Conflict Overview

Since 1996, conflict in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has caused approximately six million deaths.1Center for Preventive Action, ‘Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, Council for Foreign Relations, Updated 16 December 2025. The First Congo War (1996–97) broke out in the wake of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, following which some two million Hutus crossed into the DRC (then known as Zaire). Those who settled in refugee camps in the provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu included Hutu extremists responsible for the genocide. Rwandan troops under President Paul Kagame and Tutsi militias in the DRC operating with his support invaded Zaire, which was then ruled by Mobutu Sese Seko. After defeating Mobutu, DRC opposition leader Laurent Kabila was made president. President Kabila decided to change the country’s name back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Second Congo War began in 1998 following a deterioration of relations with Rwanda. President Kabila ordered all foreign troops out of the country and allowed Hutu armed groups to organize at the border once again. Rwanda invaded in 1998. Laurent Kabila was assassinated in a 2001 coup attempt but his son, Joseph Kabila, seized power. The Second Congo War is considered the deadliest since the Second World War, with an estimated death toll of three million.

Among many armed groups to emerge in the early 2000s was the March 23 Movement (M23), which was composed mainly of ethnic Tutsis. In 2013, the United Nations (UN) Security Council authorized a brigade of the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) to support the Congolese Armed Forces (FARDC) in their fight against M23. M23 stopped fighting in 2013.

Félix Tshisekedi was controversially declared the winner of the DRC’s presidential elections of December 2018 – with evidence that another candidate had actually won more votes – although the handover from President Kabila marked the first peaceful transfer of power in the history of the DRC. President Tshisekedi had to confront outbreaks of Ebola virus and the continuing violence in the east, which was spurred by the abundant presence of natural resources, especially precious minerals. In 2022, M23 rebels resurfaced, seizing control of large parts of North Kivu province by July 2023.

Key events since July 2024

The DRC, the second largest country in Africa, had five non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) on its territory during the reporting period. Two involve the State armed forces – the FARDC – fighting a non-State armed group, namely, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the Cooperative for Development of the Congo (CODECO). A third NIAC is being fought between the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) and CODECO. The two other NIACs involve one organized armed group fighting another: CODECO against Zaïre; and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) against M23.

In addition, and despite its consistent denials,2Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, Geneva, 5 September 2025, para 8. See also: Letter dated 10 June 2022 from the Group of Experts extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2582 (2021) addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2022/479, 14 June 2022, Annex 39. Rwanda exerts a level of control over the Mouvement du 23 mars (M23)3See eg: Letter dated 3 July 2025 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/446, 3 July 2025, paras 44, 45. Shortly after its creation in 2012, M23 rapidly gained territory and seized Goma – acts that saw accusations of war crimes and human rights abuses. After being forced to withdraw from Goma, the group suffered a series of heavy defeats at the hands of the DRC army along with a UN force that saw it expelled from the country. M23 fighters agreed to be integrated into the army in return for promises that Tutsis would be protected. But in 2021, the group took up arms again, saying the promises had been broken. The group take its name from a peace agreement that was signed with a previous Tutsi-led rebel group on 23 March 2009. D. Zane and W. Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What is the fighting about and is Rwanda involved?’, BBC, 27 January 2025 (Updated 1 July 2025). such that the NIAC between the DRC and M23 is also an international armed conflict (IAC) under international humanitarian law (IHL).4International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), Prosecutor v Tadić(aka ‘Dule’), Judgment (Appeals Chamber) (Case No IT-94-1-A), 15 July 1999, para 131; International Criminal Court, Prosecutor v Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, Judgment (Trial Chamber I) (Case No ICC-01/04-01/06), 14 March 2012, para 541; Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 20. Control over M23, a group led mostly by Congolese Tutsis and which operates under the umbrella of the ‘Alliance Fleuve Congo’ (AFC),5K. Diya (a pseudonym), ‘The M23 takeover, part 1: In DR Congo’s Walikale, forced labour and fears of arrest’, The New Humanitarian, 1 October 2025. has been buttressed by the presence of Rwandan regular forces in the eastern DRC.6E. Makumeno, ‘Second DR Congo city falls to Rwanda-backed rebels’, BBC, 16 February 2025. These regions are rich in minerals, particularly gold, tin, tantalum, and tungsten.7Zane and Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What’s the fighting in DR Congo all about?; Panzi, ‘Where Minerals Are Found in the DRC’, 2024. More than 120 armed groups are engaged in violence in the provinces of North and South Kivu and Ituri.8‘RDC: au moins 55 morts dans une attaque de la CODECO’, Africanews.fr, 11 February 2025.

On 27 January 2025, M23 seized control of the city of Goma in eastern DRC, the provincial capital of mineral-rich North Kivu, following a ‘coordinated offensive’ with Rwandan troops. M23 and RDF troops entered Goma on multiple fronts, sparking intense clashes and heavy artillery exchanges.9Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 12. On 16 February, M23 took Bukavu, the provincial capital of South Kivu and second largest city in the east.10Ibid, paras 26, 30–34, 42–43, 49–50, 55–56, 59. The group then captured Walikale, a mining hub in North Kivu, on 19 March 2025 – the farthest west they have ever reached. M23 later said they would withdraw from the town in a ‘gesture of peace’.11M. Ali, ‘Mapping the human toll of the conflict in DR Congo’, Explainer, Al Jazeera, 24 March 2025; ‘DRC M23 rebels to withdraw from Walikale in peace gesture’, Al Jazeera, 22 March 2025. They made good on the pledge in early April 2025.12‘Congo rebels leave strategic town ahead of planned Doha talks’, Reuters, 4 April 2025.

In September 2025, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) issued a report on the hostilities against M23 and the subsequent occupation. The fact-finding mission, which was established pursuant to a February 2025 Human Rights Council resolution,13Human Rights Council Resolution S-37/1; adopted without a vote on 7 February 2025. concluded that between January and July 2025, all parties to the conflicts committed serious violations of international law that may constitute international crimes. The mission recommended the prompt establishment of a formal commission of inquiry, as the Council resolution had mandated.14Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 93.

Attempts to broker a sustained peace between the DRC and Rwanda have so far proved unsuccessful. A ceasefire agreed upon in July 2024 following Angolan mediation did not hold, although at a meeting a month later in Rubavu in Rwanda, officials discussed the neutralization of the FDLR and the withdrawal of Rwandan forces as the basis for a durable peace.15P. Asanzi, ‘The revived Luanda Process – inching towards peace in east DRC?’, Institute for Security Studies, 21 October 2024. Nevertheless, on 29 August 2024, DRC launched proceedings against Rwanda in the East African Court of Justice, alleging violations of its sovereignty and the perpetration of crimes against civilians.16East African Court of Justice, ‘Court Hears Applications Arising From Case Filed by DRC Against Rwanda Over Alleged Conflicts in North Kivu Region’, Arusha, 27 September 2024.

On 14 October 2024, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court announced renewed investigations into possible crimes committed in North Kivu since January 2022.17ICC, ‘Statement of ICC Prosecutor Karim A. A. Khan KC on the Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and renewed investigations’, Press release, 14 October 2024. Operations by M23 and the RDF in Kalehe territory in South Kivu between December 2024 and January 2025 prompted deployment to the DRC of the Burundi army, the Force de Défense Nationale du Burundi (FDNB), which occurred with the consent of the DRC government.18‘Burundi warns Rwanda as eastern DR Congo conflict advances’, RFI, 12 February 2025.

On 27 June 2025, the ministers for foreign affairs of the DRC and Rwanda signed a peace agreement brokered by the United States and Qatar in Washington, DC. The deal demands the ‘disengagement, disarmament and conditional integration’ of armed groups fighting in eastern DRC and the withdrawal of the RDF from Congolese territory. By signing the Washington peace agreement, it has become more difficult for Rwanda to deny its involvement in the conflict.19Zane and Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What is the fighting about and is Rwanda involved?’. Former Congolese president Joseph Kabila (who has been sentenced to death in absentia by a DRC military court for crimes against the DRC),20S. Lawal, ‘Kabila sentenced to death: What it means for DRC and what’s next’, Explainer, Al Jazeera, 2 October 2025. derided the peace deal as ‘nothing more than a trade agreement’.21P. Nije, ‘DR Congo-Rwanda peace deal met with scepticism in rebel-held city’, BBC, 28 June 2025.

