Conflict Overview

Conflict History

The origins of the multiple NIACs in the Central African Republic (CAR) are found in the fighting that broke out in December 2012 and which saw an alliance of Muslim armed groups known as Séléka oust President François Bozizé three months later. Another alliance, this time of Christian non-State armed groups referred to as Anti-Balaka (meaning ‘invincible’ in Sango), then formed to confront the new government in Bangui.1International Commission of Inquiry on the Central African Republic, Final Report, UN Doc S/2014/928, 22 December 2014. To support the government’s efforts to stabilize the political and security situation, the United Nations (UN) Security Council established the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in CAR – MINUSCA – in 2014.2UN Security Council Resolution 2149, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 10 April 2014, operative para 18. The mission’s mandate was later broadened to include protection of civilians, humanitarian aid, disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of armed group fighters, and human rights monitoring.3See MINUSCA, ‘Mandate’. As of 1 June 2025, the Mission’s deployed military component totalled 14,054 troops. ‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 61. Under its Resolution 2759, the UN Security Council extended MINUSCA’s mandate until 15 November 2025. UN Security Council Resolution 2759, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 14 November 2024, operative para 32. Operative para 28 of Resolution 2800, adopted on 13 November 2025 by fourteen votes to nil with one abstention (the United States), extended the mission’s mandate until 15 November 2026.

In February 2019, the government and fourteen armed groups signed the ‘Political Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in the Central African Republic’, which proclaimed it was a ‘comprehensive consensual agreement’ that would ‘put a definitive end to the crisis’.4L’Accord politique pour la paix et la réconciliation en République centrafricaine, UN Doc S/2019/145, 15 February 2019. It failed to achieve this goal. In 2023, President Faustin Archange Touadéra changed the nation’s constitution to allow him potentially to stay in power indefinitely,5‘Russia Pushes CAR to Choose Africa Corps Over Wagner Mercenaries’, Africa Defense Forum, 28 October 2025. a decision that led to further violence.

On 17 December 2020, ten days before presidential and parliamentary elections were due to be held, former fighters of the previously rival Séléka and Anti-Balaka groups had joined forces to establish the Coalition des patriotes pour le changement (CPC) to oppose President Touadéra.The alliance comprised the Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain (MPC); Retour, Réclamation, et Réhabilitation (3R); the Union pour la paix en Centrafrique (UPC); and the Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique (FPRC), as well as Anti-Balaka fighters from the Mokom and Ngaïssona factions. 6MINUSCA and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘Rapport public sur les violations des droits de I’Homme et du droit international humanitaire en République centrafricaine durant la période électorale, Juillet 2020–Juin 2021’, Report, p 4. The CAR Armed Forces (FACA) and its military allies have since been engaged in a non-international armed conflicts (NIAC) with the CPC, a conflict that continues to meet the minimum threshold of violence set by international humanitarian law (IHL), albeit at a relatively low level of intensity. This conflict has seen the commission of manifold war crimes.7MINUSCA and OHCHR, ‘Rapport public sur les violations des droits de I’Homme’. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), as of May 2024, 750,000 Central African citizens were seeking refuge abroad and 451,000 persons were internally displaced. OCHA, ‘Central African Republic: Situation Report’, 11 December 2024. With the support of the Wagner Group and the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF), State armed forces retook major cities across CAR in 2021.8Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), ‘Wagner Group Operations in Africa: Civilian Targeting Trends in the Central African Republic and Mali’, 30 August 2022. In late 2023, Wagner was rebranded in Africa Corps and placed under the supervision of the Russian Ministry of Defence.9S. Ritter, ‘The New “Africa Corps”: Russia’s Wagner Rebranding’, Energy Intelligence, 24 May 2024, http://bit.ly/4hesCSg. As a result, its members may best be considered as State agents.

