Conflict Overview

The extent of violence in the multiple armed conflicts in Iraq remained relatively low during the reporting period. The non-international armed conflict (NIAC) between Iraq, supported by the Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF-OIR), and Islamic State (also called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, ISIL) continued to lessen in intensity, largely as a result of sustained counterterrorism operations by Iraqi forces and the CJTF-OIR.1A. Mehvar et al, ‘Middle East Overview: January 2025’, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), 4 July 2025. Nevertheless, concerns persist about a potential resurgence of the group. Islamic State mounted periodic attacks, mostly in remote and rural areas, and primarily using small arms and light weapons.

Following the renewed hostilities between Israel and Hamas on 7 October 2023, a growing number of violent confrontations between the United States and a decentralized network of Shia militias operating under the banner of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI) were reported. Combat between October 2023 and February 2024 was of such intensity, and the IRI was sufficiently organized, such that a NIAC existed under international humanitarian law (IHL). That said, the violence subsequently subsided, indicating that the conflict had ended before the current reporting period. At the same time, the United States has conducted regular airstrikes targeting factions of the IRI seemingly without the consent of the Iraqi government, indicating the existence of an international armed conflict (IAC).

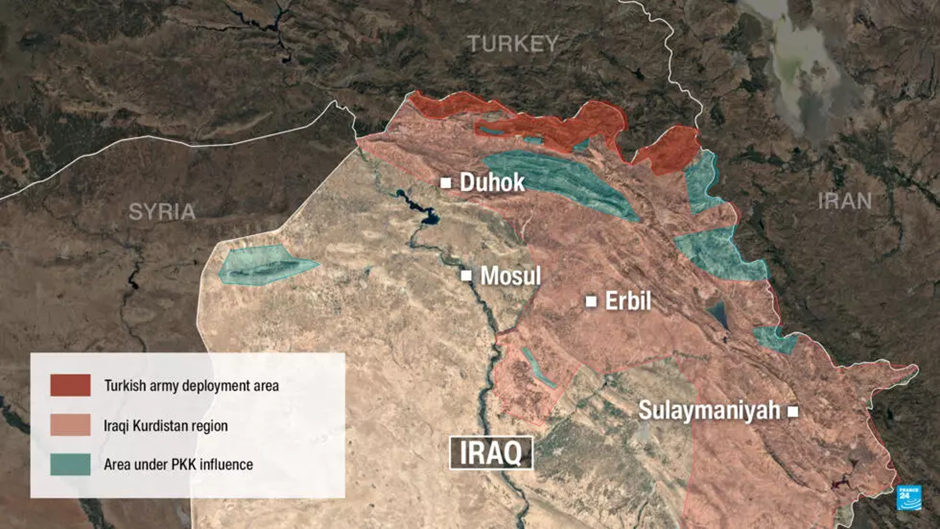

In the broader context of the cross-border conflict between Türkiye and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Türkiye has conducted frequent airstrikes and ground operations targeting PKK positions in northern Iraq, notably in the Sinjar region, impacting on the Yazidi community who had been displaced by Islamic State in 2014. These operations continued despite the PKK’s announcement on 12 May 2025 that it was ending its armed struggle against Türkiye.2N. Ezzeddine, ‘Q&A – Disbanding the PKK: A Turning Point in Turkey’s Longest War?’, ACLED, 25 July 2025. Despite growing diplomatic ties between Iraq and Türkiye, including through the signing of agreements to cooperate on defence and security matters, the military operations against the PKK on Iraqi territory occur without Iraq’s consent and therefore amount also to an IAC between the two States.3‘Turkey and Iraq Deepen Ties with Landmark Agreements and Regional Dialogue’, Syriac Press, 9 May 2025.

In part owing to the ongoing violence, the humanitarian situation remains fragile. As of December 2024, more than one million people were internally displaced within Iraq. Most are in private accommodation in urban areas or informal settings, but an estimated 107,000 individuals were in 20 camps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) in the north.4Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR), ‘UNHCR IRAQ Update March 2025’, 24 April 2025. Many have been displaced for more than seven years and continue to live in very poor conditions; these continue to worsen due to funding shortfalls.5Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘NRC’s Operations in Iraq’, Fact Sheet, May 2025, p 1.