The following day, six armed groups, namely the Coopérative pour le développement du Congo (CODECO), Zaïre, the Mouvement Populaire d’Autodéfense de l’Ituri (MAPI), the Force de résistance patriotique en Ituri (FRPI), the Front Patriotique et Intégrationniste du Congo (FPIC), and Chini Ya Tuna, signed a cessation of hostilities agreement in Aru, Ituri province.22UN Peacekeeping, ‘PR: MONUSCO welcomes the signing of the cessation of hostilities agreement in Ituri and calls on non-signatory armed groups to join the peace dynamic’, Press release, 1 July 2025; ‘RDC: six groupes armés signent un accord de paix en Ituri’, RFI, 29 June 2025. Nevertheless, violence by and between some of these groups has continued. In early October 2025, MONUSCO publicly condemned killings by CODECO and Zaïre in Ituri, each group claiming to be protecting its own people.23‘RDC: la Monusco condamne l’escalade des violences des groupes armés en Ituri’, RFI, 5 October 2025. The FPAC-Zaire armed group (commonly known as the Ituri Self-Defense Popular Front) is mainly composed of members of the Hema (or Hemu) community.

Serious IHL violations continued beyond the end of June 2025: in July, M23 launched a major offensive operation in Bwisha chefferie in Rutshuru town in North Kivu – a predominantly Hutu area and traditional FDLR stronghold – in which survivors described the summary execution of hundreds of mostly Hutu civilians, including dozens of children (including infants) with machetes and axes.24Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, paras 19, 31.

In mid-November 2025, the DRC government signed a ‘framework for peace’ with M23 in Qatar.25N. Booty, ‘DR Congo and M23 rebels sign framework for peace in Qatar’, BBC, 15 November 2025. The framework, which contained eight protocols on different issues such as humanitarian access, prisoner exchange, the return of IDPs, and the protection of the judiciary, did not, though, end the fighting.26‘M23 says Doha peace talks with DR Congo gov’t expected to continue’, Xinhua, 21 November 2025. In early December, DRC President Felix Tshisekedi and Rwanda President Paul Kagame travelled to Washington, DC, to sign an ‘historic peace and economic agreement’ brokered by US President Donald Trump.27‘Trump to host Rwanda, DRC leaders at White House to sign peace agreement’, Al Jazeera, 1 December 2025.

Peacekeeping

The Southern African Development Community Mission in the DRC (SAMIDRC) was a military force tasked to support the DRC government’s struggle against M23. SAMIDRC deployment began in mid-December 2023 with troops from Malawi, South Africa, and Tanzania.28SADC, ‘Deployment of the SADC Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, News release, 4 January 2024. Its mandate was renewed on 20 November 2024 for a period of one year.29SADC, ‘Communiqué of the Extraordinary Summit of SADC Heads of State and Government 20th November 2024’, Press release, 21 November 2024. But after a surge in attacks in eastern DRC in January 2025, which resulted in the death of fourteen South African soldiers on 13 March 2025 (along with others from Malawi and Tanzania), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) decided to terminate the mission ahead of the stipulated end date.30D. Gatimu, ‘SAMIDRC suffers huge loss against M23’, The Great Lakes Eye, 1 June 2024. Phased withdrawal began in late April 2025,31SADC Secretariat, ‘SADC commences withdrawal of SAMIDRC from the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’, Press release, Gaborone, 1 May 2025, posted on X; ‘SADC troops begin withdrawal from eastern DR Congo’, Xinhua, 2 May 2025. with the final phase initiated in June.32J. Tasamba, ‘SADC announces final phased withdrawal of troops from DR Congo’, AA, 12 June 2025.

MONUSCO has long been supporting the FARDC in the struggle against a range of armed groups in the DRC. Its offensive role in the hostilities alongside the FARDC, conducted through its ‘Force Intervention Brigade’, means that MONUSCO is also a party to the IAC between the DRC and Rwanda (through M23 as its proxy) and the NIAC between the DRC and the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a group affiliated with Islamic State.33‘Uganda: the quiet power in the eastern DRC conflict’, RFI, 23 March 2025. The ADF, which is also known as the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP), is said to have established ties with Islamic State in late 2018. United States (US) Department of State, ‘Country Reports on Terrorism 2019: Democratic Republic of the Congo’. While, at the time of writing, M23 and the ADF had yet to clash with each other, their simultaneous operations in geographically proximate areas was straining the military capacities of the FARDC.34L. Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), 18 June 2025.

As of July 2025, MONUSCO had more than 13,500 personnel in the DRC, of whom almost 10,000 were troops.35UN Peacekeeping, ‘MONUSCO Fact sheet’, 6 October 2025. MONUSCO’s ‘strategic priorities’ are set by the UN Security Council, namely to ‘contribute to the protection of civilians in its area of deployment’ and to ‘support the stabilisation and strengthening of State institutions in the DRC’.36UN Security Council Resolution 2765, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 20 December 2024, operative para 33. After a proposal to withdraw in 2024,37UN Peacekeeping, ‘MONUSCO ending its mission in South Kivu after more than 20 Years of Service’, Press release, Kinshasa, 25 June 2024. MONUSCO’s mandate was extended until 20 December 2025, ‘including, on an exceptional basis and without creating a precedent or any prejudice to the basic principles of peacekeeping, its Force Intervention Brigade’.38UN Security Council Resolution 2765, operative para 31. The mission’s presence beyond that date was uncertain at the time of writing.

