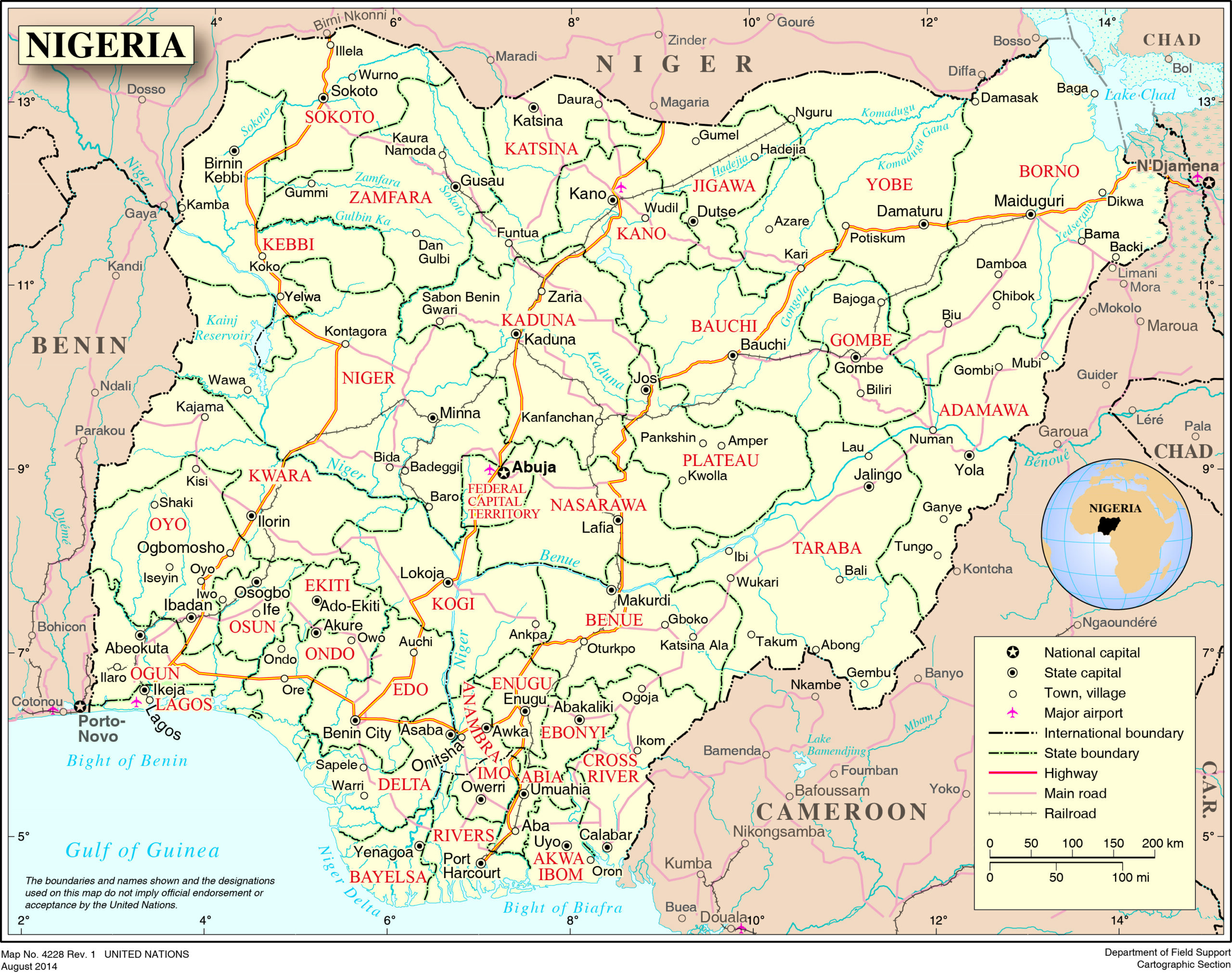

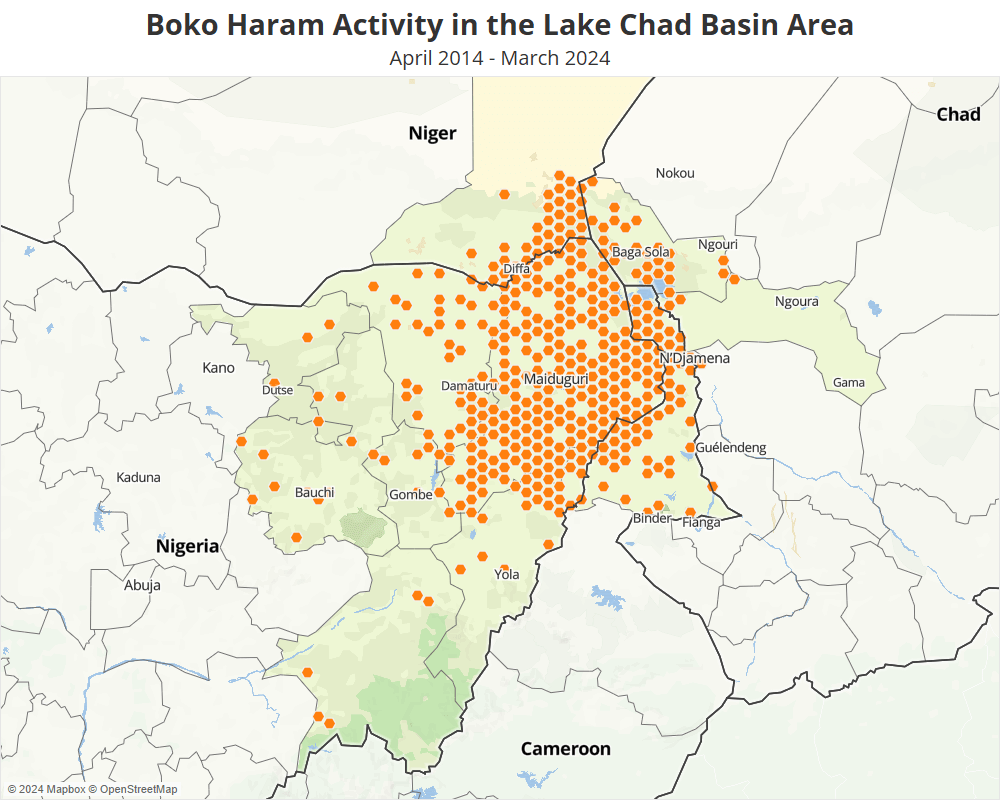

Over the past decade, Nigeria has been involved in armed conflicts with non-State armed groups on its territory – notably Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), which in turn have fought each other. Since 2015, the African Union (AU) Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) – comprising soldiers from Cameroon, Chad, Niger (until its withdrawal in 2025) and Nigeria, as well as non-combat troops from Benin – has been supporting Nigerian State forces in combating Boko Haram and ISWAP. Local militia – the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) – have also been supporting the authorities against Boko Haram.