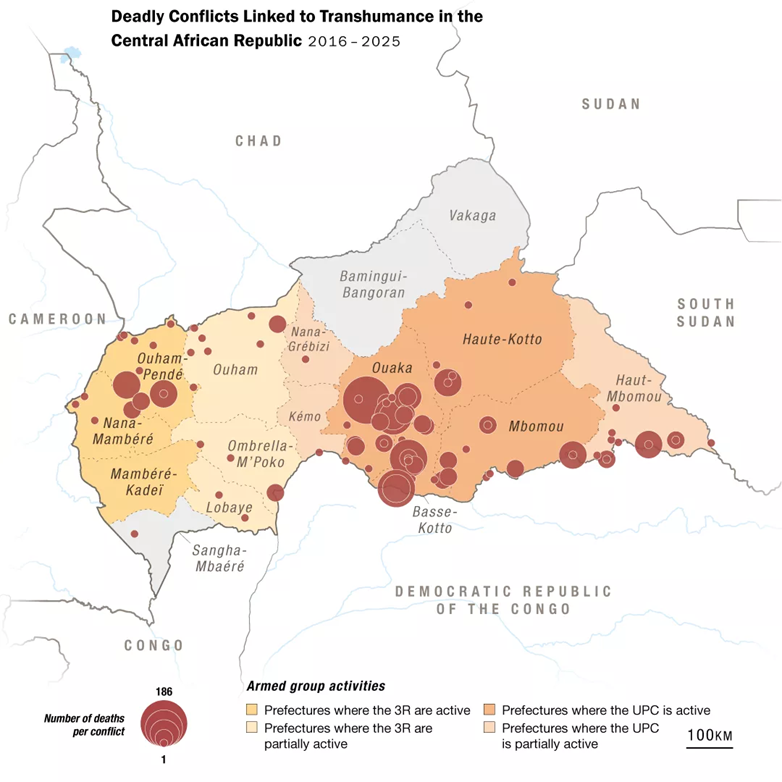

Another wave of violence was launched in January 2023 when CPC fighters attacked FACA using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and armed drones.10International Crisis Group, ‘Ten Years after the Coup, Is the Central African Republic Facing Another Major Crisis?’, Q&A with Enrica Picco, 22 March 2023. This conflict has evolved to include a struggle for control over mining sites and transhumance corridors (traditional pastoral paths of herders).

Key Events Since 1 July 2024

During the reporting period, five NIACs on the territory of CAR involved the State armed forces fighting an organized non-State armed group. FACA have received military support from the Wagner Group since 2018, and, since late 2020, by the RDF.11Rwandan Ministry of Defence, ‘Rwanda deploys force protection troops to Central African Republic’, Statement, Ref RDF/MPR/A/07/12/20, Kigali, 20 December 2020. See also International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic’, Africa Briefing No 191, 7 July 2023. A CPC splinter group, the Coalition pour le Changement Fondamental (CPC-F) has, since September 2024, been engaged in a low-intensity NIAC with CAR.12‘RCA: la CPC change de nom, se sépare de Bozizé et définit de nouveaux objectifs’, RFI, 4 September 2024. A sixth NIAC was being fought between two organized non-State armed groups. Parties to the five conflicts have committed serious violations of IHL against both Christian and Muslim communities.

On 30 July 2024, the UN Security Council lifted the arms embargo on the CAR authorities that had been in place since 2013.13‘Peace and security in Africa’, UN Security Council Resolution 2745, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 30 July 2024, operative para 1. Progress has been made in reducing the level of armed violence across much of the country. As of June 2025, while security remained fragile in the west and east of the country, fewer incidents were recorded in the centre. Speaking for the RDF, Brigadier General Ronald Rwivanga described the overall situation as ‘relatively calm’, even claiming: ‘We successfully repelled the rebels’.14‘Rwandan Forces Step in Where Others Step Out’, African Defense Forum, 17 June 2025. But armed groups continue to attack civilians, and in the north-east, armed incursions were linked to the armed conflict in neighbouring Sudan, with suspected Rapid Support Forces (RSF) vehicles sighted in Am Dafok and Aouk in Vakaga prefecture. The UN Secretary-General warned the Security Council in June 2025 that spillover from the conflict in Sudan continued to fuel insecurity there.15‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, 13 June 2025, paras 23, 32.

Another armed group that formed in 2023 in eastern CAR, Azande Ani Kpi Gbe (‘Too many Azande people have died’), fought against the Unité pour la paix en Centrafrique (UPC), a group formed in 2014 from former Séléka forces. AAKG has targeted Muslim and Fulani communities in the region, abducting civilians and repeatedly engaging in acts of sexual violence, including the perpetration of gang rapes.16‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2023/769, 16 October 2023, paras 25 and 40. In 2024, hundreds of AAKG fighters were integrated into FACA although a rump force remained.17Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central African Republic: Populations in the Central African Republic are at risk of atrocity crimes due to ongoing violence by armed groups and abuses by government and allied forces’, 15 July 2025.

Wagner Ti Azande (WTA), which is also fighting the UPC in the east of the country, has strong ‘ties’ to FACA but does not in practice operate under its effective control.18OHCHR, ‘Central African Republic: UN report calls for accountability for attacks by armed groups active in Haut Oubangui’, Press release, Geneva, 5 March 2025. Indeed, the United Nations has observed that while ‘integrated’ into FACA, the armed forces’ control over the WTA ‘remains loose’ and it ‘often defies the command of the FACA’.19UN, ‘Background Note – The situation in the Haut-Mbomou Prefecture ASG PBSO Visit to the Central African Republic’, March 2025, https://bit.ly/49Fz4jt, p 2. The group gained its moniker from the fact that its Azande membership were trained by the Wagner Group. The WTA is sometimes described as nothing more than a rebranding of the AAKG,20F. Zeguino, ‘Wagner ti Azandé, c’est le nom de la nouvelle milice de Touadera à Obo’, Corbeau News Centrafrique, 2 May 2024. but in reality stands separate from it. The two groups even mounted joint military operations during the reporting period.21OHCHR, ‘Central African Republic: UN report calls for accountability for attacks by armed groups active in Haut Oubangui’.