The United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (UNITAD) ended its work on 17 September 2024.6UNITAD, ‘Statement from the Acting Special Adviser and Head of UNITAD on the Conclusion of the UNITAD Mandate’, Baghdad, 16 September 2024. UNITAD’s closure raises concerns about accountability for past violations, the management and preservation of evidence (in particular in light of the existence of multiple mass graves), and the future of proposed incorporation of international crimes into Iraqi domestic criminal law.7Since UNITAD’s closure, European prosecutors bringing cases against Islamic State-affiliated individuals are said to have experienced significant difficulties in accessing material in its database, which is held by the UN Office of Legal Affairs in New York. Information provided in email from Sareta Ashraph, 13 October 2025.

On this issue, Iraq has still to enact penal legislation to punish war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, despite regular pledges to do so. Conflict-related incidents continue to be prosecuted under the anti-terrorism law,8Anti-Terrorism Law (No 13) of 2005), unofficial English translation at: http://bit.ly/4nbcfrG. which has been criticized for its broad and ambiguous wording. Moreover, the law does not recognize conflict-related sexual violence as a form of terrorism, leaving a major gap in the capacity to prosecute Islamic State affiliates for such acts.9E. U. Ochab, ‘Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Personal Status and General Amnesty Laws’, Forbes, 26 January 2025.

In January 2025, the Iraqi parliament passed a law providing for an amnesty for certain prisoners convicted under the terrorism law. This is said to have had a detrimental impact on parts of the Iraqi population, particularly women and girls, as well as the minority communities who were targeted by Islamic State.10Ibid.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

During the reporting period, there were two international armed conflicts (IACs) involving Iraq:

- An IAC between Iraq and Türkiye.

- An IAC between Iraq and the United States.

These IACs both occur because the two foreign States in question are using force on the territory of Iraq without Iraq’s consent.

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and customary IHL apply to these two IACs. Additional Protocol I of 1977 does not apply as neither Türkiye nor the United States is a State Party.

There were also two non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) in Iraq:

- Iraq (supported by the CJTF-OIR) v Islamic State.

- Türkiye v PKK.

These two conflicts are governed by Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions and customary IHL. Iraq is not a party to Additional Protocol II of 1977, meaning this treaty does not apply to the hostilities with Islamic State. In any event, although the requirement for territorial control could be met in the case of Türkiye’s conflict with the PKK, for the Protocol to apply, one of the parties must be the armed forces of the territorial State.11The material jurisdiction of the Protocol is limited to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups.…’ [added emphasis]. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II of 1977.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

Hundreds of civilian casualties occurred during the reporting period. Civilian objects were regularly attacked, in particular by parties to the armed conflicts that took place in areas under the control of the Turkish Armed Forces. The targets of Turkish attacks included objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population and cultural property. There were also claims of indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks by Islamic State, Iraqi armed forces, and Türkiye. There is no available evidence to indicate that any of the US attacks violated IHL.

There were reports of forcible displacement of civilians by the Turkish Armed Forces without lawful justification. A range of protection concerns persist for those in the power of the various parties to armed conflict. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Iraq and Syria, including those displaced in earlier conflicts, continue to face serious obstacles to return and reintegration, owing to a lack of official documentation, socio-economic exclusion, and lack of housing. Landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) continue to endanger civilian lives, obstruct safe movement and access to services, and impede agriculture and livestock farming.

There were continued reports of arbitrary detention of individuals by Iraqi authorities in connection with the conflict with Islamic State. Evidence also suggests violations of fundamental fair-trial guarantees, arbitrary application of death sentences, and unlawful mass executions. Finally, the existence of multiple mass graves across the territory invokes the Iraqi government’s obligation under international law to investigate possible war crimes occurring on its territory.12International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’.

Civilian Objects under Attack

Under customary IHL, attacks may only be directed against military objectives. Attacks must not be directed against civilian objects.13ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives14ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. and, as such, are protected against attack.15ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 10: ‘Civilian Objects’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.16ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.[4] Additionally, certain civilian objects are afforded special protection due to their importance to the survival of the civilian population.17ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 54: ‘Attacks against Objects Indispensable to the Survival of the Civilian Population’. Indiscriminate attacks are unlawful.18ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’.