The Humanitarian Situation

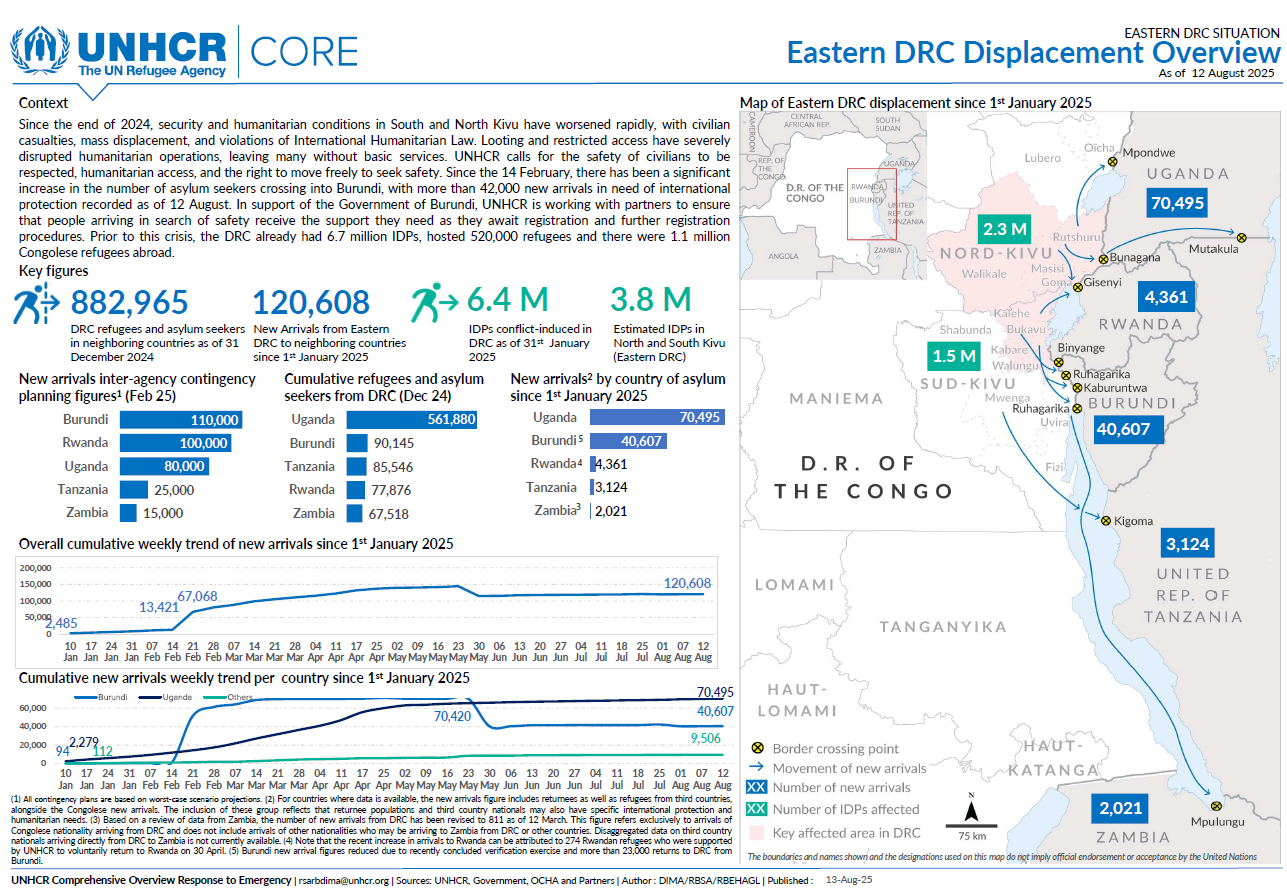

The consequences of the widespread violence in the DRC are also seen in the displacement of civilians, with the DRC home to one of the world’s largest displaced populations.39Ali, ‘Mapping the human toll of the conflict in DR Congo’. More than thirteen million people are facing acute hunger, and over five million have fled their homes.40Oxfam, ‘Crisis in Democratic Republic of Congo’, accessed 1 January 2026. The DRC continues to be one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

International armed conflicts

The conflict between the DRC (and its supporting forces – Burundi, MONUSCO, and SAMIDRC) and M23 is of an international character owing to the level of control exerted by Rwanda over the group. The Group of Experts established pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 2582 found that the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) had ‘effective control’ and exerted ‘de facto direction’ over M23 operations,41Letter dated 3 July 2025 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/446, para 44. meaning that Rwanda is also responsible under international law for the illegal acts of M23.42International Court of Justice (ICJ), Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States), Judgment (Merits), 27 June 1986, para 115; and Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v Serbia and Montenegro), Judgment (Merits), 26 February 2007, para 400. Rwanda is also engaged in belligerent occupation of certain areas within the DRC, both directly and through its proxy, M23. The leader of M23, Sultani Makenga, is a Congolese Tutsi who previously fought in the Rwandan army.

The DRC is a State Party to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Additional Protocol I of 1977.43Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I); adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978. The Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I apply to the IAC with Rwanda and its belligerent occupation of the DRC. Customary IHL also applies to all parties to an IAC.

Members of local ‘Wazalendo’ (meaning ‘patriot’ in Swahili) groups – an ‘eclectic coalition’ of armed groups and self-defence militia armed by Kinshasa to fight M2344Congo Research Group and Ebuteli, ‘Fighting Fire with Fire in Eastern Congo: The Wazalendo Phenomenon and the Outsourcing of Warfare’, Report, May 2025, http://bit.ly/4mTT4BT, p 5. – are to be considered civilians directly participating in hostilities rather than a party to the IAC, as they do not fulfil the criteria for organization, and are neither members of the armed forces nor a militia belonging to them. Indeed, between February and May 2025, there were reports of clashes between Wazalendo fighters and retreating FARDC troops. The clashes facilitated the escape of a reported 770 inmates from Uvira prison on 19 February, including some who had been sentenced for war crimes and crimes against humanity.45Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 17. Individual civilians may be held to have committed war crimes even if they do not belong to a party to an armed conflict.

The UN Secretary-General’s Bulletin of 1999, ‘Observance by United Nations forces of international humanitarian law’, stipulates that the ‘fundamental principles and rules’ of IHL set forth in the Bulletin ‘are applicable to United Nations forces when in situations of armed conflict they are actively engaged therein as combatants, to the extent and for the duration of their engagement’.46‘Secretary-General’s Bulletin. Observance by United Nations forces of international humanitarian law’, UN Doc ST/SGB/1999/13, 6 August 1999, (hereafter, UN Secretary-General’s Bulletin of 1999), §1.1. In addition to the basic IHL rules of targeting, use of anti-personnel mines, booby-traps, and incendiary weapons is explicitly prohibited.47UN Secretary-General’s Bulletin of 1999, §6.2. In certain respects, these prohibitions go beyond the dictates of customary IHL.

Finally, in their July 2025 report, the Group of Experts suggest – but do not definitively conclude – that Uganda, and specifically the Uganda People’s Defence Force (the UPDF), may have gone beyond the terms of consent from Kinshasa to use force on the territory of the DRC. If so, this would amount to an IAC between the DRC and Uganda. Notably, in February and March 2025, without the approval of the Government of the DRC, the UPDF deployed more than 1,000 troops and ‘considerable military materiel to Bunia, as well as Mahagi and Djugu territories’. The operation ‘fell outside the mandate and chain of command of Operation Shujaa’.48Letter dated 3 July 2025 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/446, para 134. This military operation had been launched in 2021 with the consent of the DRC allowing for UPDF deployment to Ituri and North Kivu provinces, ostensibly to clear the area of the ADF. The IHL in Focus Project has not determined that an IAC exists between the DRC and Uganda, but only, as noted below, that the UPDC is engaged in a NIAC with CODECO on the territory of the DRC.

Non-international armed conflicts

There were also five NIACs on the territory of the DRC during the reporting period:

- DRC v Allied Democratic Forces (ADF)

- DRC v Cooperative for Development of the Congo (CODECO)

- UPDF v CODECO

- FDLR v M23

- CODECO v Zaïre.

Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and customary IHL apply to these six NIACs. The DRC is also a State Party to Additional Protocol II of 1977.49Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978. The Protocol, which requires sustained territorial control by an organized armed group, also applies to the NIACs in the east between the FARDC and the ADF and the FARDC and M23.

The FDLR are fighting against M23 in a separate NIAC. In response to the 2025 OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission, the Congolese government stated that formal orders had been issued by the President and FARDC Chief of Staff to prohibit any collaboration with the FDLR.50Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 9, note 8. The FDLR is believed to include in its ranks individuals responsible for the Rwandan genocide; indeed, Kigali describes the group as a ‘genocidal militia’, stating that its existence in eastern DRC threatens its own territory. In February 2025, a Rwandan government spokesperson claimed that the FDLR wanted to return to Rwanda to ‘finish the job’.51Zane and Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What’s the fighting in DR Congo all about?’.