On 23 April 2025, President Touadéra announced that the leaders of Retour, Réclamation et Réhabilitation (3R), a group formed in CAR’s north-west in 2015 to protect Fulani herders from attacks by Anti-Balaka militia, and the UPC had both committed to lay down their arms and rejoin the 2019 Political Agreement. The agreement, which followed discussions in N’Djamena facilitated by the Chadian government,22Herds coming from Chad account for around 70% of livestock arriving in CAR. This issue has been a source of conflict. To better manage the movement of livestock, the two nations signed agreements in 2012 and 2019, but these are still to be effectively implemented. In January 2025, however, they created a joint force to guard the border. International Crisis Group, ‘Violence and Herding in the Central African Republic: Time to Act’, Africa Report No 317, 28 May 2025. provided for a ceasefire, the dissolution of the two armed groups, and the establishment of cantonment sites for DDR.23‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 10.

On 10 July 2025, Ali Darassa, the founder of UPC, and Sembé Bobo, the commander of 3R, duly announced the disbanding of their respective movements. But while this is undoubtedly a major symbolic step, as the International Crisis Group has cautioned, this may not translate into an end to the hostilities, as thousands of fighters across the country may refuse to demobilize in the absence of a ‘credible’ DDR process.24Crisis Watch, ‘Central African Republic’, International Crisis Group, July 2025.

The Humanitarian Situation

Violence, while lessening at the time of writing, still affected 2.8 million people – half of CAR’s total population. In particular, tensions escalated around mining sites and transhumance corridors (seasonal areas of grazing) with clashes between transhumant herders and 3R fighters, and involved killings, sexual violence, kidnappings, and forced displacement of civilians.25Ibid, para 24. As the UPC and 3R comprise mainly herders, this has accentuated the government’s ‘tendency’ to ‘conflate pastoralists with insurgents’.26International Crisis Group, ‘Violence and Herding in the Central African Republic: Time to Act’. The United Nations reports that one in every five Central African remains displaced either within the country or abroad, mainly in neighbouring countries because of conflict, violence, lack of essential services and extreme weather events. IHL and human rights violations and extreme weather events such as floods continue to lead to new displacements. About thirty-eight per cent of the population are vulnerable to the point that humanitarian aid alone is not enough to sustain them.27OCHA, ‘Central African Republic’, accessed 1 January 2026.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

Six non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) occurred in CAR throughout the review period, including one between two non-State armed groups:

- CAR (supported by Wagner Group/Africa Corps and the RDF) v UPC

- CAR (supported by Wagner Group/Africa Corps and the RDF) v 3R

- CAR (supported by Wagner Group/Africa Corps and the RDF) v CPC-F

- CAR (supported by Wagner Group/Africa Corps and the RDF) v CPC

- CAR (supported by Wagner Group/Africa Corps and the RDF) v AAKG (supported by WTA elements)

- UPC v AAKG.

The conflicts are all regulated by Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and customary IHL. CAR is also a State Party to Additional Protocol II of 1977, but none of the NIACs between FACA and the five non-State armed groups meets the additional requirements of Article 1(1) of the Protocol – specifically the need for a level of territorial control that would enable the groups to sustain military operations and implement the Protocol. The NIAC between the AAKG and the UPC cannot be regulated by Additional Protocol II as the Protocol requires one of the parties to be the territorial State.28The Protocol applies to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups’. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II.

Criminal responsibility for international crimes

CAR is a State Party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which it ratified in 2001.29Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002 (hereafter, ICC Statute). All events covered in this report therefore potentially fall within the Court’s material jurisdiction. In 2022, however, following a referral by the CAR government eight years earlier, the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC ended its investigation into alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes committed since 1 August 2012 by the Séléka and Anti-Balaka armed groups.30ICC, ‘The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Karim A.A. Khan KC, announces conclusion of the investigation phase in the Situation in the Central African Republic’, Statement, 16 December 2022.

Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo, the President and Commander-in-Chief of the Mouvement de libération du Congo, was charged with crimes against humanity (murder and rape) and war crimes (murder, rape, and pillage), which he was accused of committing in CAR in 2002–03. In 2018, the ICC Appeals Chamber decided, by majority, to acquit Mr Bemba Gombo of all charges.31ICC, ‘Bemba Case’, accessed 3 November 2025.