Key Events Since 1 July 2024

Nigeria remains affected by widespread and escalating insecurity, with two non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) continuing between the State and organized armed groups during the reporting period: one with Boko Haram and the other with ISWAP. These two non-State armed groups also continued to fight each other in a separate NIAC. The north-eastern states of Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe remain the epicentre of the fighting, with both armed groups regularly targeting civilians in attacks and murdering or abducting many others.

The Nigerian Armed Forces have conducted indiscriminate airstrikes, some causing a significant number of civilian casualties. The military’s ability to respond effectively to the insecurity generated by armed groups has been hampered by weakening regional cooperation, most notably by Niger’s withdrawal from the MNJTF in March 2025. This created a security vacuum along the shared border with the other Lake Chad Basin nations, including Nigeria – one swiftly exploited by armed groups and criminal networks, further destabilizing the region.1G. Tejeda, ‘The Islamic State West Africa Province’s Tactical Evolution Fuels Worsening Conflict in Nigeria’s Northeast’, The Soufan Center, 21 May 2025.

On Christmas Day 2025, the United States entered the conflict in Nigeria, ostensibly against ISWAP, launching airstrikes on the basis that Islamic State was committing a ‘genocide’ against Christians in the country. The president said in a post on his Truth Social platform: ‘Tonight, at my direction as Commander in Chief, the United States launched a powerful and deadly strike against ISIS Terrorist Scum in Northwest Nigeria, who have been targeting and viciously killing, primarily, innocent Christians, at levels not seen for many years, and even Centuries!’2E. Egbejule, ‘US carries out strikes on Nigeria targeting Islamic State militants, Trump says’, The Guardian, 26 December 2025. While the Nigerian government rejected the premise of a genocide, it declared that not only had it consented to the airstrikes but it had also provided intelligence to the United States on possible targets.3‘Nigeria provided US with intelligence for strikes on Islamist militants, says foreign minister – as it happened’, The Guardian, 26 December 2025.

But the precise identity of the targeted group was disputed. Jabo, a village in the north-western state of Sokoto, is not an ISWAP stronghold but rather under the control of the Lakurawa group whose ties with Islamic State are said to be ‘unproven’.Experts at the Institute for Security Studies claimed in a December 2025 report that ‘Lakurawa now cooperates with Boko Haram and operates as a hybrid actor, blurring the line between religious extremism and organised crime.’4 T. Adebayo, C. Delanga, and R. Hoinathy, ‘Lakurawa: a hybrid jihadi-criminal group on Nigeria’s fragile borderlands’, Report, Institute for Security Studies, 10 December 2025, p 2. ISWAP has its strongholds in the north-east of the country.5O. Adetayo and T. Omolehin, ‘US launches airstrike on ISIS militants in Nigeria’, PBS, 26 December 2025. It was subsequently claimed, however, that the targets were foreign Islamic State fighters entering Nigeria from the Sahel.6‘US air strikes in Nigeria targeted IS group fighters trying to enter from Sahel, govt says’, France 24, 27 December 2025.

The US airstrike involved ‘about a dozen Tomahawk missiles launched from a US Navy warship in the Gulf of Guinea’. Nigeria’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Yusuf Tuggar, claimed that no specific religion had been targeted. After the strike, US Secretary of State for Defense Pete Hegseth posted on social media platform X that there was ‘more to come’. A US defence official, however, speaking under condition of anonymity, told the media that another strike did not appear to be imminent.7Reuters, ‘Why Nigeria Okayed US Strikes On ISIS After Disputing Claim Of Christian Genocide’, NDTV World, 27 December 2025.

The Humanitarian Situation

Competition over scarce natural resources has fuelled additional layers of violence outside the armed conflicts. The Niger Delta continues to be a focal point of violence, where militias contend for dominance over oil reserves. Although not regulated by international humanitarian law (IHL), rising tensions between different pastoralist communities across central and southern regions regularly harm local populations. Economic hardship and widespread discontent have exacerbated the crisis. A surge in inflation since late 2023 sparked nationwide protests over the government’s mismanagement of the economy and the nation’s food resources. The protests have been met with State repression through mass detentions and use of live ammunition.8Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Police Used Excessive Force to Violently Quash #Endbadgovernance Protests’, Press release, 28 November 2024.

The humanitarian crisis has been further aggravated by recurrent flooding. Catastrophic floods in September 2024 and May 2025 destroyed entire villages, killed thousands, and provoked widespread food insecurity, prompting many to move to other, safer areas.9UN, ‘Deadly Flooding in Nigeria Displaces Thousands’, UN News, 2 June 2025. In 2024, Nigeria experienced one of the highest levels of displacement in West Africa, with an estimated 3.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) across the country by year’s end. More than half were in Borno state.10I. Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’, HumAngle, 22 May 2025.

The level of severe malnutrition was particularly acute in the north.11M. Kessous, ‘Dans le nord du Nigeria, « le fléau vertigineux » de la malnutrition’, Le Monde, 23 October 2025. Thus, by early 2025, more than 2.5 million children were at risk of acute malnutrition in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states,12UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘2025 Humanitarian Needs & Requirements Overview Sahel’, 3 June 2025, p 38; K. Bitrus, ‘Displaced Nigerians “Will Stay” in Closing Camps amid Fears of Boko Haram’, Al Jazeera, 19 September 2025. while over the course of the first half of the year, more than 600 died from malnutrition in Katsina state in the north-west – a rise of 208 per cent compared to the same period in 2024.13‘Malnutrition in Nigeria Killed 652 Children in Past Six Months, MSF Says’, Al Jazeera, 26 July 2025. As the President of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Belgium declared: ‘Children are dying, the crisis is out of control, and the outlook is worsening given the cuts to international aid budgets.’14‘Malnutrition in Nigeria: “I Don’t Know How to Say It Any More Clearly. This Is an Emergency”’, Doctors Without Borders USA, 11 September 2025.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

Three existing NIACs continued during the reporting period:

- Nigeria (supported by the MNJTF) v Boko Haram.

- Nigeria (supported by the MNJTF and, since 26 December 2025, the United States) v ISWAP.

- Boko Haram v ISWAP.

Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and other rules of customary IHL apply to all three NIACs. Nigeria is also a State Party to Additional Protocol II of 1977,15Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978. which applies to the NIACs between Nigeria and, respectively, Boko Haram and ISWAP. These conflicts meet the additional requirements of Article 1(1) of the Protocol – specifically the need for a level of territorial control that enables them to mount sustained military operations and implement the Protocol. The NIAC between Boko Haram and ISWAP is not regulated by the Protocol as it requires one of the parties to be the territorial State.16The Protocol applies to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups’. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II.

Nigeria is a State Party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, having ratified it in 2001.17Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002. Nigeria is a situation that has been under preliminary examination by the Court for more than fifteen years, with the opening of the examination of the made public by the Court on 18 November 2010. This examination has focused on alleged crimes committed by Boko Haram since July 2009 and by the Nigerian Security Forces since the beginning of the NIAC with Boko Haram since June 2011, but has also examined alleged crimes ‘falling outside the context of this conflict’.18ICC, ‘Preliminary examination: Nigeria’, accessed 1 December 2025.