The DRC is a State Party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which it ratified in 2002.52Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002. The current regional focus of the ICC’s investigation is international crimes allegedly perpetrated in North and South Kivu since 1 January 2022.53ICC, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo’, accessed 1 December 2025.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

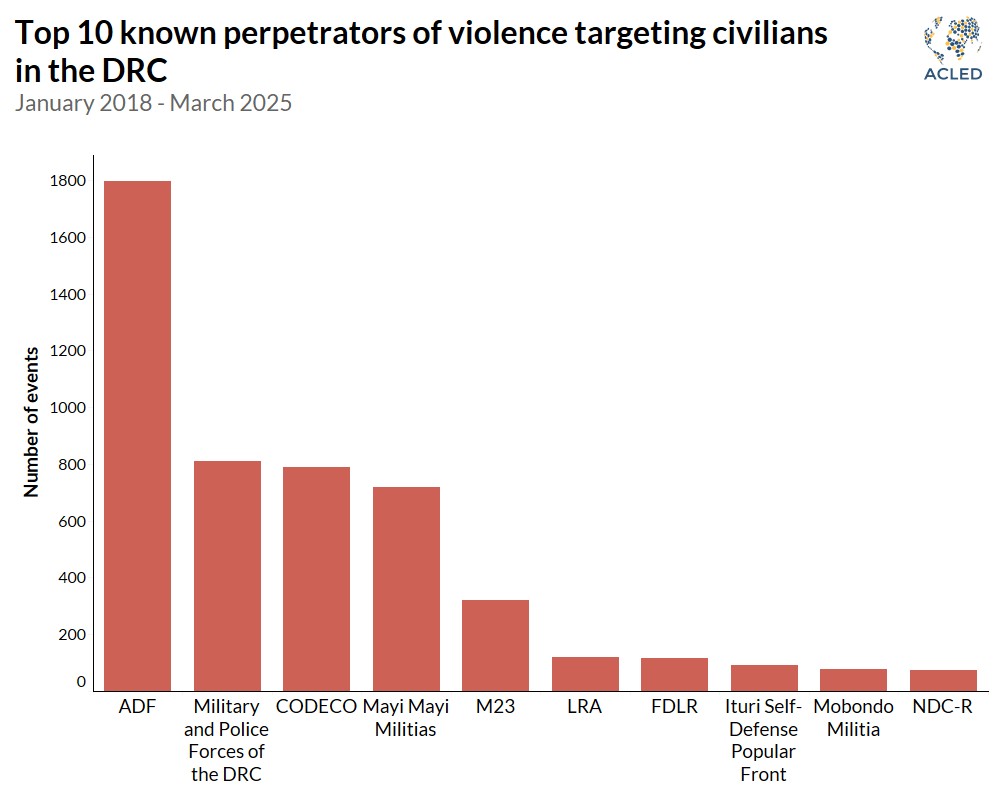

During the reporting period, there were consistent reports of attacks against civilians and civilian objects in the conduct of hostilities, as well as summary executions by many parties, both State and non-State. Violence by all armed groups in the DRC combined caused more than 2,500 reported fatalities (military as well as civilian) in the first three months of 2025, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED).54Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’. The Congolese prime minister, Judith Suminwa, claimed a far higher figure of 7,000 deaths for the first two months of 2025 alone.55O. Le Poidevin, ‘Fighting in Congo has killed 7,000 since January, DRC prime minister says’, Reuters, 24 February 2025.

Writing in July 2025, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect described a combination of indiscriminate use of heavy artillery, shelling, and bombings near civilian areas; alarming levels of conflict-related sexual violence, disproportionately impacting displaced women and girls; and the recruitment of children and their use by a myriad of armed actors as attaining ‘an unprecedented scale’. The security vacuum exacerbated by FARDC’s deployment to fight M23 and MONUSCO’s withdrawal from South Kivu had, the Global Centre said, ‘emboldened other armed groups to remobilize and target civilians’.56Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo, Populations at Risk’, 15 July 2025.

Indeed, as M23 took hold of the east, the ADF capitalized on the chaos, with a ‘surge’ in its targeting of civilians. Rather than replacing local authorities with their own administration as M23 has tended to do, the ADF ‘decimates’ local areas through mass killings, looting, hostage-taking, and the burning of homes.57Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’. On 9 January 2025, M23 and the RDF fought against the FARDC in Kaseghe, a town in Lubero territory in North Kivu. Two days later, the ADF took advantage of the FARDC’s resultant instability to mount an attack in the same locality, reportedly killing eleven civilians. Operation Shujaa is said to have been effective in reducing overall levels of ADF violence, but it has ‘struggled to curb civilian targeting’.58Ibid.

CODECO is a small armed group that has also regularly attacked civilians, particularly ethnic Hemu.CODECO is an ethnic Lendu armed militia known for its attacks on ethnic Hemu.59 E. Duggan, ‘CODECO Militia: Tribal Violence in DRC’, Grey Dynamics, 8 August 2023. CODECO, which has been operating in Ituri province for the last decade, is believed to have been responsible for the deaths of almost 1,800 people in 2018–21. ‘RDC: au moins 55 morts dans une attaque de la CODECO’, Africanews.fr. In February 2025, its militia attacked a set of villages in Djaiba, in Ituri province, where an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp was located. Antoinnette Nzale, the head of the camp, said that at least fifty-five civilians had been killed, although the final toll was expected to have been higher as bodies were still being recovered from burnt-out homes.60‘RDC: au moins 55 morts dans une attaque de la CODECO’, Africanews.fr. MONUSCO issued a statement calling for an accelerated process of disarmament and demobilization, and continues to urge dialogue between ethnic Lendu and Hemu.61J.-T. Okala, ‘Une nouvelle attaque des miliciens de la Codeco repoussée par la MONUSCO et les FARDC en Ituri’, News release, MONUSCO, 17 February 2025.

Civilian Objects under Attack

The ADF and M23 as well as CODECO have regularly attacked civilian objects, especially medical facilities and humanitarian aid warehouses, as well as people’s homes. Under customary IHL, attacks may only be directed against military objectives and must not be directed against civilian objects.62ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Special protection is afforded to medical units, such as hospitals and other medical facilities.63ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28: ‘Medical Units’. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives.64ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.65ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances. Pillage – the looting of private property, including humanitarian and medical supplies – is prohibited under IHL.66Art 4(2)(g), Additional Protocol II; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 52: ‘Pillage’.

Attacks against medical facilities

At least seventy-seven incidents of violence against, or obstruction of, healthcare occurred in eastern DRC in 2024, with most incidents recorded in Ituri and North and South Kivu. Health centres were set on fire, medical supplies were looted, and health workers were killed, kidnapped, or threatened. In Tanganyika province, where reported incidents doubled between 2023 and 2024, vaccination campaigns were repeatedly disrupted by threats and violence.67Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC), ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo: Violence Against Health Care in Conflict 2024’, 18 August 2025.

Looting of vital medical supplies from health facilities was reported on eleven occasions in eastern DRC in 2024, with the ADF, CODECO, and M23 as well as Mai-Mai militia and unidentified armed men cited as the perpetrators. Looters stole laboratory equipment, medicine, mattresses, and nutritional supplies from health centres, hospitals, and pharmacies, predominately across Ituri and North and South Kivu. In one incident, CODECO militia attacked Drodro General Hospital in Ituri province’s Djugu territory, which was supported by Médecins Sans Frontières, pillaging the hospital and pharmacy, killing a patient, and forcing staff and patients to flee.68Ibid, p 5; and see Insecurity Insight, ‘Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition 2024 Report Dataset: 2022-2024 COD SHCC Health Care Data’, Incident No 45446.

Physicians for Human Rights reported that during the takeover of Goma by M23 and their allies, health facilities were subjected to indiscriminate shooting and bombing, with shells falling on the Charité and Virunga hospitals. M23 forces opened fire on an ambulance on mission from Charité hospital and a trainee doctor was shot in the leg. Kyeshero hospital, as with other facilities supported by humanitarian agencies, was looted, as were the warehouses used for storing medical equipment and humanitarian supplies. These violations occurred amid a public health crisis that included outbreaks of mpox and cholera.69K. Naimer, ‘Doctors trapped in hospitals, clinics under fire in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’, Physicians for Human Rights, February 2025.