On 24 July 2025, the trial of Anti-Balaka leaders Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona and Alfred Yékatom, who were accused of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity in Bangui and western CAR between September 2013 and at least February 2014, concluded with their conviction on multiple counts. Mr Yekatom was sentenced to fifteen years in prison and Mr Ngaïssona to twelve years. On 26 September, the Defence Team for the two men, along with the Office of the Prosecutor, filed notices of appeal.32ICC, ‘Yekatom and Ngaïssona Case’, accessed 4 November 2025.

At the time of writing, the trial of Seleka commander Mahamat Said Abdel Kani, who is accused of committing war crimes (torture, cruel treatment, and outrages upon personal dignity) and crimes against humanity (severe deprivation of liberty, torture, persecution, and other inhumane acts) in Bangui in 2013, was coming to a conclusion. Closing statements took place on 25 and 26 November 2025 since which the judges have been deliberating.33ICC, ‘Said Case’, accessed 30 November 2025.

The Special Criminal Court

The Special Criminal Court (SCC), inaugurated in Bangui in 2018, is a court for the prosecution of international crimes. The SCC is part of the domestic criminal justice system in CAR, but is staffed by international as well as national experts. In April 2024, the Court issued an arrest warrant for former president François Bozizé. He is charged with the commission of crimes against between 2009 and 2013 by the Presidential Guard and other security services at the Bossembélé military training centre located to the north of Bangui. In September 2024, the SCC referred the case against Mr Bozizé to the Court’s Trial Chamber. Mr Bozizé fled from CAR in 2013, returning six years later as CPC leader before going into hiding in Guinea-Bissau, where he is said to be now. According to the SCC’s rules of procedure, he can be tried in absentia.34Ibid.

In June 2024, a former Anti-Balaka leader, Edmond Beïna, was arrested on charges of crimes against humanity and war crimes allegedly committed in 2014 in Djomo, Gadzi and Guen in Mambéré-Kadéï province in the south-west. In November 2024, the ICC made public its issuance of an arrest warrant for Mr Beïna in 2018. The CAR government has challenged the ICC’s jurisdiction on the grounds that the same case is being prosecuted in CAR.35Ibid. In September 2025, the ICC declared it was established that the case against Mr Beïna was ‘genuinely being prosecuted at the domestic level’ and, therefore, the case must be declared inadmissible before the ICC.36ICC, ‘Decision on the Central African Republic’s challenge to the admissibility of the case against Edmond Beina’ (Pre-Trial Chamber II) (Case No ICC-01/14), 12 September 2025, para 43 et seq.

A year earlier, Abakar Zakaria Hamid, a former Seleka leader, was arrested and charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes linked to a 2014 attack at the Notre-Dame church in Bangui, which was being used at the time as a camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs).37Human Rights Watch, ‘Central African Republic: Events of 2024’, 2025.

At the time of writing, however, the future of the SCC was highly uncertain owing to lack of funding. In October 2025, Amnesty International warned that its closure would be ‘a catastrophic blow to thousands of victims’ and survivors’ prospects of securing justice’. Amnesty called on the African Union and the European Union, and their Member States, to ‘step up’ by providing sustained funding and human resources support.38Amnesty International, ‘CAR: Urgent financial support needed to prevent catastrophic closure of Special Criminal Court’, 17 October 2025.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

The period under review continued to see serious violations of the IHL rules protecting civilians across CAR. In his June 2025 report to the UN Security Council, the UN Secretary-General condemned the ‘persistent’ violations of IHL, singling out sexual violence, whose continued perpetration he described as being ‘of grave concern’.39‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 75.

Civilian Objects Under Attack

Under customary IHL, attacks may only be directed against military objectives. Attacks must not be directed against civilian objects.40International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives41ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. and, as such, are protected against attack.42ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 10: ‘Civilian Objects’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

Attacks against livestock

Since 2014, the International Crisis Group has repeatedly emphasized the critical need to reduce violence between herders and farmers in order to stabilize the situation in CAR. A further concern is cattle rustling by FACA troops. Since 2021, as the army regained control of the countryside with the support of the Wagner Group and the RDF, FACA soldiers organized cattle-rustling networks

similar to those the armed groups had run near the traditional herding corridors. The ensuing theft led pastoralists to abandon these routes, driving their cattle instead through farmers’ fields, which made them vulnerable to reprisal. Herders have accordingly lost what little confidence they had left in the State, increasingly looking to the militias for protection.44International Crisis Group, ‘Violence and Herding in the Central African Republic: Time to Act’.