Attacks against objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population

Türkiye’s continued air and ground campaign against the PKK in northern Iraq has resulted in significant destruction of agricultural and grazing areas – often the primary source of income for many civilians in the area.19‘Persistent Turkish Military Strikes Target Civilian Residences in Iraqi Kurdistan’, Medya News, 25 September 2024. As of September 2024, attacks were reported to have destroyed at least 6,500 hectares of farmland and forest in northern Iraq.20T. Krüger, ‘As Turkey Escalates Attacks in Iraq, Kurdish Journalists Are Becoming Targets’, Truthout, 9 September 2024.

In June 2025, in Duhok province, heavy bombardments by Turkish Armed Forces sparked destruction of thousands of dunams of land21One dunam equals approximately 900 square metres. used to cultivate grapes, walnuts, almonds, and sumac.22‘Turkish artillery causes large wildfire in Iraq’s Duhok’, Shafaq News, 20 June 2025. As one local resident, Ahmad Saadullah, who lives in the village of Guharze, recalled: ‘We used to live off our farming, livestock, and agriculture.’ But in recent years, the local population has been dependent on government aid and ‘unstable, seasonal jobs’. These days, he said, ‘we live with warplanes, drones, and bombings’.23S. Martany, ‘Iraq’s Displaced Kurds Hope to Return Home after Turkey’s Kurdish Militants Declare a Ceasefire’, Associated Press News, 2 March 2025. The widespread destruction of agricultural land prompted many civilians to leave their homes.24K. Faidhi Dti, ‘“We Were Surrounded by Fire”: Duhok Villagers Battle Blazes Blamed on Turkish Bombs’, RUDAW, 8 August 2024. Adil Tahir Qadir, for instance, could not return to his village of Barchi. ‘Because of Turkish bombing’, he said, ‘all of our farmlands and trees were burned’.25Martany, ‘Iraq’s Displaced Kurds Hope to Return Home after Turkey’s Kurdish Militants Declare a Ceasefire’.

Targeting of civilian objects

Evidence points to the deliberate targeting of civilian property by Turkish Armed Forces in the KRI during the reporting period. On 17 April 2025, for example, a residential home in the village of Spindare was bombed, reportedly by the Turkish Air Force.26‘Turkey Attempts to Neutralise PKK Tunnels in Iraq despite Dissolution of Kurdish Militant Group’ France 24, 10 July 2025. Turkish authorities have alleged that the village was being used as a logistical or supply point by PKK fighters. No evidence, however, has been proffered that the PKK was using the house. In the absence of verified evidence that targeted homes were military objectives, the strikes breach the fundamental IHL principle of distinction.

Other attacks may also have been unlawful. Between 10 and 16 September 2024, Makhmour refugee camp was struck twice by Turkish drones, reportedly while UN and Iraqi authorities were visiting the area. Türkiye sought to justify the strikes by alleging the presence of PKK operatives and training sites within the camp. However, no public evidence substantiates the claim that the camps constituted military objectives under IHL.27‘TI113 – September 10, 2024’, Airwars, 10 September 2024. This pattern continued with another strike on 1 July 2025 against an IDP camp in Duhok governorate, which houses large numbers of Yazidi civilians. The United Nations in Iraq publicly condemned the attack and urged the Iraqi government to investigate and take preventive measures to prevent a recurrence.28UN, ‘United Nations in Iraq Condemns Attack in IDP Camp in Duhok’, Press release, 1 July 2025.

Between 15 and 18 April 2025, Turkish Armed Forces are reported to have launched more than 600 strikes using fighter jets, drones, and artillery.29‘Turkey Expands Military Operations in Iraq as Cross-Border Attacks Intensify’, Medya News, 20 April 2025. The cumulative impact of these operations has been to inflict extensive damage to civilian property that has rendered large areas uninhabitable. The scale and intensity of the violence, combined with the apparent targeting of areas known to be populated or previously inhabited by civilians, suggest either indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks.30ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’. Even in circumstances where military objectives may be present in the locations being attacked, the failure to take all feasible precautions to verify targets, minimize civilian harm, and avoid damage to civilian property would breach IHL.