On 7 February 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that more than seventy (six per cent) of the health facilities in North Kivu had been affected by the increased violence, with some completely destroyed and others struggling to restart operations. Some ambulances had also been damaged. A health clinic in North Kivu supported by WHO was temporarily occupied by armed groups. In some places health workers had to flee, while in others they were working round the clock for days on end, with limited resources and overwhelming demand.70WHO,‘Dire health and humanitarian crisis in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo prompts escalation of efforts by WHO, partners’, News release, 7 February 2025.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) conducted a study in April–May 2025 of 109 health centres in North and South Kivu where the organization operates. The study found that in the areas most exposed to the violence, part of the healthcare system risked total collapse. Three of every five facilities surveyed had been looted since the conflicts escalated.‘Our health centre was looted. They took the equipment and the medicine. Without any medicine, we struggle to treat even everyday illnesses like malaria, respiratory infections and diarrhoea’, said a nurse at a health centre in Kalehe, in South Kivu. Other knock-on effects of these crimes can be similarly devastating.Etienne Penlap, the ICRC’s health coordinator for the DRC, said there had been

a four-fold increase in the number of stillbirths in the facilities included in the study, particularly in North Kivu. This illustrates how hard it is for mothers to access health centres for ante- and postnatal visits. We fear the worst in terms of vaccine coverage for newborns and for mothers and children in a region where there are many epidemics and endemic diseases.71ICRC, ‘DRC: Healthcare system on verge of collapse’, News release, 17 June 2025.

Attacks against humanitarian aid

In the east of the country, multiple warring parties, including M23, the ADF, and, to some extent, Wazalendo militia, have blocked the delivery of aid and provoked further displacement. After M23’s capture of Goma, fighters destroyed aid infrastructure in Goma, causing, among other things, a cholera outbreak. The destruction included more than US$700,000-worth of water and sanitation infrastructure, such as pipelines, latrines, and tanks, forcing people to drink from contaminated streams and lakes.72O. A. Maunganidze and A.-N. Mbiyozo, ‘Displacement as a weapon of war: targeting Africa’s most vulnerable’, Institute for Security Studies, 21 August 2025. The United Nations reported that in Goma criminal activity surged as M23 took control, ‘with home invasions, kidnappings and vehicle hijackings targeting humanitarian agencies. Some incidents have resulted in deaths.’73V. Mishra, ‘Eastern DR Congo: Crisis deepens as crime and insecurity surges’, UN News, 24 February 2025.

More broadly, since March 2025 in North Kivu, a number of NGOs received letters from the de facto General Directorate of Finance requesting tax declarations and threatening enforcement measures. Similar demands emerged in South Kivu in the middle of April. These came on the back of government-related delays on granting access or administrative bottlenecks. A new notification and validation mechanism has also been introduced for the transportation of medical supplies, which require multiple levels of authorization – ‘triple validation’ – which has led to significant delays in the delivery of essential medicines, placing additional threats to safety.74Information provided to the IHL in Focus team by humanitarian actors requesting anonymity.

Civilians under Attack

Under customary IHL, civilians enjoy general protection from the effects of hostilities, unless and for such time as they directly participate in hostilities.75ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Accordingly, parties to armed conflicts must at all times distinguish between combatants and civilians, and are prohibited from directing attacks against civilians.76ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants‘. Civilians may be incidentally affected by attacks against lawful military objectives. However, such attacks must not be disproportionate, and the attacker must take all feasible precautions to avoid, or at the least to minimize, incidental loss of civilian life and injury to civilians (and damage to civilian objects).77ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’; and Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’.

Despite these rules, violence directed against civilians became increasingly widespread in the DRC during the reporting period. While all armed actors have killed and injured civilians, the ADF have been responsible for more cases than any other armed group – and the problem is worsening. The ADF shares photos and videos of its brutality through its own media channels and via Islamic State ‘Central’. In exchange for the affiliation to Islamic State and the depiction in its media of violence typically framed against ‘Christians’, ‘crusaders’, or ‘infidels’, the ADF receives funding and training from the group’s East African hub.78‘Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council’, UN Doc S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, Annex 9.

The ADF camp in Lubero territory is under the leadership of Ahmad Mahmood Hassan, a Tanzanian national commonly known as Abwakasi who has been listed by the UN Security Council’s Sanctions Committee since 20 February 2024.79UN Security Council, ‘Ahmad Mahmood Hassan’, accessed 1 October 2025. This camp was the most deadly toward civilians in the reporting period, with civilian killings by the ADF in Lubero accounting for more than forty per cent of the total caused by the group. Overall civilian fatalities rose by sixty-eight per cent in the first quarter of 2025 compared to the previous quarter – the second-deadliest three months of civilian targeting by the ADF since ACLED began recording data on the group in 1997.80Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’.

Moreover, despite the relative success of Operation Shujaa in eliminating key ADF commanders and dismantling some camps, ADF attacks on civilians have intensified. The ADF has increasingly adopted a ‘survival-oriented approach, relying on opportunistic ambushes or attacks on roads, small villages and farmers for looting, kidnapping, revenge, and fulfilling the jihadist aim of killing “kafir” (non-Muslim infidels).’81Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Annex 6 (paras 19–22). The violence has affected the broader Beni region, north-western Lubero in North Kivu, and southern Ituri, particularly in Mambasa and Irumu territories. June 2024 was the deadliest month on record for ADF-perpetrated civilian killings, with more than 200 deaths reported across Beni, Lubero, and southern Ituri.82Of this number, 190 were documented in Ituri (in the territories of Mambasa and Irumu), and 462 in North Kivu, including Lubero and Beni territories and Butembo. The figure includes only UN-verified incidents, so the true number is likely to be significantly higher. Another international organization operating in the area documented more than 700 killings. Ibid.

OHCHR also received first-hand accounts indicating that at least 319 civilians were killed by M23 fighters, aided by the RDF, between 9 and 21 July in North Kivu. Most of the victims – including at least forty-eight women and nineteen children – were local farmers camping in their fields during the planting season.83‘Armed militia kill hundreds in eastern DR Congo’, UN News, 6 August 2025.

Forced displacement

Of the more than 7 million IDPs in the DRC, 3.8 million are in North and South Kivu provinces. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), around ninety-three per cent of the 5.3 million displacements triggered by conflict and violence in 2024 took place in the east and notably in North Kivu.84IDMC, ‘Country Profile: Congo, Democratic Republic of’, 14 May 2025. Nearly 780,000 people were forced to flee their homes between November 2024 and January 2025 alone. One quarter of the population face food shortages, with movement restrictions in and around Goma significantly hindering the delivery of aid.

By the end of 2024, of the DRC’s total population of some 112 million, armed conflicts, rising food prices, and epidemics had pushed 25 million people into acute food insecurity. Looting of humanitarian warehouses further crippled relief efforts, with large quantities of food, medicine, and medical supplies lost in targeted attacks on humanitarian organizations.85Ali, ‘Mapping the human toll of the conflict in DR Congo’. IHL prohibits the forced displacement of civilians except for their security or for imperative military reasons.86ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 129: ‘The Act of Displacement’. All belligerent actors in eastern DRC have provoked displacement, but the specific action of M23 in unlawfully ordering tens of thousands of the displaced to leave their camps around Goma in February 2025 was a serious violation of IHL and potentially a war crime.Under customary law, ‘ordering the displacement of the civilian population for reasons related to the conflict and not required for the security of the civilians involved or imperative military necessity’ is a war crime.87 ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. On 9 February, M23 told camp leaders and residents of Bulengo and Lushagala IDP camps west of the city they had seventy-two hours to leave. After M23 gave the order, the Lushagala camp was looted and humanitarian organizations were prevented from working there. A camp resident who was at the meeting with M23 told Human Rights Watch:

We tried to explain why we are still here. The majority of us no longer have homes, some have disabilities and need support to travel, others have large families. We don’t have food to sustain ourselves during the trip. But they responded to all of our concerns by saying, ‘What is said is said. By Thursday, everyone should be gone.’88Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: M23 Drives Displaced People From Goma Camps’, 13 February 2025.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

In addition to widespread war crimes, it has been alleged that M23 has committed crimes against humanity. In September 2025, the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission found reasonable grounds to believe that M23 members may have committed, in furtherance of a widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population, the crimes against humanity of murder, torture, rape and sexual slavery, enslavement in ‘training’ camps serving to exact forced labour and military servitude, enforced disappearance, unlawful deprivation of liberty, and deportation or forcible transfer of population.89Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 76.