Under IHL, livestock are civilian objects protected from attack.45ICRC Commentary on Article 52 of Additional Protocol I of 1977, 1987, para 2008; A. Bellal and S. Casey-Maslen, The Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions in Context, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2022, para 8.7 and note 18. Cattle may also be considered objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population.46ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 54: ‘Attacks against Objects Indispensable to the Survival of the Civilian Population.

Attacks against humanitarian aid

There were a number of attacks on convoys seeking to provide desperately needed humanitarian aid to remote communities during the reporting period. In late March 2025, for instance, gunmen attacked a humanitarian convoy near Zemio town in Haut-Mbomou prefecture, killing one NGO worker and three ethnic Fulani civilians.47Crisis Watch, ‘Central African Republic’, International Crisis Group, April 2025. Under IHL, parties to armed conflicts are obliged to facilitate the delivery of impartial humanitarian assistance.48ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’. Attacks on MINUSCA, which is not party to any of the armed conflicts in CAR, may amount to a war crime.49MINUSCA, ‘La MINUSCA condamne l’attaque meurtrière contre des Casques bleus dans le Haut-Mbomou’, Press release, 29 March 2025.

Civilians Under Attack

Under customary IHL, civilians enjoy general protection from the effects of hostilities, unless and for such time as they directly participate in hostilities.50ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Accordingly, parties to armed conflicts must at all times distinguish between combatants and civilians, and are prohibited from directing attacks against civilians.51ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants. In case of doubt, persons should be treated as civilians.52 ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. The accompanying commentary states that in NIACs, ‘the issue of doubt has hardly been addressed in State practice, even though a clear rule on this subject would be desirable as it would enhance the protection of the civilian population against attack.’ One ‘cannot automatically attack anyone who might appear dubious….’ The same approach with respect to IACs ‘seems justified’ in NIACs. Civilians may be incidentally affected by attacks against lawful targets. Such attacks must, however, be proportionate, and the attacker must take all feasible precautions to avoid or at least minimize incidental civilian deaths and injuries (and damage to civilian objects).

Attacks directed against civilians

Civilians were deliberately targeted by the parties to the armed conflicts during the reporting period in violation of IHL. In the south-east, new violence erupted in Haut-Mbomou and Mbomou prefectures in the second half of 2024. Both the AAKG, which is based in the south-east of CAR, and the UPC, a member of the CPC coalition, attacked civilians. The AAKG targeted Muslims presumed to be sympathetic to the UPC,53Human Rights Watch, ‘Central African Republic: Events of 2024’. while 3R attacked civilians outside towns along the north-west border with Cameroon. In July 2024, 3R reportedly killed at least a dozen civilians outside Bocaranga. This followed the summary execution of at least sixteen farmers outside Bohong three months earlier.54Ibid.

WTA and AAKG fighters repeatedly targeted civilians over their alleged association with UPC and the Muslim community. From 1 to 7 October 2024, WTA and AAKG fighters committed atrocities against civilians in Dembia and Rafai, targeting, in particular, Muslim and Fulani communities as well as Sudanese asylum-seekers. In total, they murdered fourteen people and raped twenty-one women.55‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/97, 14 February 2025, para 34.

On 25 November, near Kopia village in Ouaka prefecture, suspected UPC fighters killed ten motorcycle taxi drivers and passengers.56Ibid, para 30. Attacks by 3R fighters in Lim-Pendé prefecture in the north-west between 25 and 28 February 2025 resulted in thirteen civilian deaths and the burning of hundreds of homes. In Nana-Mambéré and Mambéré-Kadéï prefectures, Anti-Balaka and 3R fighters killed, kidnapped, or extorted civilians around mining sites and transhumance corridors.57‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 26.

Use of improvised explosive devices

Throughout the reporting period, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) continued to pose a threat to civilians in CAR.58‘UNODC Supports Raising Community Awareness of the Risks Associated with Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in Niger’, UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), April 2025. CAR is a State Party to the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, which prohibits FACA from using any anti-personnel mine, defined as a munition (including IEDs) that is designed or adapted to be activated by a person. This disarmament treaty does not, however, bind non-State armed groups directly under international law. CAR is not a State Party to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons whose Amended Protocol II of 1996 on landmines and booby-traps, binds all parties to an armed conflict, including non-State armed groups.59Art 1(2), Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998.

Nevertheless, all armed groups that are party to an armed conflict are subject to the customary IHL principles of distinction and proportionality in attack, underpinned by the duty to take precautions to protect civilians. Customary law further requires that when landmines are used, ‘particular care must be taken to minimize their indiscriminate effects.’60ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 81: ‘Restrictions on the Use of Landmines’. When deployed in populated areas or locations frequently accessed by civilians, these devices may often have such effects.61ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’; and Rule 12: ‘Definition of Indiscriminate Attacks’. That said, use of IEDs by non-State armed groups in CAR did not result – at least in 2024 – in significant contamination by improvised anti-personnel mines.62Mine Action Review, ‘Central African Republic’, in Clearing the Mines 2025, Report, Norwegian People’s Aid, London, November 2025.