Destruction of cultural property

The reporting period also saw persistent allegations of destruction of objects of significant cultural and spiritual importance to minority groups in Iraq, particularly Kurdish communities. On 22 February 2025, for example, the Turkish Armed Forces bombed the Shekhy cave in Amedi, a historically significant site associated with an important Kurdish revolutionary figure.31Community Peacemaker Teams, ‘The Continuation of Turkish Military Operations in Iraqi Kurdistan Despite PKK’s Unilateral Ceasefire’, 2 April 2025. Incidents such as these seem to be part of Türkiye’s wider military effort to neutralize the PKK’s operations from the network of tunnels the group has built in the region.32‘Turkey Attempts to Neutralise PKK Tunnels in Iraq despite Dissolution of Kurdish Militant Group’. However, there is no evidence to suggest that cultural sites effectively contributed to PKK’s military activities – that the PKK used those sites for military activities against Türkiye or that it was about to do so.33Community Peacemaker Teams, ‘The Continuation of Turkish Military Operations in Iraqi Kurdistan Despite PKK’s Unilateral Ceasefire’. In the absence of such evidence, the destruction of such sites violates the principle of distinction as well as the special protection to be accorded to cultural property under IHL.34ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 38: ‘Attacks Against Cultural Property’.

Civilians under Attack

Under customary IHL, civilians enjoy protection against attack, unless and for such time as they directly participate in hostilities.35ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants’; and Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. Accordingly, parties to armed conflicts must at all times distinguish between combatants and civilians, and are prohibited from directing attacks against civilians. In case of doubt, persons must be treated as civilians.36ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. The accompanying commentary states that in NIACs, ‘the issue of doubt has hardly been addressed in State practice, even though a clear rule on this subject would be desirable as it would enhance the protection of the civilian population against attack.’ One ‘cannot automatically attack anyone who might appear dubious….’ The same approach with respect to IACs ‘seems justified’ in NIACs. Civilians may be incidentally affected by attacks against lawful targets. However, such attacks must be proportionate, and the attacker must take all feasible precautionary measures to avoid, and in any event to minimize, incidental effects on civilians.

Attacks against journalists

Under IHL, journalists are protected against attack, unless and for such times as they directly participate in hostilities.37ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 34: ‘Journalists’. Yet, the reporting period revealed several instances of journalists being attacked by the Turkish Armed Forces, seemingly on the basis that they were considered members of the PKK. On 8 July 2024, for instance, a Turkish drone struck a vehicle belonging to a Yazidi-focused media outlet, injuring six people. While some sources indicate the passengers were civilians, Türkiye asserted they were affiliated with the PKK.38‘TI108 – July 8, 2024’, Airwars, 8 July 2024. Similarly, on 11 August 2024, a drone strike hit a vehicle carrying staff from a media outlet reportedly funded by the PKK, killing two people and injuring six others. Most independent reports described the victims as civilians. However, regional authorities later claimed one person to have been a PKK official.39‘TI111 – August 23, 2024’, Airwars, 23 August 2024.

These assaults occur within a context in which journalists reporting on Turkish operations in northern Iraq express growing concern about being targeted. Claims of increased intimidation and violence against media professionals are widely circulating.40Reporters Without Borders, ‘RSF alarmed by surge in violence against journalists in Iraqi Kurdistan’, RSF, 21 August 2024. In July 2024, a court in Iraqi Kurdistan’s Duhok province sentenced Suleiman Ahmed, the editor-in-chief of Rojnews’ Arabic section, to three years for espionage and alleged membership of a Kurdish party close to the PKK.41Ibid. In light of these events, Jonathan Dagher, head of Reporters Without Borders’ Middle East desk, warned that Iraqi Kurdistan ‘is becoming one of the most dangerous places in the world for reporters.’42T. Krüger, ‘As Turkey Escalates Attacks in Iraq, Kurdish Journalists Are Becoming Targets’.

Absent clear evidence that the individuals were directly participating in hostilities at the time, these attacks raise serious concerns about Turkish compliance with the principle of distinction and the duty to take feasible precautions in attack. Moreover, the recurrent attacks against journalists may also constitute a violation of the obligation to respect and protect them in the exercise of their activities.43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 34: ‘Journalists’.