In parts of Rutshuru where the FDLR is present, M23 has mounted repeated offensives, with reports of mass killings of civilians and restrictions on access to farmland where the Hutu rebels are thought to be active. Prisoners held by M23 in Rutshuru describe appalling conditions of detention.90‘Jean-Jaques’ [a pseudonym], ‘The M23 takeover, part 3: Land grabs and assassinations in DR Congo’s Rutshuru’, The New Humanitarian, 8 October 2025. In July 2025, M23 fighters summarily executed more than one hundred mostly Hutu civilians in at least fourteen villages and farming communities in Rutshuru’s Binza area. Witness accounts and military sources told Human Rights Watch that the Rwandan military participated in the operations.91Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: M23 Mass Killings Near Virunga National Park’, Report, 20 August 2025. In addition to being responsible for its own actions, as mentioned above, since Rwanda exercises effective control over M23 it is also responsible under international law for the actions of M23.

Murder and abduction of civilians

The ADF is also alleged to have committed both war crimes and crimes against humanity. ACLED recorded at least 450 killings by the ADF in the first quarter of 2025, exclusively perpetrated against unarmed civilians. This included the abduction and mass killing of seventy people at a church in Lubero territory on 11 February, which followed simultaneous attacks on five localities in Lubero on 15 January that killed at least 112. Attacks by the group in 2024 had already resulted in the year being the deadliest on record for its targeting of civilians, with more than 1,600 reported deaths.92Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’.

The OHCHR Fact Finding Mission documented deliberate killings of civilians by the FARDC after fighting with Wazalendo, often in retaliation for the victims’ presumed support to the militia. From 15 to 17 February, soldiers from the FARDC’s ‘Guépard’ and ‘Satan II’ units summarily executed at least twenty civilians in Kamanyola, South Kivu. The massacre occurred after hundreds of FARDC troops died during clashes with Wazalendo. Most of the victims – men and teenage boys suspected of belonging to or supporting Wazalendo – were shot in the street or in the course of door-to-door searches. Credible sources believe the death toll to be significantly higher, although the Mission said this required further investigation.93Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 59.

Conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence

The various conflicts have seen an epidemic of sexual and gender-based violence – with the crimes committed by almost every party to the armed conflicts in the country. Victims ranged in age from one year to seventy-five years old.94‘Conflict-related sexual violence – Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, 15 July 2025, para 14. Reports of summary executions of victims after rape persisted. While women and girls continued to constitute the vast majority of victims, men and boys were also affected. Denis Mukwege, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 for his work against sexual violence in the DRC, said: ‘When you have people raping with complete immunity – and think they can go on and on without any consequence – nothing will change.’95‘Sexual violence surged amid war in DRC’s North Kivu last year: UN’, Al Jazeera, 15 August 2025.

The OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission concluded that M23 members perpetrated rape and other forms of sexual violence, including sexual slavery, primarily (but not only) against women and girls. The acts, which involved senior M23 members directly, formed part of a widespread and systematic attack against civilians, occurred ‘daily across the entirety of the territory under M23’s control’. They followed ‘discernible, recurring patterns, indicating a high degree of organization, planning, and resource mobilization’.96Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 77.

The Fact-Finding Missionalso examined whether repeated acts of rape, including gang rape, and other forms of sexual violence committed by specific FARDC units in January and February could similarly amount to crimes against humanity. In particular, the Mission identified a pattern of widespread use of sexual violence by members of FARDC and Wazalendo during their retreat from the frontlines in January and February 2025.97Ibid, para 55. Civil society organizations reported more than 1,000 victims of sexual violence between January and June in South Kivu, mostly women and teenage girls,98The mission cites unnamed civil society sources for this citation. while official sources reported 127 cases of sexual violence in South Kivu in the first two weeks of February alone.99Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 55.

Witnesses and victims described armed men forcing their way into homes, stealing valuables, raping women, girls, and, in some cases, men, and executing those who resisted. One man in South Kivu was stripped naked, severely beaten until he lost consciousness, and gang-raped by FARDC and Wazalendo members. In North Kivu, women and adolescent girls were subjected to gang rapes by retreating FARDC and Wazalendo. One woman was held hostage, tied to a tree and raped daily for two weeks by multiple perpetrators until her family paid a ransom.100Ibid, para 56.

Notwithstanding the consistent pattern across multiple locations and over a wide geographic area, the Mission was unable to conclude whether these acts occurred in course of an attack carried out pursuant to a State policy.101Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 78. Although required under the Rome Statute for material jurisdiction by the International Criminal Court,102Art 7(2)(a), ICC Statute. such a finding is not necessary under customary international criminal law.103See, eg: ICTY, Prosecutor v Kunarac, Kovac and Vukovic, Judgment (Appeals Chamber) (Case Nos IT-96-23 and IT-96-23/1-A), 12 June 2002, para 98. But see also W. A. Schabas, ‘State Policy as an Element of International Crimes’, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol 98, No 3 (Spring 2008).

Individuals who did not belong to M23 have also taken advantage of the chaos as the group seized Goma to commit war crimes, with hundreds of women raped and then burned alive having been attacked in their wing inside the city’s Munzenze prison during a mass jailbreak. The deputy head of MONUSCO, Vivian van de Perre, said that while several thousand men managed to escape from the prison, the area reserved for women was set on fire: ‘There was a major prison breakout of 4,000 escaped prisoners. A few hundred women were also in that prison. They were all raped and then they set fire to the women’s wing. They all died afterwards.’104J. Bastmeijer, S. Houttuin, and M. Townsend, ‘Hundreds of women raped and burned to death after Goma prison set on fire’, The Guardian, 5 February 2025.

The UN Secretary-General, in his report on conflict-related sexual violence for 2024, stated that the hostilities between the FARDC and armed groups ‘propelled mass displacement and exacerbated risks of trafficking for the purposes of sexual slavery and exploitation in and around displacement sites. The intensification of conflict in North Kivu and its spillover in South Kivu, in the context of the withdrawal of MONUSCO from South Kivu in June, resulted in a dramatic surge in sexual violence. More than 17,000 victims were treated between January and May 2024 in North Kivu. Many survivors sought care after violent sexual attacks, including penetration with objects, perpetrated by multiple perpetrators.’105‘Conflict-Related Sexual Violence, Report of the United Nations Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389 15 July 2025, para 30.

The Secretary-General’s report affirmed that armed groups ‘continued to use sexual violence as a tactic to assert control over territory and natural resources’. The number of cases of sexual violence implicating M23 in North Kivu rose from 43 in 2022 to 152 in 2024. While no cases of conflict-related sexual violence have been attributed to the RDF, M23 ‘has continued to receive instructions and support from the Rwanda Defence Force, which exercises de facto control and direction over the group’.106Ibid, para 32. In Ituri, more than fifty cases implicated members of CODECO, who perpetrated gang rape during village incursions. Members of the ADF abducted and sexually enslaved girls during village raids and forced them to marry fighters. 107Ibid.

Attacks against journalists

DRC is an extremely dangerous place to be a journalist – and not only close to the front lines. As Reporters Without Borders has stated: ‘Arrests, assaults, threats, forced disappearances, executions, media outlets suspended, looted, ransacked, and more — journalists in the DRC operate in a climate of great insecurity.’ The group says the security forces are implicated in numerous violations, ‘and enjoy total impunity’.

Due to the conflicts in the east, many journalists are forced to flee their place of work and are subjected to attacks and persecution. Between January 2024 and January 2025 in North Kivu, more than twenty-five community radio stations were looted or forced to shut down, and over fifty attacks on newsrooms and journalists were documented.108Reporters Without Borders, ‘Democratic Republic of Congo’, accessed 29 September 2025. ‘As soon as the rebels entered, we changed our programming schedules’, a journalist told The New Humanitarian. ‘News programmes, talk shows, and programmes dealing with security are no longer broadcast.’ A local radio journalist from another village said his station suspended broadcasts after rebels looted their small studio – taking not just the mixer, computers, and microphones, but even plastic chairs and the mattress they slept on for night shifts. ‘We don’t want any martyrs’, said the reporter. ‘We’ve noticed that we journalists are the most targeted [by M23].’109‘Mira’ [a pseudonym], ‘The M23 takeover, part 2: Congolese describe domination and defiance in south Lubero’, The New Humanitarian, 6 October 2025.