Forced displacement

Considerable forced displacement in CAR over the past decade is linked to the multiple armed conflicts on its territory. On 26 July 2024, the Prime Minister of CAR and the UN Secretary-General’s Special Adviser on Solutions to Internal Displacement launched the national strategy for durable solutions for IDPs and returnees in the Central African Republic 2024–2028. In rare, good news, reflecting the reduction in violence in certain areas of the country, 117,936 of 455,533 registered IDPs returned to their homes between January and October 2024.63‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/730, 11 October 2024, para 55.

Under customary IHL, parties to any armed conflict are prohibited from ordering the displacement of the civilian population in relation to the conflict unless it is required for their security or for imperative military reasons.64ICRC, Customary IHL 129: ‘The Act of Displacement’. Breaches of these prohibitions may be war crimes.65ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. Any displacement must be temporary, with all possible measures taken to ensure proper shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition and that members of the same family are not separated.66ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 131: ‘Treatment of Displaced Persons’. The prohibition aims to protect civilian populations from arbitrary or punitive displacement and to uphold their rights to remain in or return to their homes.67ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Ennemy

Customary and treaty IHL provide fundamental guarantees for anyone in the power of a party to a conflict, prohibiting acts such as torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, collective punishments, sexual violence, enforced disappearance, and unfair trials. Special protection is afforded to civilians who face a specific risk of harm, such as women, children, refugees, and IDPs.68ICRC, Customary IHL Rules 134–138: ‘Chapter 39. Other Persons Afforded Specific Protection’.

Conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence

Rape and other forms of sexual violence in connection with armed conflict are prohibited and constitute war crimes.69ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. The conflicts in CAR have been marked by gender-based violence, with women and girls regularly targeted. For 2024, the United Nations recorded acts of sexual violence against more than 200 girls, with most of these war crimes attributed to the CPC (58 cases), followed by the UPC (26 cases), and 3R (22 cases).70‘Children and armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 30. The United Nations stated that between October 2024 and February 2025, while conflict-related sexual violence persisted throughout the country, it was most prevalent in Lim-Pendé prefecture, where it was said to be perpetrated primarily by 3R fighters.71‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/97, 14 February 2025, para 43.

A wave of sexual violence was seen in the first week of October 2024 also in Mbomou prefecture, with WTA fighters targeting mainly the Fulani community and other Muslims, as well as a camp for Sudanese refugees and asylum-seekers. MINUSCA documented the rape of fourteen women and seven girls aged between twelve and seventeen years during the assault, many of whom were gang-raped. In addition, two girls and one woman were sexually enslaved while one woman was forced into marriage.72MINUSCA and OHCHR, ‘Rapport public sur les violations et atteintes graves aux droits de l’homme commises par les Wagner Ti Azandé et les Azandé Ani Kpi Gbé du 1 au 7 octobre 2024 à Dembia et Rafaï, préfecture du Mbomou’, Report, March 2025, para 39. None of the victims received adequate medical assistance, either through fear of being stigmatized or due to lack of medicine and rape kits in local hospitals.73Ibid, para 42.

Protection of children

Under IHL, children are afforded special protection in armed conflicts, recognizing their particular vulnerability. Core rules prohibit the recruitment and use of children under the age of fifteen years in hostilities, whether in State armed forces or non-State armed groups, and forbid their participation in combat.74ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 136: ‘Recruitment of Child Soldiers’. Children are entitled to general protection as civilians, including against direct attack, arbitrary detention, sexual violence, and ill-treatment. If detained, they must be held separately from adults (unless with their family) and treated in a manner appropriate to their age. Evacuation and reunification of separated children with their families are also prioritized.75ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 135: ‘Children’.

During the reporting period, children continued to be disproportionately affected by the ongoing hostilities in CAR. For 2024, the United Nations verified 733 grave violations against 479 children (283 boys, 196 girls).76‘Children and armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, para 26. A total of 331 children (238 boys, 93 girls) were recruited and used by armed groups, with the CPC responsible for 191 of these victims, the UPC for 123, and the AAKG for 70. At least fifty-one children are said to have served in combat roles with armed groups.77Ibid, para 27.