Forced displacement

During the reporting period, serious concerns emerged about conflict-related displacement of Kurdish minority communities as a result of Turkish military operations in Iraq. Under customary IHL, parties to a NIAC are prohibited from ordering the displacement of the civilian population in relation to the conflict unless required for their security or for imperative military reasons.44ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 129: ‘The Act of Displacement’. Breaches of these prohibitions constitute serious violations of IHL and may amount to war crimes.45ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. Such displacement must be temporary, with all possible measures taken to ensure proper shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition and that members of the same family are not separated.46ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 131: ‘Treatment of Displaced Persons’. The prohibition aims to protect civilian populations from arbitrary or punitive displacement and to uphold their rights to remain in or return to their homes.47ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’.

Military operations by the Turkish Armed Forces in the affected regions appear to have again displaced many hundreds of civilians, in particular from Kurdish minority communities.48Human Rights Watch, ‘Events of 2024 – Iraq’, World Report 2025, January 2025, p 237. The destruction of civilian property and agricultural land noted earlier has further provoked a widespread sense of insecurity among the local population, compelling many to abandon their homes and livelihoods in search of safety.

Reports indicate that civilians attempting to return to their places of habitual residence, such as villagers of Bermiza in the Sidakan district, have also encountered obstruction and intimidation. On 2 and 7 April 2025, Turkish forces reportedly established military checkpoints and restricted access to local land, with explicit warnings that returnees would only be permitted to return within imposed boundaries. When villagers attempted to re-enter the area on 7 April, they were forcibly turned back.49CPT Iraqi Kurdistan, ‘Turkish Military Strikes Intensify Two Months into Ceasefire’ Community Peacemaker Teams, 12 May 2025. Turkey is said to be seeking to establish a security corridor across the Turkish-Iraq-Syrian border, while cooperating with Iraq in a road construction project that will directly connect the two States.50I. Okuducu, ‘Turkey’s Anti-PKK Operation and “Development Road” in Iraq Are Two Sides of the Same Coin’, The Washington Institute, 8 April 2024. Residents have described an environment of fear and coercion, with one claiming: ‘They will shoot you if you stay. … All they want is for us to leave these areas.’51S. Foltyn, ‘Turkey-PKK Conflict: Life inside Iraq’s “Forbidden Zone”’, BBC News, 30 April 2025.

In light of these realities, it is reasonable to conclude that displacement of Kurdish civilians often occurred under duress, threats, and a generalized fear of violence. The cumulative effect of these actions, including the destruction of property, the establishment of military installations, and the presence of Turkish troops, as well as direct threats against returnees, constitutes forced displacement within the meaning of IHL. Available evidence thus supports a finding that Türkiye committed a serious violation of the law.

Additional concerns arise from credible claims that the Iraqi Armed Forces may also have violated IHL. Kurdish farmers have on several occasions been prevented by Iraqi security forces from accessing their lands, despite a property restitution law that the Iraqi Parliament passed in early 2025.52‘PM Sudani Orders Probe into Iraqi Army Clashes with Farmers in Kirkuk’, RUDAW, 18 February 2025. The conduct, which indicates a breach of IHL by the Iraqi Armed Forces, has affected the Kurds in the KRI for several years, further undermining Kurdish groups’ access to their lands.53ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’. Certain incidents have been subject to an investigation ordered by the Iraqi government.54Ibid. But either they have not concluded, or the results of those investigations have not been made public.

Use of landmines

The continued presence of landmines and ERW in Iraq, in particular in areas previously controlled by Islamic State, constitutes a serious and ongoing threat to civilian life and a significant challenge to the implementation of IHL. The failure to direct landmines at specific military objectives violates the principle of distinction. When deployed in populated areas or locations frequently accessed by civilians, the munitions often have indiscriminate effects. Where they are employed without feasible precautions to limit their impact on civilians, they may also violate the principle of precautions in attack. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), these explosive devices continue to kill and maim indiscriminately in Iraq, obstructing civilian movement, limiting access to essential services, and impeding agricultural and pastoral livelihoods.55ICRC, ‘Landmines and Explosive Remnants Cast a Long Shadow over Iraq amid Recovery Efforts’, Press release, 2 April 2025.