On 11 December 2020, the then Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Fatou Bensouda, announced that her preliminary examination had found a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes and crimes against humanity had been committed. In March 2024, on a visit to Nigeria, Deputy Prosecutor Mame Mandiaye Niang stressed that the Office was giving ‘a chance to the principle of complementarity in Nigeria’, but that it remained committed ‘to move forward with investigations in the absence of genuine efforts by Nigerian authorities to bridge existing impunity gaps’.19Ibid.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

The period under review saw continued attacks against civilian infrastructure across Nigeria. The conduct of hostilities in populated areas regularly involved significant destruction of churches and supplies of humanitarian aid as well as pillage of private property. Civilians were regularly attacked, with particular concerns about Nigerian Air Force airstrikes in populated areas and attacks by the two non-State armed groups, including through increased recourse to suicide bombings. Frequent use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) caused civilian casualties on the roads, while there were multiple cases of unlawful, forced displacement.

Allegations persisted of arbitrary detention, inhuman treatment, and enforced disappearance by governmental forces and non-State armed groups alike. Armed groups frequently kidnapped women and children for ransom – hostage-taking is a specific war crime. Boko Haram and ISWAP continued to recruit children for sexual purposes or for use in combat; recruitment of children under fifteen years of age are likewise war crimes.

Civilian Objects under Attack

Under customary IHL, attacks may only be directed against military objectives. Attacks must not be directed against civilian objects.20International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives21ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. and, as such, are protected against attack.22ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 10: ‘Civilian Objects’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.23ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

Attacks directed against civilian objects

Both Boko Haram and ISWAP fighters frequently attacked and destroyed civilian objects, burning or firing upon shops and homes.24B. Rukanga and O. Nkechi, ‘Nigeria Military Kills 16 Civilians in Zamfara Air Strike “Mistake”’ BBC, 13 January 2025; ‘Boko Haram’s Latest Attacks Displace Thousands of Christians in Nigeria – International Christian Concern’, Persecution.org, 24 January 2025. On 13 January 2025, for instance, fighters said to belong to Boko Haram attacked two communities in Borno state, shooting indiscriminately and setting fire to homes.25‘Boko Haram Terrorists Strike Chibok Again; Kill Many, Burn Houses And Church’, Sahara Reporters, 14 January 2025. A resident described a gun battle between the fighters and Nigerian soldiers that lasted from eleven o’clock at night until four o’clock in the morning, saying: ‘I don’t know the number of casualties now, but many houses and properties were destroyed.’26Ibid. ISWAP claimed responsibility for an attack against Banga village in April 2025 in which its fighters burned down at least thirty homes.27I. Anyaogu, ‘ISWAP Claims Responsibility for Deadly Attacks in Nigeria’, Reuters, 21 April 2025.

Attacks against cultural property

Under customary IHL, cultural and religious property, including places of worship, holy sites, and objects of spiritual importance, is afforded special protection against attack.28ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 38: ‘Attacks Against Cultural Property’. See also Art 18, Additional Protocol II. The reporting period saw repeated attacks against churches by Boko Haram fighters as part of their larger offensives on, predominantly, Christian communities in Borno state. In January 2025, Boko Haram fighters destroyed the Ekklesiyar Yan’uwa church as part of an attack on a village, threatening residents and demanding they convert to Islam.29O. Abiola, ‘Boko Haram Terrorists Burn Church in Borno, Kill Villagers’, Naija News, 12 January 2025. A local farmer described how the population were living in fear: ‘They burned down our church and homes. Many of us have lost everything.’30‘Boko Haram Kills Pastor, Two Other Christians in NE Nigeria’, Morningstar News, 10 February 2025.

Attacks against humanitarian aid

IHL requires that parties to armed conflicts respect impartial humanitarian assistance.31ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’. See also Art 16, Additional Protocol II. There were, however, frequent attacks by armed groups on convoys transporting goods, in particular those with humanitarian aid desperately needed by the civilian population. Aid workers using the Gajiram to Monguno route – a vital humanitarian and civilian access corridor in Borno – have documented repeated incidents of abductions by individuals from armed groups.32See eg: ‘Road Access Constraints on the Gajiram-Monguno Corridor: Evolving IVCP Trends and Operational Risks’, SARI Global, 8 October 2025.

The offices of humanitarian aid organizations have also been attacked. On 26 February 2025, for instance, members of an unidentified armed group entered Solidarités International’s office in Monguno and set it ablaze, kidnapping two security guards and destroying six vehicles belonging to a local car rental company. The seriousness of the attack led humanitarian agencies to suspend their activities for two days.33OCHA, ‘Nigeria: Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe (BAY) States’, Situation Report, 24 April 2025, p 5.

Attacks against medical facilities

Under IHL, medical units and transports must be protected and not attacked.34ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28: ‘Medical Units’. Arts 7, 9, 10, and 11, Additional Protocol II. Serious violations of these obligations are war crimes.35ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. The reporting period, however, saw regular attacks on medical activities in Nigeria, particularly in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states.36Safeguarding Health in Conflict and Insecurity Insights, ‘Epidemic of Violence: Violence Against Health Care in Conflict 2024’, Report, pp 52–53. Most incidents involved ISWAP or Boko Haram fighters.

In Nigeria, non-State armed groups frequently attack the aid sector because they perceive humanitarian workers as collaborating with the government. This has led an increasing number of humanitarian and health organizations to cease operations due both to the insecurity and a funding crisis, risking the deterioration of the already severe health situation.37OCHA, ‘2025 Humanitarian Needs & Requirements Overview Sahel’, p 38. As of early 2025, seventy per cent of medical facilities had either closed or were operating at reduced capacity; half of all nutrition centres were also impacted.38Ibid.

Civilians under Attack

Under customary IHL, civilians enjoy general protection from the effects of hostilities, unless and for such time as they directly participate in hostilities.39ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Accordingly, parties to armed conflicts must at all times distinguish between combatants and civilians, and are prohibited from directing attacks against civilians.40ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants’ In case of doubt, persons should be treated as civilians.41ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. The accompanying commentary states that in NIACs, ‘the issue of doubt has hardly been addressed in State practice, even though a clear rule on this subject would be desirable as it would enhance the protection of the civilian population against attack.’ One ‘cannot automatically attack anyone who might appear dubious….’ The same approach with respect to IACs ‘seems justified’ in NIACs. Civilians may be incidentally affected by attacks against lawful targets. However, such attacks must be proportionate,42ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’. and the attacker must take all feasible precautions to avoid or, in any event to minimize, incidental civilian deaths and injuries to civilians (and damage to civilian objects).43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’.

Airstrikes in populated areas

In the course of the reporting period, both the Nigerian Air Force and the MNJTF regularly conducted airstrikes targeting non-State armed groups on Nigerian territory. These operations often involved the killing of civilians, raising significant concerns about compliance with IHL rules on the conduct of hostilities. On 31 October 2024, for instance, Chadian military forces in the MJNTF conducted an airstrike on the island of Tilma, on the Nigerian side of Lake Chad, targeting fishermen mistakenly identified as Boko Haram fighters. A military officer sought to justify the error by claiming that Boko Haram ‘often blend in with fishermen and farmers whenever they commit their crimes’, emphasizing the difficulties they had in distinguishing combatants from civilians.44‘Nigeria. L’armée tchadienne accusée d’avoir tué par erreur des « dizaines » de pêcheurs’, Ouest-France, 31 October 2024. However, eyewitness accounts indicate that a fighter jet had ‘circled’ the island before dropping multiple bombs on an area where civilians were clearly trying to escape.45Ibid.