Government ministers have regularly accused journalists of supporting terrorism for reporting on rebel advances, suspended Al Jazeera and withdrawn accreditation for the broadcaster’s reporters, and threatened to suspend other media outlets.110Committee to Protect Journalists, ‘Journalists covering eastern DRC conflict face death threats, censorship’, Kinshasa, 30 January 2025. Discouraging the armed forces via the media in wartime is a criminal offence punishable by death.Circular Note No 202 issued by the Minister of Justice, Rose Mutombo, and signed on 13 March 2024. According to the document, the penalty will be applied to those guilty of acts of ‘treason and espionage’. 111G. Murhabazi, ‘Réactions en cascade après le rétablissement de la peine de mort en RDC: le pays revient “aux années sombres du Mobutisme”’, RTBF Actus, 16 March 2024. This penalty is itself a violation of international law, which only allows the imposition of capital punishment for the ‘most serious crimes’,112Art 6(2), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; adopted at New York, 16 December 1966; entered into force, 23 March 1976. defined as limited to those involving intentional killing.113Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 36 – Article 6: right to life, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/36, 3 September 2019, para 35.

In a 7 January 2025 post on social media site X, Christian Bosembe, the president of the Higher Council for Audiovisual and Communication (CSAC), threatened to suspend French news outlets Radio France Internationale (RFI), France 24, and TV5 Monde’s Africa programme for reporting the ‘alleged advances of terrorists’.114Committee to Protect Journalists, ‘Journalists covering eastern DRC conflict face death threats, censorship’. ‘We respect freedom of expression and information’, he claimed, ‘but we firmly condemn any apology for terrorism. Terrorists have no right to speak in our country’. When government forces recaptured territory a few days later, the Minister of Justice, Constant Mutamba, congratulated them on X, while warning that anyone who ‘reports the activities’ of M23 and Rwandan forces ‘will now suffer the full force of the law (DEATH PENALTY.)’115Post on X, 9 January 2025. In the original French, ‘Tout acteur politique, de la société civile, journaliste, religieux, qui relayera les activités de l’armée rwandaise et ses supplétifs du M23, subira désormais la rigueur de la loi (PEINE DE MORT). Notre intégrité territoriale ne se marchande pas.’ [Capitals in original]. The DRC ended a twenty-one-year moratorium on executions in 2024.116N. Kruijning, ‘DR Congo reinstates death penalty after 21 years amid escalating violence and militant attacks’, Erasmus School of Law, The Netherlands, 17 March 2024.

- 1Center for Preventive Action, ‘Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, Council for Foreign Relations, Updated 16 December 2025.

- 2Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, Geneva, 5 September 2025, para 8. See also: Letter dated 10 June 2022 from the Group of Experts extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2582 (2021) addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2022/479, 14 June 2022, Annex 39.

- 3See eg: Letter dated 3 July 2025 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/446, 3 July 2025, paras 44, 45. Shortly after its creation in 2012, M23 rapidly gained territory and seized Goma – acts that saw accusations of war crimes and human rights abuses. After being forced to withdraw from Goma, the group suffered a series of heavy defeats at the hands of the DRC army along with a UN force that saw it expelled from the country. M23 fighters agreed to be integrated into the army in return for promises that Tutsis would be protected. But in 2021, the group took up arms again, saying the promises had been broken. The group take its name from a peace agreement that was signed with a previous Tutsi-led rebel group on 23 March 2009. D. Zane and W. Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What is the fighting about and is Rwanda involved?’, BBC, 27 January 2025 (Updated 1 July 2025).

- 4International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), Prosecutor v Tadić(aka ‘Dule’), Judgment (Appeals Chamber) (Case No IT-94-1-A), 15 July 1999, para 131; International Criminal Court, Prosecutor v Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, Judgment (Trial Chamber I) (Case No ICC-01/04-01/06), 14 March 2012, para 541; Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 20.

- 5K. Diya (a pseudonym), ‘The M23 takeover, part 1: In DR Congo’s Walikale, forced labour and fears of arrest’, The New Humanitarian, 1 October 2025.

- 6E. Makumeno, ‘Second DR Congo city falls to Rwanda-backed rebels’, BBC, 16 February 2025.

- 7

- 8‘RDC: au moins 55 morts dans une attaque de la CODECO’, Africanews.fr, 11 February 2025.

- 9Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 12.

- 10Ibid, paras 26, 30–34, 42–43, 49–50, 55–56, 59.

- 11M. Ali, ‘Mapping the human toll of the conflict in DR Congo’, Explainer, Al Jazeera, 24 March 2025; ‘DRC M23 rebels to withdraw from Walikale in peace gesture’, Al Jazeera, 22 March 2025.

- 12‘Congo rebels leave strategic town ahead of planned Doha talks’, Reuters, 4 April 2025.

- 13

- 14Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 93.

- 15P. Asanzi, ‘The revived Luanda Process – inching towards peace in east DRC?’, Institute for Security Studies, 21 October 2024

- 16East African Court of Justice, ‘Court Hears Applications Arising From Case Filed by DRC Against Rwanda Over Alleged Conflicts in North Kivu Region’, Arusha, 27 September 2024.

- 17ICC, ‘Statement of ICC Prosecutor Karim A. A. Khan KC on the Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and renewed investigations’, Press release, 14 October 2024.

- 18‘Burundi warns Rwanda as eastern DR Congo conflict advances’, RFI, 12 February 2025.

- 19Zane and Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What is the fighting about and is Rwanda involved?’.

- 20S. Lawal, ‘Kabila sentenced to death: What it means for DRC and what’s next’, Explainer, Al Jazeera, 2 October 2025.

- 21P. Nije, ‘DR Congo-Rwanda peace deal met with scepticism in rebel-held city’, BBC, 28 June 2025.

- 22UN Peacekeeping, ‘PR: MONUSCO welcomes the signing of the cessation of hostilities agreement in Ituri and calls on non-signatory armed groups to join the peace dynamic’, Press release, 1 July 2025; ‘RDC: six groupes armés signent un accord de paix en Ituri’, RFI, 29 June 2025.

- 23‘RDC: la Monusco condamne l’escalade des violences des groupes armés en Ituri’, RFI, 5 October 2025.

- 24Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, paras 19, 31.

- 25N. Booty, ‘DR Congo and M23 rebels sign framework for peace in Qatar’, BBC, 15 November 2025.

- 26‘M23 says Doha peace talks with DR Congo gov’t expected to continue’, Xinhua, 21 November 2025.

- 27‘Trump to host Rwanda, DRC leaders at White House to sign peace agreement’, Al Jazeera, 1 December 2025.

- 28SADC, ‘Deployment of the SADC Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, News release, 4 January 2024.

- 29SADC, ‘Communiqué of the Extraordinary Summit of SADC Heads of State and Government 20th November 2024’, Press release, 21 November 2024.

- 30D. Gatimu, ‘SAMIDRC suffers huge loss against M23’, The Great Lakes Eye, 1 June 2024.

- 31SADC Secretariat, ‘SADC commences withdrawal of SAMIDRC from the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’, Press release, Gaborone, 1 May 2025, posted on X; ‘SADC troops begin withdrawal from eastern DR Congo’, Xinhua, 2 May 2025.

- 32J. Tasamba, ‘SADC announces final phased withdrawal of troops from DR Congo’, AA, 12 June 2025.

- 33‘Uganda: the quiet power in the eastern DRC conflict’, RFI, 23 March 2025. The ADF, which is also known as the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP), is said to have established ties with Islamic State in late 2018. United States (US) Department of State, ‘Country Reports on Terrorism 2019: Democratic Republic of the Congo’.

- 34L. Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), 18 June 2025.