The impact is particularly severe in areas previously contested between the Iraqi Armed Forces and Islamic State, where explosive contamination has compounded the humanitarian toll of armed conflict. Recorded incidents show that children are often among the victims. Between December 2024 and March 2025, explosive ordnance (defined broadly, and without disaggregation by type of explosive device) killed fourteen children of between two and seventeen years of age and seriously injured a further twelve.56‘Implementation of resolution 2732 (2024), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/323, 30 May 2025, para 55. Iraq recorded forty-four landmine casualties in 2024, down from fifty-six the year before.57Committee on Victim Assistance, ‘Preliminary Observation, Iraq: Status of Implementation – Victim Assistance’, Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 17–20 June 2025, para 9.

New use by Islamic State, which had earlier made massive use of anti-personnel mines of an improvised nature, was not, though, clearly in evidence during the reporting period. Iraq is a State Party to the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, which prohibits its armed forces from using any anti-personnel mine – defined as a munition that is designed or adapted to be activated by a person. This disarmament treaty does not bind Islamic State directly under international law, but the group is subject to the customary IHL principles of distinction and proportionality in attack, underpinned by the duty to take precautions to protect civilians.

Moreover, Iraq is also party to Amended Protocol II of 1996 to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, which does bind all parties to an armed conflict, including non-State armed groups.58Art 1(2), Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998. Iraq adhered to the 1996 Amended Protocol II in 2014. Although the protocol does not ban all use of anti-personnel mines, it specifically prohibits their indiscriminate use and requires that a party to an armed conflict take all feasible precautions to protect civilians from their effects.59Art 3(8) and (10), 1996 Amended Protocol II. Likewise, customary law requires that ‘when landmines are used, particular care must be taken to minimize their indiscriminate effects’.60ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 81: ‘Restrictions on the Use of Landmines’. While not an inherently indiscriminate weapon, the effects of anti-personnel mines, including those of an improvised nature as Islamic State employed very widely in the past in Iraq, are all too often felt by civilians. Iraq is obligated by the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention to clear and destroy all anti-personnel mines on its territory as soon as possible.61Art 5, Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction; adopted at Oslo, 18 September 1997; entered into force, 1 March 1999.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

Under customary IHL, special protection is afforded to several categories of civilians that face a specific risk of harm, such as women, children, refugees, and the displaced. The law provides for fundamental guarantees of bodily integrity and security for anyone in the power of a party to a conflict, prohibiting acts such as torture, inhumane or degrading treatment, collective punishments, sexual violence, enforced disappearance, and unfair trials.

Murder of civilians, arbitrary detention, torture, and inhuman treatment

Allegations of torture, extortion, and forced confessions by Iraqi security forces continue to raise serious concerns about Iraq’s obligations to comply with the absolute prohibition of torture and other forms of ill-treatment.62Amnesty International, ‘Iraq: People Held in Al-Jed’ah Centre Subjected to Torture and Enforced Disappearance after Arrests – New Investigation’, 29 October 2024; and Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Surging Unlawful Executions’. Further concerns persist as to Iraq’s compliance with the right of individuals to a fair trial.63ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 99: ‘Deprivation of Liberty’. Many of those detained were arrested based on an alleged affiliation with Islamic State, often without sufficient evidence or through ‘guilt by association’. Testimonies underscore the ongoing risks of false accusation, coerced confessions, collective punishment, and prolonged detention without due process, including of women and children.64Amnesty International, ‘Iraq: People Held in Al-Jed’ah Centre Subjected to Torture and Enforced Disappearance after Arrests – New Investigation’.

The absence of judicial guarantees is all the more concerning given that many individuals – most of whom are charged with terrorism offences65Human Rights Watch, ‘World Report 2025: Events of 2024’, Report, p. 240. – have been sentenced to death upon conviction and further that mass executions were performed during the reporting period. In September 2024 alone, the death penalty was imposed on twenty-one individuals.66Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘Scale and Cycle of Iraq’s Arbitrary Executions May Be a Crime against Humanity: Special Rapporteurs’, Press release, Geneva, 27 June 2024. These sentences, which followed flawed judicial procedures and using potentially coerced confessions to secure a conviction, are serious violations of IHL and may amount to war crimes.67Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