Further strikes followed that also killed significant numbers of civilians. On 25 December 2024, at least ten were killed in an airstrike by the Nigerian Air Force that was said to be targeting non-State armed group fighters.46T. Obiezu, ‘Nigeria Probes Christmas Day Airstrike That Killed 10’, Voice of America, 26 December 2024. In January 2025, another strike in Zamfara state killed at least sixteen and injured several others, again due to a mistake of target identification.47Human Rights Watch, ‘Nigeria : Une frappe aérienne militaire a tué des civils’, Press release, 15 January 2025. The following month, six civilians were reported killed by a Nigerian airstrike near Zakka village with the munitions launched after members of the non-State armed group had already left the area.48‘Au Nigeria, six civils tués par un avion militaire, dix selon Amnesty International’, TV5 Monde Info, 16 February 2025.

The recurring nature of these ‘mistakes’ strongly suggests that at the least, the Nigerian Armed Forces and the MNJTF have failed to take all feasible measures to verify that targets are lawful military objectives, as required by IHL. The accumulation of errors demonstrates a pattern of non-compliance.

Attacks directed against civilians

Nigeria has experienced a sharp escalation in attacks by non‑State armed groups, many of which targeted the civilian population. Throughout the reporting period, both Boko Haram and ISWAP targeted farmers, villagers, and religious minorities, killing and injuring many hundreds of civilians. In early September 2024, around 150 fighters, said to be from Boko Haram, attacked the village of Mafa, killing more than eighty residents they had accused of supporting the Nigerian Armed Forces.49‘Au moins 81 morts dans une attaque présumée de Boko Haram au Nigeria’ TV5 Monde Info, 3 September 2024. On 26 April 2025, while working on their land in Gwoza region, at least fourteen farmers were killed and an unknown number of others injured in a Boko Haram attack.50‘Au Nigeria, au moins 14 agriculteurs tués et 4 blessés lors d’une attaque djihadiste’, TV5 Monde Info, 27 April 2025.

The reporting period also witnessed a resurgence of suicide bombings, most attributable to Boko Haram. In late June 2024, Boko Haram conducted suicide bombings across three locations in Borno state over the course of two days.51A. Ewang, ‘Resurgence of Suicide Bombings in Nigeria’s Boko Haram Conflict’, Human Rights Watch, 24 June 2025. The first attack was in Gwoza, where a woman carrying a baby detonated an explosive device during a wedding reception. The subsequent attacks occurred near a hospital and then at the funeral of the victims of the first attack. Together, the bombings killed more than thirty civilians and injured another forty-two, including many children and women. A few weeks later, another explosion occurred in a tearoom in the same region, killing nineteen and injuring more than twenty others.52T. Leclerc, ‘Nigéria: L’explosion d’une Bombe Fait 19 Morts et Une Vingtaine de Blessés’, Ouest-France, 8 January 2025; ‘Au Nigeria, l’explosion d’une bombe fait 19 morts et une vingtaine de blessés dans un salon de thé’, Le Monde, 1 August 2024.

Use of improvised explosive devices

Throughout the reporting period, improvised landmines and remotely controlled or command-detonated IEDs continued to pose a grave and persistent threat to civilians across Nigeria. When deployed in populated areas or locations frequently accessed by civilians, these explosive devices tend to have indiscriminate effects.53ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’; and Rule 12: ‘Definition of Indiscriminate Attacks’. If they are not directed at specific military objectives, this renders their use a violation of the principle of distinction. Where feasible precautions are not taken to avoid, and in any event to minimize, civilian harm, this will also violate the IHL rule of precautions in attack.

Improvised anti-vehicle mines are regularly placed on strategic routes that also serve as a lifeline for economic activities in the south of Borno state, resulting in the death and injury of many civilians. For instance, in April 2025, a mine killed at least eight individuals travelling in a bus in Borno state.54K. Adeniyi, ‘Huit Morts et Onze Blessés Dans l’explosion d’une Mine Dans Le Nord-Est Du Nigéria’, Anadolu Ajansı, 14 April 2025. A month earlier, a mine killed four passengers in a commercial bus in the same region.55Ibid; cf also ‘Roadside Bomb Blast Kills 26 in Nigeria’s Restive Northeast’, Al Jazeera, 29 April 2025.

On 21 June 2025, a woman detonated an IED among a crowd at a fish market in Konduga town, killing at least twelve.56Ewang, ‘Resurgence of Suicide Bombings in Nigeria’s Boko Haram Conflict’. Sources suggest the explosion occurred when the market was busiest and at a location known for gathering civilians in support of the Nigerian Armed Forces.57Leclerc, ‘Nigéria: L’explosion d’une Bombe Fait 19 Morts et Une Vingtaine de Blessés’. But given the lack of evidence that at the time of the attack these civilians were directly participating in hostilities, they remained civilians protected from attack under IHL.

Forced displacement

Nigeria is one of the countries most affected by conflict-related displacements on the African continent, with an estimated 3.7 million IDPs.58Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’. Under customary IHL applicable in all armed conflicts, parties are prohibited from ordering the displacement of the civilian population in relation to the conflict unless required for the security of the civilians or for imperative military reasons.59ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 129: ‘The Act of Displacement’. See also Art 17, Additional Protocol II. Breaches of these prohibitions are typically serious violations of IHL.60ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. Furthermore, such displacement must be temporary, with all possible measures taken to ensure proper shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition and that members of the same family are not separated.61ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 131: ‘Treatment of Displaced Persons’. The prohibition aims to protect civilian populations from arbitrary or punitive displacement and to uphold their rights to remain in or return to their homes.62ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’.

The continued displacement of civilians is particularly pronounced in areas affected by the armed conflicts where significant civilian harm has occurred. Many have decided to leave due to the overall insecurity and the specific fear of violence at the hands of State or non-State forces.63Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’. Monitoring indicated that the displacement entailed the relocation of entire villages due to persistent pressures, especially the enforcement of ‘taxes’ and the targeting of civilians by ISWAP and Boko Haram.64A. Salkida, ‘ISWAP Overruns Key Borno Sites in Coordinated Assault’, HumAngle, 14 May 2025.

The prospect of return remains minimal while the insecurity persists. As an IDP told a journalist: ‘If our hometown were peaceful, we would return immediately. Farming is all we know. But they won’t let us live – they seize our crops, invade our homes, and kill at will.’65Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’. Residents have described an environment of fear and coercion, with one noting: ‘If the community continued to refuse their errands, they would return to slaughter everyone, and burn the village down.’66Ibid. Many have also felt compelled to flee because they are unable to produce the food to sustain themselves and their families. As a farmer describes the situation created by recurring alleged Boko Haram attacks on his community: ‘Even if you are starving and food is scarce, you can’t go to the farm. When we try, they chase us away or even kill us.’67N. Ijeoma, ‘Nigeria’s Farmers on the Frontline against Boko Haram: “We Fear for Our Souls”’, BBC, 22 October 2025.