- 35UN Peacekeeping, ‘MONUSCO Fact sheet’, 6 October 2025.

- 36UN Security Council Resolution 2765, adopted by unanimous vote in favour on 20 December 2024, operative para 33.

- 37UN Peacekeeping, ‘MONUSCO ending its mission in South Kivu after more than 20 Years of Service’, Press release, Kinshasa, 25 June 2024.

- 38UN Security Council Resolution 2765, operative para 31.

- 39Ali, ‘Mapping the human toll of the conflict in DR Congo’.

- 40Oxfam, ‘Crisis in Democratic Republic of Congo’, accessed 1 January 2026.

- 41Letter dated 3 July 2025 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/446, para 44.

- 42International Court of Justice (ICJ), Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States), Judgment (Merits), 27 June 1986, para 115; and Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v Serbia and Montenegro), Judgment (Merits), 26 February 2007, para 400.

- 43Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I); adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978.

- 44Congo Research Group and Ebuteli, ‘Fighting Fire with Fire in Eastern Congo: The Wazalendo Phenomenon and the Outsourcing of Warfare’, Report, May 2025, http://bit.ly/4mTT4BT, p 5.

- 45Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 17.

- 46‘Secretary-General’s Bulletin. Observance by United Nations forces of international humanitarian law’, UN Doc ST/SGB/1999/13, 6 August 1999, (hereafter, UN Secretary-General’s Bulletin of 1999), §1.1.

- 47UN Secretary-General’s Bulletin of 1999, §6.2.

- 48Letter dated 3 July 2025 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/446, para 134.

- 49Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978.

- 50Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 9, note 8.

- 51Zane and Chibelushi, ‘DR Congo’s M23 conflict: What’s the fighting in DR Congo all about?’.

- 52Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002.

- 53ICC, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo’, accessed 1 December 2025.

- 54Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’.

- 55O. Le Poidevin, ‘Fighting in Congo has killed 7,000 since January, DRC prime minister says’, Reuters, 24 February 2025.

- 56Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo, Populations at Risk’, 15 July 2025.

- 57Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’.

- 58Ibid.

- 59E. Duggan, ‘CODECO Militia: Tribal Violence in DRC’, Grey Dynamics, 8 August 2023. CODECO, which has been operating in Ituri province for the last decade, is believed to have been responsible for the deaths of almost 1,800 people in 2018–21. ‘RDC: au moins 55 morts dans une attaque de la CODECO’, Africanews.fr.

- 60‘RDC: au moins 55 morts dans une attaque de la CODECO’, Africanews.fr.

- 61J.-T. Okala, ‘Une nouvelle attaque des miliciens de la Codeco repoussée par la MONUSCO et les FARDC en Ituri’, News release, MONUSCO, 17 February 2025.

- 62ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 63

- 64

- 65ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

- 66

- 67Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC), ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo: Violence Against Health Care in Conflict 2024’, 18 August 2025.

- 68Ibid, p 5; and see Insecurity Insight, ‘Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition 2024 Report Dataset: 2022-2024 COD SHCC Health Care Data’, Incident No 45446.

- 69K. Naimer, ‘Doctors trapped in hospitals, clinics under fire in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’, Physicians for Human Rights, February 2025.

- 70WHO,‘Dire health and humanitarian crisis in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo prompts escalation of efforts by WHO, partners’, News release, 7 February 2025.

- 71ICRC, ‘DRC: Healthcare system on verge of collapse’, News release, 17 June 2025.

- 72O. A. Maunganidze and A.-N. Mbiyozo, ‘Displacement as a weapon of war: targeting Africa’s most vulnerable’, Institute for Security Studies, 21 August 2025.

- 73V. Mishra, ‘Eastern DR Congo: Crisis deepens as crime and insecurity surges’, UN News, 24 February 2025.

- 74Information provided to the IHL in Focus team by humanitarian actors requesting anonymity.

- 75

- 76

- 77ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’; and Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’.

- 78‘Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council’, UN Doc S/2024/969, 27 December 2024, Annex 9.

- 79UN Security Council, ‘Ahmad Mahmood Hassan’, accessed 1 October 2025.

- 80Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’.

- 81Letter dated 27 December 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Annex 6 (paras 19–22).

- 82Of this number, 190 were documented in Ituri (in the territories of Mambasa and Irumu), and 462 in North Kivu, including Lubero and Beni territories and Butembo. The figure includes only UN-verified incidents, so the true number is likely to be significantly higher. Another international organization operating in the area documented more than 700 killings. Ibid.

- 83‘Armed militia kill hundreds in eastern DR Congo’, UN News, 6 August 2025.

- 84IDMC, ‘Country Profile: Congo, Democratic Republic of’, 14 May 2025.

- 85Ali, ‘Mapping the human toll of the conflict in DR Congo’.

- 86

- 87

- 88Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: M23 Drives Displaced People From Goma Camps’, 13 February 2025.

- 89Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 76.

- 90‘Jean-Jaques’ [a pseudonym], ‘The M23 takeover, part 3: Land grabs and assassinations in DR Congo’s Rutshuru’, The New Humanitarian, 8 October 2025.

- 91Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: M23 Mass Killings Near Virunga National Park’, Report, 20 August 2025.

- 92Serwat, ‘As M23 rebels take hold of eastern Congo, the Islamic State is capitalizing on the chaos’.

- 93Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 59.

- 94‘Conflict-related sexual violence – Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, 15 July 2025, para 14.

- 95‘Sexual violence surged amid war in DRC’s North Kivu last year: UN’, Al Jazeera, 15 August 2025.

- 96Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 77.

- 97Ibid, para 55.

- 98The mission cites unnamed civil society sources for this citation.

- 99Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 55.

- 100Ibid, para 56.

- 101Report of the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission on the situation in North and South Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, UN Doc A/HRC/60/80, para 78.

- 102Art 7(2)(a), ICC Statute.

- 103See, eg: ICTY, Prosecutor v Kunarac, Kovac and Vukovic, Judgment (Appeals Chamber) (Case Nos IT-96-23 and IT-96-23/1-A), 12 June 2002, para 98. But see also W. A. Schabas, ‘State Policy as an Element of International Crimes’, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol 98, No 3 (Spring 2008).

- 104J. Bastmeijer, S. Houttuin, and M. Townsend, ‘Hundreds of women raped and burned to death after Goma prison set on fire’, The Guardian, 5 February 2025.

- 105‘Conflict-Related Sexual Violence, Report of the United Nations Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389 15 July 2025, para 30.

- 106Ibid, para 32.

- 107Ibid.

- 108Reporters Without Borders, ‘Democratic Republic of Congo’, accessed 29 September 2025.

- 109‘Mira’ [a pseudonym], ‘The M23 takeover, part 2: Congolese describe domination and defiance in south Lubero’, The New Humanitarian, 6 October 2025.

- 110Committee to Protect Journalists, ‘Journalists covering eastern DRC conflict face death threats, censorship’, Kinshasa, 30 January 2025.

- 111G. Murhabazi, ‘Réactions en cascade après le rétablissement de la peine de mort en RDC: le pays revient “aux années sombres du Mobutisme”’, RTBF Actus, 16 March 2024.

- 112Art 6(2), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; adopted at New York, 16 December 1966; entered into force, 23 March 1976.

- 113Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 36 – Article 6: right to life, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/36, 3 September 2019, para 35.

- 114Committee to Protect Journalists, ‘Journalists covering eastern DRC conflict face death threats, censorship’.

- 115Post on X, 9 January 2025. In the original French, ‘Tout acteur politique, de la société civile, journaliste, religieux, qui relayera les activités de l’armée rwandaise et ses supplétifs du M23, subira désormais la rigueur de la loi (PEINE DE MORT). Notre intégrité territoriale ne se marchande pas.’ [Capitals in original].

- 116N. Kruijning, ‘DR Congo reinstates death penalty after 21 years amid escalating violence and militant attacks’, Erasmus School of Law, The Netherlands, 17 March 2024.