Moreover, the conditions of detention of those accused of affiliation with Islamic State continue to raise significant IHL concerns. Detention facilities in Iraq are severely overcrowded, typically with more than double the intended capacity. As a result, conditions are often dire, with inmates lacking access to adequate food, water, sanitation, and medical care.68Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Surging Unlawful Executions’, 19 November 2024; OHCHR, ‘Scale and Cycle of Iraq’s Arbitrary Executions May Be a Crime against Humanity: Special Rapporteurs’. Such conditions violate the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment under IHL, regardless of the conflict classification,69Common Art 3 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949; Arts 13 and 14, Geneva Convention III; Arts 27 and 32, Geneva Convention IV; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 90: ‘Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment’. and of international human rights law, which continues to apply in armed conflict.70Art 7, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; adopted at New York, 16 December 1966; entered into force, 23 March 1976; Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; adopted at New York, 10 December 1984; entered into force, 26 June 1987.

In response to growing domestic and international concern over wrongful detentions and the deteriorating conditions of incarceration, the Iraqi government has introduced a new amnesty law allowing certain prisoners convicted of terrorism offences to seek release or a retrial, or even to have their cases dismissed.71‘Iraq Frees over 19,000 Prisoners under New Amnesty, Including Some Ex-ISIL’, Al Jazeera, 13 May 2025. Ostensibly, this legislative measure aims to reduce prison overcrowding and address instances of false accusation.72Q. Abdul-Zahra, ‘Iraq’s Justice Minister Says Prisons Are at Double Their Capacity as Amnesty Law Takes Effect’, AP News, 5 May 2025. While the law’s introduction could address arbitrary or wrongful detentions and alleviate systematic overcrowding, its vague drafting and lack of procedural safeguards may also lead to impunity for perpetrators of grave crimes.73Ochab, ‘Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Personal Status and General Amnesty Laws’.

Islamic State also continued to abduct and murder civilians during the reporting period, albeit at a lower level than previously. For instance, on or around 1 September 2024, they abducted an individual in front of his house before killing him.74ACLED, ‘Data Export Tool’. During the week of 14 May 2025, members of Islamic State attacked shepherds, seizing all their mobile phones, kidnapping one who they later killed.75Ibid.

Protection of IDPs

As of 30 May 2025, more than one million Iraqis were internally displaced, with over 107,000 IDPs living in twenty camps in the KRI. Many Iraqi families and children with alleged connections to Islamic State are still in camps over the border in Syria.76‘Implementation of Resolution 2732 (2024), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/323, paras 33 and 39–40. Under customary IHL, applicable in all armed conflicts, displaced persons ‘have a right to voluntary return in safety to their homes or places of habitual residence as soon as the reasons for their displacement cease to exist.’77ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’.

Although Iraq is making efforts to repatriate its citizen from Syria and to ensure the safe return of IDPs to their homes, the displaced continue to face significant barriers, including limited access to documentation, a lack of opportunities for income generation, and social stigma and discrimination. Climatic factors, especially more frequent extremes of heat, along with funding shortfalls, have worsened the living conditions of those still in camps, reducing at the same time their prospects for return.78‘Implementation of Resolution 2732 (2024), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/323, para 41. The precarious conditions often come with heightened protection risks for women, girls, persons with disabilities, and other marginalized groups.79Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘NRC’s Operations in Iraq’, Fact Sheet, 2025. In line with Iraq’s obligations under customary IHL, efforts to facilitate the safe return of the many people displaced due to conflict need to be significantly strengthened.

Protection of civilians against forced displacement

As noted above, the reporting period evidences incidents of Kurdish communities being forcibly displaced by Turkish military operations on Iraqi territory, in circumstances constituting a serious violation of IHL. While the Iraqi government publicly condemns the military operations by the Turkish Armed Forces in Kurdish areas on its territory, it also pursues closer collaboration with Türkiye, including for counterterrorism. As part of the improved relationship between the two States, Iraq issued a joint statement with Türkiye labelling the PKK a ‘banned’ organization and a ‘security threat’. It has also agreed to cooperate with Türkiye in the construction of roads that will connect the two nations.80Okuducu, ‘Turkey’s Anti-PKK Operation and “Development Road” in Iraq Are Two Sides of the Same Coin’.