Reports indicate that IDPs faced similar threats and extremely poor living conditions when in government-run camps. They are overcrowded, with heightened risks of disease and sexual or gender-based violence, and insufficient access to food and healthcare.68OCHA, ‘2025 Humanitarian Needs & Requirements Overview Sahel’, p 38. Many children are unable to pursue their education, as there is no arrangement for children to be taught in the camps.69Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Violence and Widespread Displacement Leave Benue Facing a Humanitarian Disaster’, Report,10 July 2025. Those who try to return to their homes face obstruction and intimidation. The situation is sometimes described as a never-ending cycle of displacement.70Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’; Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Mounting Death Toll and Looming Humanitarian Crisis amid Unchecked Attacks by Armed Groups’, Report, 28 May 2025.

In light of these realities, it is reasonable to conclude that the displacement of civilians in Nigeria often occurred under duress, threats, and a generalized fear of violence. The cumulative effect of these actions, including armed groups’ threat to life and their destruction of property constitutes unlawful forced displacement under IHL. The Nigerian authorities in turn have not complied with their obligation to ensure that IDPs have basic shelter, hygiene, health, safety, and nutrition.71ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 131: ‘Treatment of Displaced Persons’.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

Under customary IHL, special protection is afforded to ‘protected persons’, including several categories of civilians who face a specific risk of harm, such as women, children, refugees, and IDPs.72ICRC, Customary IHL Rules 134–138: ‘Chapter 39. Other Persons Afforded Specific Protection’. IHL provides certain fundamental guarantees for anyone who is in the power of a party to a conflict, prohibiting torture, other inhumane or degrading treatment, all forms of sexual violence, enforced disappearance, and unfair trials.

Murder of civilians

On 12 January 2025, armed group fighters killed more than forty civilians during an attack against an agricultural community in Borno state.73H. Isilow, ‘Nigeria: Plusieurs Agriculteurs Tués Lors d’une Attaque de Terroristes Présumés’, Anadolu Ajansı, 14 January 2025. The attackers reportedly gathered the farmers and fishermen, separated the men, and shot them at close range.74Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria. Boko Haram doit mettre un terme à sa frénésie meurtrière’, 15 January 2025. Those who tried to escape were chased and killed, while dozens of others were injured. During the reporting period, evidence has also emerged about the mass execution of individuals captured by armed groups. Video footage reportedly shows how ISWAP executes groups of individuals who confess loyalty to the government.75Brant [@BrantPhilip_], ‘ISWAP Released Its’ New Video Titled “The Consequence of Treason”, or “Sakamakon Cin Amana” in Hausa. My Observations’, 17 July 2025.

Pillage

IHL prohibits pillage and the unlawful destruction of property during all armed conflicts. Pillage is the forcible appropriation by members of armed forces of private property and constitutes a war crime.76ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 52: ‘Pillage’. Destruction of property not justified by military necessity is likewise unlawful.77ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 50: ‘Destruction and Seizure of Property of an Adversary’.

Evidence indicates that Boko Haram and ISWAP have regularly violated these obligations. Reports show a pattern of fighters burning down homes and looting civilian shops, personal belongings, and livestock.78‘Au moins 81 morts dans une attaque présumée de Boko Haram au Nigeria’. Testimonies recount how fighters ‘killed many people and burned many shops and houses’.79‘Tinubu: Attack on Yobe Cowardly’, This Day, 5 September 2024. In none of the recorded incidents did available evidence suggest the measures were in any way justified by imperative military necessity. Moreover, the systematic nature of the violations forced large groups of civilians to flee their homes in search of safety.80Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Violence and Widespread Displacement Leave Benue Facing a Humanitarian Disaster’; Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’.

That non-State armed groups commit these acts does not, however, discharge the Nigerian government from its duty to ensure the protection of civilian property.81ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 144: ‘Ensuring Respect for International Humanitarian Law Erga Omnes’; and Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’. There are credible allegations that the government was aware of some of the violations perpetrated by these armed groups, yet failed to exercise due diligence to prevent or suppress them.82Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Violence and Widespread Displacement Leave Benue Facing a Humanitarian Disaster’.

Arbitrary deprivation of liberty, torture, and death in detention

Under IHL, any deprivation of liberty must be lawful, non-arbitrary, and carried out with appropriate legal safeguards.83ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 99: ‘Deprivation of Liberty’. Persons deprived of liberty must be treated humanely at all times, with absolute prohibitions on torture and other ill-treatment.84Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 90: ‘Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment’. Authorities must ensure detainees have access to medical care, are held in humane conditions, and are protected from violence or reprisals. The death of a detainee in custody, particularly under suspicious conditions, may involve a war crime and needs to be effectively investigated.85Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’. Enforced disappearance – secret detention and the failure to disclose the fate or whereabouts of a detainee – violates IHL’s prohibition of the practice as well as the requirement to register detainees and the right of families to know the fate of their relatives.86ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 98: ‘Enforced Disappearance’; Rule 117: ‘Accounting for Missing Persons’; Rule 123: ‘Recording and Notification of Personal Details of Persons Deprived of their Liberty’; and Rule 125: ‘Correspondence of Persons Deprived of Their Liberty’.

Allegations of torture, extortion, and forced confessions by Nigerian security forces persisted during the reporting period, along with breaches of the right of anyone charged with a crime to a fair trial. Many detainees were arrested on the basis of alleged affiliation with a non-State armed group, but often without hard evidence to support this. They then wait years for access to courts, in breach of the peremptory rule of habeas corpus. Also arrested and detained, often for extended periods, are women and children supposedly linked in some way to either Boko Haram or ISWAP.87I. Adeyemi, ‘Miscarriage, Childbirth in Jail: The Failure of Nigeria’s Criminal Justice System’, HumAngle, 17 July 2025.

Journalists, activists, and government critics have increasingly faced abductions, unlawful arrests, and detentions, further shrinking civic space.88E. Okakwu, ‘Chained and Blindfolded: Nigerian Journalist Segun Olatunji Recounts His Detention’, Committee to Protect Journalists, 31 July 2024. In one notable case, Isaac Bristol, a social commentator, was reported missing in August 2024 and was only confirmed to be in police custody three weeks later.89O. Sunday, ‘Police Finally Confirm Arrest of “missing” Whistleblower PIDOM’, Daily Post Nigeria, 24 August 2024. He had been arrested in his hotel room for alleged serious offences concerning obtaining or release of information pertaining to military operations.90Ibid.

This pattern of repression has coincided with legislative efforts that erode fundamental freedoms. In July 2024, a federal legislator introduced the Counter Subversion Bill, purportedly to strengthen Nigeria’s counterterrorism framework. However, the proposed law was criticized for its broad and troubling provisions, such as imprisonment or fines for failing to recite the national anthem or for perceived ‘insults’ towards the country’s leadership.91T. Oyedokun, ‘10 Key Things to Know about the Counter Subversion Bill’, Business Day NG, 14 August 2024. Following widespread public condemnation, the Counter Subversion Bill was withdrawn. Nevertheless, it attests to the level of ongoing threats to freedom of expression and civic space in Nigeria.