Treatment of persons detained in relation to an armed conflict

At the end of 2023, 1,749 detainees were awaiting trial, some of whom had been held for almost six years without trial.78Agence France-Presse, ‘L’ONU dénonce les violations des droits humains dans les prisons centrafricaines’, Voice of America, 18 July 2024. It is not known how many were being detained in relation to the conflicts but ethnic and religious minorities have been disproportionately targeted for arbitrary arrest and detention in operations by FACA and its Wagner Group/Africa Corps allies.79Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central African Republic’, 15 July 2025. Moreover, after the years of armed conflict and violence that have blighted the country, the judicial and prison systems in CAR have either been completely destroyed or severely weakened. Where they still exist, prisons suffer from extreme overcrowding, food shortages – sometimes leading to deaths from malnutrition – and a lack of adequate medical care and environmental hygiene.80MINUSCA, ‘Affaires judiciaires et pénitentiaires’, 2024.

As MINUSCA further recalls, the establishment of functioning courts and prisons is essential. Its Judicial and Penitentiary Section continues to support reform of the prison system with a view to ensuring its ‘compliance with international standards and practices in prison administration’. Currently, there is a heightened risk of security incidents, mass escapes, and infectious diseases. The situation is particularly critical at Ngaragba Central Prison, which has for a long time hosted three times its official capacity of 382 inmates.81Ibid. By May 2025, the figure was said to have risen further.82UN Peacekeeping, ‘Des prisons au service d’une paix durable’, 8 May 2025. This was despite the opening in January of a prison block for high-security detainees.83UNDP, ‘RCA: remise officielle du nouveau bloc de détention de la Maison d’arrêt centrale de Ngaragba par la MINUSCA et le PNUD’, 8 January 2025.

- 1International Commission of Inquiry on the Central African Republic, Final Report, UN Doc S/2014/928, 22 December 2014.

- 2UN Security Council Resolution 2149, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 10 April 2014, operative para 18.

- 3See MINUSCA, ‘Mandate’. As of 1 June 2025, the Mission’s deployed military component totalled 14,054 troops. ‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 61. Under its Resolution 2759, the UN Security Council extended MINUSCA’s mandate until 15 November 2025. UN Security Council Resolution 2759, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 14 November 2024, operative para 32. Operative para 28 of Resolution 2800, adopted on 13 November 2025 by fourteen votes to nil with one abstention (the United States), extended the mission’s mandate until 15 November 2026.

- 4L’Accord politique pour la paix et la réconciliation en République centrafricaine, UN Doc S/2019/145, 15 February 2019.

- 5‘Russia Pushes CAR to Choose Africa Corps Over Wagner Mercenaries’, Africa Defense Forum, 28 October 2025.

- 6MINUSCA and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘Rapport public sur les violations des droits de I’Homme et du droit international humanitaire en République centrafricaine durant la période électorale, Juillet 2020–Juin 2021’, Report, p 4.

- 7MINUSCA and OHCHR, ‘Rapport public sur les violations des droits de I’Homme’. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), as of May 2024, 750,000 Central African citizens were seeking refuge abroad and 451,000 persons were internally displaced. OCHA, ‘Central African Republic: Situation Report’, 11 December 2024.

- 8Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), ‘Wagner Group Operations in Africa: Civilian Targeting Trends in the Central African Republic and Mali’, 30 August 2022.

- 9S. Ritter, ‘The New “Africa Corps”: Russia’s Wagner Rebranding’, Energy Intelligence, 24 May 2024, http://bit.ly/4hesCSg.

- 10International Crisis Group, ‘Ten Years after the Coup, Is the Central African Republic Facing Another Major Crisis?’, Q&A with Enrica Picco, 22 March 2023.

- 11Rwandan Ministry of Defence, ‘Rwanda deploys force protection troops to Central African Republic’, Statement, Ref RDF/MPR/A/07/12/20, Kigali, 20 December 2020. See also International Crisis Group, ‘Rwanda’s Growing Role in the Central African Republic’, Africa Briefing No 191, 7 July 2023.

- 12‘RCA: la CPC change de nom, se sépare de Bozizé et définit de nouveaux objectifs’, RFI, 4 September 2024.

- 13‘Peace and security in Africa’, UN Security Council Resolution 2745, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 30 July 2024, operative para 1.

- 14‘Rwandan Forces Step in Where Others Step Out’, African Defense Forum, 17 June 2025.

- 15‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, 13 June 2025, paras 23, 32.

- 16‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2023/769, 16 October 2023, paras 25 and 40.

- 17Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central African Republic: Populations in the Central African Republic are at risk of atrocity crimes due to ongoing violence by armed groups and abuses by government and allied forces’, 15 July 2025.

- 18OHCHR, ‘Central African Republic: UN report calls for accountability for attacks by armed groups active in Haut Oubangui’, Press release, Geneva, 5 March 2025.

- 19UN, ‘Background Note – The situation in the Haut-Mbomou Prefecture ASG PBSO Visit to the Central African Republic’, March 2025, https://bit.ly/49Fz4jt, p 2.