Moreover, reports also underscore the ongoing risks of false accusation, coerced confessions, collective punishment, and prolonged detention without due process, including of women and children.92I. Adeyemi, ‘Miscarriage, Childbirth in Jail: The Failure of Nigeria’s Criminal Justice System’; see also: ‘Nigeria – Women Support Women Community Network’, UNODC. Recent estimates indicate that of the 77,800 inmates across 240 prisons in the country, only 26,898 have been convicted of a crime.93A. Jamiu, ‘What’s behind Nigeria’s Increase in Jailbreaks?’, Deutsche Welle, 4 March 2025. The reporting period has also evidenced cases of death in custody in suspicious circumstances.94Amnesty International, ‘Résumé régional Afrique’, Annual Report 2024/25.

Moreover, conditions of detention, including for those accused of affiliation with armed groups, continue to raise significant IHL concerns. There is severe overcrowding and prisons have outdated infrastructure.95World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), ‘Global Torture Index 2025: Nigeria Fact Sheet’, 2025; Jamiu, ‘What’s behind Nigeria’s Increase in Jailbreaks?’. Multiple testimonies depict how women fleeing captivity by armed groups are detained by Nigerian Armed Forces on suspicion of association with armed groups and are often subjected to severe mistreatment.96C. Asadu, ‘A Report Says Women Were Abused in Nigerian Military Cells after Fleeing Boko Haram Captivity’, Associated Press, 10 June 2024. The lack of access to adequate food, water, sanitation, and medical care violates the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment under IHL.

In addition to abuses perpetrated by the authorities, abductions and kidnappings by armed groups remain widespread in conflict-affected areas. Hundreds of abductions are reported monthly,97U. A. Zanna, ‘Boko Haram/ISWAP Resurgence in Lake Chad Region Sparks Alarm’, HumAngle, 10 April 2025. including of children.98‘Nigeria: 20 étudiants en médecine kidnappés dans l’est du pays, les ravisseurs réclament une rançon’, Ouest-France, 17 August 2024. Armed groups often perform mass abductions, such as in August 2024, when twenty medical students were kidnapped in East Nigeria.99Ibid. An inquiry report by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women describes how girls are often kidnapped for ransom, forced into marriage, or used for trafficking or prisoner exchange.100UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, ‘Nigeria: UN Committee Finds Grave and Systematic Violations Persist after Chibok Mass Abduction of Schoolgirls’, Press Release, 2025. Deprived of adequate nutrition, they are physically punished for any act of disobedience, including sometimes by being repeatedly raped. Many were compelled to marry fighters and to renounce their religion, with some giving birth while in captivity.101Ibid.

Medical staff are also regularly subject to kidnappings for ransom.102A. Olaoluwa and M. Abubakar, ‘Nigerian Doctors Strike Over Kidnapped Colleague’, BBC, 26 August 2024. Numerous accounts depict the evolution of kidnappings into a profitable enterprise used by armed groups. Relatives unable to pay the ransom risk their family members being murdered. Testimonies describe how they threatened ‘to burn them alive or shoot them if they didn’t pay the ransom on time.’103A. M. Abba, ‘Daily Kidnappings Plague Resettled Communities in Lake Chad Region’, HumAngle, 9 March 2025. Some individuals even witnessed their relatives being murdered due to their inability to pay.104S. Ojuroungbe, ‘Kidnappers Threaten Health Services as 109 Workers Abducted in Five Years’, Punch Newspapers, 31 August 2024; Ijeoma, ‘Nigeria’s Farmers on the Frontline against Boko Haram: “We Fear for Our Souls”’. The situation of relatives is further complicated because Nigeria introduced a law in 2022 criminalizing ransom payments, with a maximum prison sentence of fifteen years for a breach.105Olaoluwa and Mansur, ‘Nigerian Doctors Strike Over Kidnapped Colleague’. Still, many choose to pay to free their relatives, and no evidence of a conviction following such payments has been found.106Ibid; ‘Nigeria: 58 Captives Killed despite Ransoms Paid for Release’, News on Air, 28 July 2025.

Overall, where people are kidnapped with a view to compelling the Nigerian Armed Forces to do or to abstain from doing any act (or demand a ransom from the families), this is the war crime of hostage-taking.107ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 96: ‘Hostage-Taking’. In many cases, the fate and whereabouts of detainees were concealed, amounting to the war crime of enforced disappearance. Where an abduction leads to death, this may amount to murder.108Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 90: ‘Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment’; and Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’.

Protection of children

Under IHL, children are afforded special protection in armed conflicts, recognizing their particular vulnerability. Core rules prohibit recruitment or use of children under the age of fifteen years in hostilities, whether in State or non-State armed forces, and forbid their participation in combat.109ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 136: ‘Recruitment of Child Soldiers’. Children are entitled to general protection as civilians, including against direct attack, arbitrary detention, sexual violence, and ill-treatment, as well as specific guarantees such as access to food, medical care, and education. If detained, they must be held separately from adults (unless with their family) and treated in a manner appropriate to their age. Evacuation and reunification of separated children with their families are also prioritized.110ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 135: ‘Children’.

During the reporting period, incidents of recruitment and use of children, their killing or maiming,111UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, Report, UN Doc A/HRC/58/18, 8 January 2025, para 309. rape and other forms of sexual violence, and abduction were all documented. According to the United Nations, Nigeria is among the five nations in which children are most affected by violence worldwide, with more than 2,500 violations verified in 2024.112‘Hausse “sidérante” des violences contre les enfants dans les zones de guerre en 2024, s’alarme l’ONU’, RTS, 20 June 2025. Almost one thousand children were abducted for recruitment and used in combat, mainly by Boko Haram, but also by ISWAP. The training of child recruits is even depicted in an ISWAP propaganda video.113S. Malik and S. Ed, ‘Resurgent Jihadist Violence in Northeast Nigeria Part of a Worrying Regional Trend’, The New Humanitarian, 2 June 2025; M. Samuel, ‘From the Levant to Lake Chad: ISIS Fighters Fuel ISWAP Resurgence’, Good Governance Africa, 30 May 2025.

While few in number, three cases of child recruitment by the Nigerian Armed Forces were nonetheless verified.114Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, Report, para 307. Nigerian security forces often detain minors based on alleged associations with non-State armed groups, either directly or through their parents. Fortunately, all 732 verified cases resulted in their subsequent safe release.115Ibid, para 308.

Conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence

Rape and other forms of sexual violence in connection with armed conflict are prohibited and are serious violations of IHL.116ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. The conflicts in Nigeria have been marked by widespread incidents of gender-based violence. A particularly concerning trend is the rise in sexual violence perpetrated against children.117Report of the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, para 310. Most verified cases follow forced marriages and are attributed to either Boko Haram or ISWAP.118Ibid. Reports thus describe how the groups force their captives into marriage, rape them, and then turn them into sexual slaves. Sometimes they use these victims to reward fighters or motivate new recruits, leading some families to accept forced marriage as a strategy to prevent abduction.119Report of the UN Secretary-General, ‘Violences Sexuelles Liées Aux Conflits’, UN Doc S/2025/389, 15 July 2025.

Those who manage to escape captivity face severe difficulties in reintegrating into society due to the lack of adequate services.120Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Girl Survivors of Boko Haram Still Being Failed by Government Inaction – New Testimony’, Report, 9 June 2025. Indeed, some describe how they were taken to prisons, questioned, and even held for prolonged periods by the authorities owing to their ‘association’ with armed groups.121Asadu, ‘A Report Says Women Were Abused in Nigerian Military Cells after Fleeing Boko Haram Captivity’. Following release, they are left with no assistance for shelter and food.122Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Girl Survivors of Boko Haram Still Being Failed by Government Inaction – New Testimony’. As the Chair of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women describes:

The testimonies of survivors highlight not only the suffering endured during captivity, but also the profound challenges faced upon their return. These girls were failed twice, first when they were abducted, and again when so many of them were left abandoned without care or support after escaping, including those left in IDP camps.123UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, ‘Nigeria: UN Committee Finds Grave and Systematic Violations Persist after Chibok Mass Abduction of Schoolgirls’.

- 1G. Tejeda, ‘The Islamic State West Africa Province’s Tactical Evolution Fuels Worsening Conflict in Nigeria’s Northeast’, The Soufan Center, 21 May 2025.

- 2E. Egbejule, ‘US carries out strikes on Nigeria targeting Islamic State militants, Trump says’, The Guardian, 26 December 2025.

- 3‘Nigeria provided US with intelligence for strikes on Islamist militants, says foreign minister – as it happened’, The Guardian, 26 December 2025.

- 4T. Adebayo, C. Delanga, and R. Hoinathy, ‘Lakurawa: a hybrid jihadi-criminal group on Nigeria’s fragile borderlands’, Report, Institute for Security Studies, 10 December 2025, p 2.

- 5O. Adetayo and T. Omolehin, ‘US launches airstrike on ISIS militants in Nigeria’, PBS, 26 December 2025.

- 6‘US air strikes in Nigeria targeted IS group fighters trying to enter from Sahel, govt says’, France 24, 27 December 2025.

- 7Reuters, ‘Why Nigeria Okayed US Strikes On ISIS After Disputing Claim Of Christian Genocide’, NDTV World, 27 December 2025.

- 8Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Police Used Excessive Force to Violently Quash #Endbadgovernance Protests’, Press release, 28 November 2024.

- 9UN, ‘Deadly Flooding in Nigeria Displaces Thousands’, UN News, 2 June 2025.

- 10I. Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’, HumAngle, 22 May 2025.

- 11M. Kessous, ‘Dans le nord du Nigeria, « le fléau vertigineux » de la malnutrition’, Le Monde, 23 October 2025.

- 12UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘2025 Humanitarian Needs & Requirements Overview Sahel’, 3 June 2025, p 38; K. Bitrus, ‘Displaced Nigerians “Will Stay” in Closing Camps amid Fears of Boko Haram’, Al Jazeera, 19 September 2025.

- 13‘Malnutrition in Nigeria Killed 652 Children in Past Six Months, MSF Says’, Al Jazeera, 26 July 2025.

- 14‘Malnutrition in Nigeria: “I Don’t Know How to Say It Any More Clearly. This Is an Emergency”’, Doctors Without Borders USA, 11 September 2025.

- 15Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978.

- 16The Protocol applies to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups’. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II.

- 17Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002.

- 18ICC, ‘Preliminary examination: Nigeria’, accessed 1 December 2025.

- 19Ibid.

- 20International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 21

- 22

- 23ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

- 24B. Rukanga and O. Nkechi, ‘Nigeria Military Kills 16 Civilians in Zamfara Air Strike “Mistake”’ BBC, 13 January 2025; ‘Boko Haram’s Latest Attacks Displace Thousands of Christians in Nigeria – International Christian Concern’, Persecution.org, 24 January 2025.

- 25‘Boko Haram Terrorists Strike Chibok Again; Kill Many, Burn Houses And Church’, Sahara Reporters, 14 January 2025.

- 26Ibid.

- 27I. Anyaogu, ‘ISWAP Claims Responsibility for Deadly Attacks in Nigeria’, Reuters, 21 April 2025.

- 28ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 38: ‘Attacks Against Cultural Property’. See also Art 18, Additional Protocol II.

- 29O. Abiola, ‘Boko Haram Terrorists Burn Church in Borno, Kill Villagers’, Naija News, 12 January 2025.

- 30‘Boko Haram Kills Pastor, Two Other Christians in NE Nigeria’, Morningstar News, 10 February 2025.

- 31ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’. See also Art 16, Additional Protocol II.

- 32See eg: ‘Road Access Constraints on the Gajiram-Monguno Corridor: Evolving IVCP Trends and Operational Risks’, SARI Global, 8 October 2025.

- 33OCHA, ‘Nigeria: Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe (BAY) States’, Situation Report, 24 April 2025, p 5.

- 34

- 35

- 36Safeguarding Health in Conflict and Insecurity Insights, ‘Epidemic of Violence: Violence Against Health Care in Conflict 2024’, Report, pp 52–53.

- 37OCHA, ‘2025 Humanitarian Needs & Requirements Overview Sahel’, p 38.

- 38Ibid.

- 39

- 40

- 41ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. The accompanying commentary states that in NIACs, ‘the issue of doubt has hardly been addressed in State practice, even though a clear rule on this subject would be desirable as it would enhance the protection of the civilian population against attack.’ One ‘cannot automatically attack anyone who might appear dubious….’ The same approach with respect to IACs ‘seems justified’ in NIACs.

- 42ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’.

- 43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’.

- 44‘Nigeria. L’armée tchadienne accusée d’avoir tué par erreur des « dizaines » de pêcheurs’, Ouest-France, 31 October 2024.

- 45Ibid.

- 46T. Obiezu, ‘Nigeria Probes Christmas Day Airstrike That Killed 10’, Voice of America, 26 December 2024.

- 47Human Rights Watch, ‘Nigeria : Une frappe aérienne militaire a tué des civils’, Press release, 15 January 2025.

- 48‘Au Nigeria, six civils tués par un avion militaire, dix selon Amnesty International’, TV5 Monde Info, 16 February 2025.

- 49‘Au moins 81 morts dans une attaque présumée de Boko Haram au Nigeria’ TV5 Monde Info, 3 September 2024.

- 50‘Au Nigeria, au moins 14 agriculteurs tués et 4 blessés lors d’une attaque djihadiste’, TV5 Monde Info, 27 April 2025.

- 51A. Ewang, ‘Resurgence of Suicide Bombings in Nigeria’s Boko Haram Conflict’, Human Rights Watch, 24 June 2025.

- 52T. Leclerc, ‘Nigéria: L’explosion d’une Bombe Fait 19 Morts et Une Vingtaine de Blessés’, Ouest-France, 8 January 2025; ‘Au Nigeria, l’explosion d’une bombe fait 19 morts et une vingtaine de blessés dans un salon de thé’, Le Monde, 1 August 2024.