- 20F. Zeguino, ‘Wagner ti Azandé, c’est le nom de la nouvelle milice de Touadera à Obo’, Corbeau News Centrafrique, 2 May 2024.

- 21OHCHR, ‘Central African Republic: UN report calls for accountability for attacks by armed groups active in Haut Oubangui’.

- 22Herds coming from Chad account for around 70% of livestock arriving in CAR. This issue has been a source of conflict. To better manage the movement of livestock, the two nations signed agreements in 2012 and 2019, but these are still to be effectively implemented. In January 2025, however, they created a joint force to guard the border. International Crisis Group, ‘Violence and Herding in the Central African Republic: Time to Act’, Africa Report No 317, 28 May 2025.

- 23‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 10.

- 24Crisis Watch, ‘Central African Republic’, International Crisis Group, July 2025.

- 25Ibid, para 24.

- 26International Crisis Group, ‘Violence and Herding in the Central African Republic: Time to Act’.

- 27OCHA, ‘Central African Republic’, accessed 1 January 2026.

- 28The Protocol applies to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups’. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II.

- 29Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002 (hereafter, ICC Statute).

- 30

- 31ICC, ‘Bemba Case’, accessed 3 November 2025.

- 32ICC, ‘Yekatom and Ngaïssona Case’, accessed 4 November 2025.

- 33ICC, ‘Said Case’, accessed 30 November 2025.

- 34Ibid.

- 35Ibid.

- 36ICC, ‘Decision on the Central African Republic’s challenge to the admissibility of the case against Edmond Beina’ (Pre-Trial Chamber II) (Case No ICC-01/14), 12 September 2025, para 43 et seq.

- 37Human Rights Watch, ‘Central African Republic: Events of 2024’, 2025.

- 38Amnesty International, ‘CAR: Urgent financial support needed to prevent catastrophic closure of Special Criminal Court’, 17 October 2025.

- 39‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 75.

- 40International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 41

- 42

- 43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

- 44International Crisis Group, ‘Violence and Herding in the Central African Republic: Time to Act’.

- 45ICRC Commentary on Article 52 of Additional Protocol I of 1977, 1987, para 2008; A. Bellal and S. Casey-Maslen, The Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions in Context, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2022, para 8.7 and note 18.

- 46ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 54: ‘Attacks against Objects Indispensable to the Survival of the Civilian Population.

- 47Crisis Watch, ‘Central African Republic’, International Crisis Group, April 2025.

- 48

- 49MINUSCA, ‘La MINUSCA condamne l’attaque meurtrière contre des Casques bleus dans le Haut-Mbomou’, Press release, 29 March 2025.

- 50

- 51

- 52ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. The accompanying commentary states that in NIACs, ‘the issue of doubt has hardly been addressed in State practice, even though a clear rule on this subject would be desirable as it would enhance the protection of the civilian population against attack.’ One ‘cannot automatically attack anyone who might appear dubious….’ The same approach with respect to IACs ‘seems justified’ in NIACs.

- 53Human Rights Watch, ‘Central African Republic: Events of 2024’.

- 54Ibid.

- 55‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/97, 14 February 2025, para 34.

- 56Ibid, para 30.

- 57‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/383, para 26.

- 58‘UNODC Supports Raising Community Awareness of the Risks Associated with Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in Niger’, UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), April 2025.

- 59Art 1(2), Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998.

- 60

- 61ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’; and Rule 12: ‘Definition of Indiscriminate Attacks’.

- 62Mine Action Review, ‘Central African Republic’, in Clearing the Mines 2025, Report, Norwegian People’s Aid, London, November 2025.

- 63‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/730, 11 October 2024, para 55.

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 70‘Children and armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 30.

- 71‘Central African Republic, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/97, 14 February 2025, para 43.

- 72MINUSCA and OHCHR, ‘Rapport public sur les violations et atteintes graves aux droits de l’homme commises par les Wagner Ti Azandé et les Azandé Ani Kpi Gbé du 1 au 7 octobre 2024 à Dembia et Rafaï, préfecture du Mbomou’, Report, March 2025, para 39.

- 73Ibid, para 42.

- 74

- 75

- 76‘Children and armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, para 26.

- 77Ibid, para 27.

- 78Agence France-Presse, ‘L’ONU dénonce les violations des droits humains dans les prisons centrafricaines’, Voice of America, 18 July 2024.

- 79Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central African Republic’, 15 July 2025.

- 80MINUSCA, ‘Affaires judiciaires et pénitentiaires’, 2024.

- 81Ibid.

- 82UN Peacekeeping, ‘Des prisons au service d’une paix durable’, 8 May 2025.

- 83