- 53ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’; and Rule 12: ‘Definition of Indiscriminate Attacks’.

- 54K. Adeniyi, ‘Huit Morts et Onze Blessés Dans l’explosion d’une Mine Dans Le Nord-Est Du Nigéria’, Anadolu Ajansı, 14 April 2025.

- 55Ibid; cf also ‘Roadside Bomb Blast Kills 26 in Nigeria’s Restive Northeast’, Al Jazeera, 29 April 2025.

- 56Ewang, ‘Resurgence of Suicide Bombings in Nigeria’s Boko Haram Conflict’.

- 57Leclerc, ‘Nigéria: L’explosion d’une Bombe Fait 19 Morts et Une Vingtaine de Blessés’.

- 58Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’.

- 59

- 60ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 61

- 62

- 63Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’.

- 64A. Salkida, ‘ISWAP Overruns Key Borno Sites in Coordinated Assault’, HumAngle, 14 May 2025.

- 65Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’.

- 66Ibid.

- 67N. Ijeoma, ‘Nigeria’s Farmers on the Frontline against Boko Haram: “We Fear for Our Souls”’, BBC, 22 October 2025.

- 68OCHA, ‘2025 Humanitarian Needs & Requirements Overview Sahel’, p 38.

- 69Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Violence and Widespread Displacement Leave Benue Facing a Humanitarian Disaster’, Report,10 July 2025.

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73H. Isilow, ‘Nigeria: Plusieurs Agriculteurs Tués Lors d’une Attaque de Terroristes Présumés’, Anadolu Ajansı, 14 January 2025.

- 74Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria. Boko Haram doit mettre un terme à sa frénésie meurtrière’, 15 January 2025.

- 75Brant [@BrantPhilip_], ‘ISWAP Released Its’ New Video Titled “The Consequence of Treason”, or “Sakamakon Cin Amana” in Hausa. My Observations’, 17 July 2025.

- 76

- 77

- 78‘Au moins 81 morts dans une attaque présumée de Boko Haram au Nigeria’.

- 79‘Tinubu: Attack on Yobe Cowardly’, This Day, 5 September 2024.

- 80Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Violence and Widespread Displacement Leave Benue Facing a Humanitarian Disaster’; Ismaila, ‘Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis’.

- 81ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 144: ‘Ensuring Respect for International Humanitarian Law Erga Omnes’; and Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’.

- 82Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Violence and Widespread Displacement Leave Benue Facing a Humanitarian Disaster’.

- 83

- 84Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 90: ‘Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment’.

- 85

- 86ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 98: ‘Enforced Disappearance’; Rule 117: ‘Accounting for Missing Persons’; Rule 123: ‘Recording and Notification of Personal Details of Persons Deprived of their Liberty’; and Rule 125: ‘Correspondence of Persons Deprived of Their Liberty’.

- 87I. Adeyemi, ‘Miscarriage, Childbirth in Jail: The Failure of Nigeria’s Criminal Justice System’, HumAngle, 17 July 2025.

- 88E. Okakwu, ‘Chained and Blindfolded: Nigerian Journalist Segun Olatunji Recounts His Detention’, Committee to Protect Journalists, 31 July 2024.

- 89O. Sunday, ‘Police Finally Confirm Arrest of “missing” Whistleblower PIDOM’, Daily Post Nigeria, 24 August 2024.

- 90Ibid.

- 91T. Oyedokun, ‘10 Key Things to Know about the Counter Subversion Bill’, Business Day NG, 14 August 2024.

- 92I. Adeyemi, ‘Miscarriage, Childbirth in Jail: The Failure of Nigeria’s Criminal Justice System’; see also: ‘Nigeria – Women Support Women Community Network’, UNODC.

- 93A. Jamiu, ‘What’s behind Nigeria’s Increase in Jailbreaks?’, Deutsche Welle, 4 March 2025.

- 94Amnesty International, ‘Résumé régional Afrique’, Annual Report 2024/25.

- 95World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), ‘Global Torture Index 2025: Nigeria Fact Sheet’, 2025; Jamiu, ‘What’s behind Nigeria’s Increase in Jailbreaks?’.

- 96C. Asadu, ‘A Report Says Women Were Abused in Nigerian Military Cells after Fleeing Boko Haram Captivity’, Associated Press, 10 June 2024.

- 97U. A. Zanna, ‘Boko Haram/ISWAP Resurgence in Lake Chad Region Sparks Alarm’, HumAngle, 10 April 2025.

- 98‘Nigeria: 20 étudiants en médecine kidnappés dans l’est du pays, les ravisseurs réclament une rançon’, Ouest-France, 17 August 2024.

- 99Ibid.

- 100UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, ‘Nigeria: UN Committee Finds Grave and Systematic Violations Persist after Chibok Mass Abduction of Schoolgirls’, Press Release, 2025.

- 101Ibid.

- 102A. Olaoluwa and M. Abubakar, ‘Nigerian Doctors Strike Over Kidnapped Colleague’, BBC, 26 August 2024.

- 103A. M. Abba, ‘Daily Kidnappings Plague Resettled Communities in Lake Chad Region’, HumAngle, 9 March 2025.

- 104S. Ojuroungbe, ‘Kidnappers Threaten Health Services as 109 Workers Abducted in Five Years’, Punch Newspapers, 31 August 2024; Ijeoma, ‘Nigeria’s Farmers on the Frontline against Boko Haram: “We Fear for Our Souls”’.

- 105Olaoluwa and Mansur, ‘Nigerian Doctors Strike Over Kidnapped Colleague’.

- 106Ibid; ‘Nigeria: 58 Captives Killed despite Ransoms Paid for Release’, News on Air, 28 July 2025.

- 107

- 108Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 90: ‘Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment’; and Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’.

- 109

- 110

- 111UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, Report, UN Doc A/HRC/58/18, 8 January 2025, para 309.

- 112

- 113S. Malik and S. Ed, ‘Resurgent Jihadist Violence in Northeast Nigeria Part of a Worrying Regional Trend’, The New Humanitarian, 2 June 2025; M. Samuel, ‘From the Levant to Lake Chad: ISIS Fighters Fuel ISWAP Resurgence’, Good Governance Africa, 30 May 2025.

- 114Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, Report, para 307.

- 115Ibid, para 308.

- 116ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 117Report of the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, ‘Children and Armed Conflict’, para 310.

- 118Ibid.

- 119Report of the UN Secretary-General, ‘Violences Sexuelles Liées Aux Conflits’, UN Doc S/2025/389, 15 July 2025.

- 120Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Girl Survivors of Boko Haram Still Being Failed by Government Inaction – New Testimony’, Report, 9 June 2025.

- 121Asadu, ‘A Report Says Women Were Abused in Nigerian Military Cells after Fleeing Boko Haram Captivity’.

- 122Amnesty International, ‘Nigeria: Girl Survivors of Boko Haram Still Being Failed by Government Inaction – New Testimony’.

- 123UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, ‘Nigeria: UN Committee Finds Grave and Systematic Violations Persist after Chibok Mass Abduction of Schoolgirls’.