Insofar as these occur on the territory and under the authority of Iraq, Iraq bears heightened obligations under IHL to ensure respect for the law and a duty to investigate alleged war crimes on its territory, including unlawful forced displacement of civilians.81Common Art 1 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 144: ‘Ensuring Respect for International Humanitarian Law Erga Omnes’, http://bit.ly/46eTBcE; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’. The lack of efforts to halt and investigate alleged incidents of serious violations of IHL committed by Turkish Armed Forces is also a breach by Iraqi authorities of its obligations in this regard.

Protection of persons with disabilities

It is not known how many people are living with disabilities in Iraq, but the number is expected to be extremely high given the multiple armed conflicts over the past two decades. The widespread use of anti-personnel mines, including those of an improvised nature, has caused thousands of traumatic amputations of lower limbs. Persons with disabilities across the country, especially in the centre and north, whether their disability resulted from the conflicts or other causes, face an especially difficult future. In June 2025, in the context of the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, it was reported that Iraq had registered 34,249 mine victims. Iraq reported that rehabilitation centres exist in several governorates providing prosthetics, physiotherapy and psychological support, some of which are assisted by the ICRC and Humanity & Inclusion (HI).82Committee on Victim Assistance, ‘Preliminary Observation, Iraq: Status of Implementation’, paras 9, 19; HI, ‘Iraq’, accessed 30 August 2025, at: http://bit.ly/4lQK53S.

In 2024, the ICRC supported persons with physical disabilities to have effective access to physical rehabilitation services and assistive devices. The ICRC also supported civil society organizations in promoting the social and economic inclusion of people with physical disabilities within their communities – through adaptive sports, education and (self-) employment initiatives. In total, 13,795 women, men, and children benefited from physical rehabilitation at the ICRC-supported governmental centres or at the Erbil Physical Rehabilitation Centre. The ICRC organized and supported the second Iraqi amputee football tournament in Baghdad, featuring five teams with a total of 85 players from across Iraq, as part of its social inclusion programme.83ICRC, ‘Activity Report – Iraq 2024’, Report, Baghdad, 2025, p 10.

Protection of women and children

Women and children continue to face limited protection from and accountability for earlier conflict-related sexual violence. Many face severe difficulties when it comes to reintegration into their communities, due to cultural and societal norms, as well as stigma associated with sexual violence and fear of those with perceived ties to Islamic State.84M. Revkin, B. Krick, and R. Aldulaimi, ‘Reintegrating Iraqis Returning Home After Conflict’, Report, UNIDIR, pp 6–10. Yazidi women and girls who have children born of rape perpetrated during their captivity by Islamic State are particularly vulnerable, as are their children. Ostracised by the Yazidi communities, they live in NGO-run safe houses, without a clear path to a secure future.85Email from Sareta Ashraph, 13 October 2025.

The Iraqi government has shown little appetite to tackle these issues.86On the proposed law allowing marriage from the age of nine years, see: S. Ashraph, ‘Legalizing child marriage in Iraq: Stepping back from the brink’, Atlantic Council, 8 April 2025. In the context of Iraq, child marriage is frequently portrayed as a means to escape poverty.87M. Talal and H. Abdullah, ‘The end of women and children’s rights’: outrage as Iraqi law allows child marriage’, The Guardian, 22 January 2025. Such marriages increase the risk for girls of experiencing sexual and physical violence, along with adverse health implications, both physical and mental, and often result in the deprivation of access to education and employment opportunities.88Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Personal Status Law Amendment Sets Back Women’s Rights’, 10 March 2025.

Furthermore, as noted above, conflict-related incidents continue to be prosecuted under Iraq’s anti-terrorism law, but this legislation does not acknowledge conflict-related sexual violence as a form of terrorism, thereby creating a considerable gap in the legal capacity to prosecute Islamic State affiliates for such acts. In January 2025, the Iraqi Parliament enacted legislation granting amnesty to specific prisoners convicted under the terrorism law.89Anti-Terrorism Law (No 13) of 2005. This development has reportedly adversely affected segments of the Iraqi population, particularly women and girls, as well as minority groups targeted by the Islamic State.90Ochab, ‘Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Personal Status and General Amnesty Laws’.

Further concerns regarding the protection of women and girls have emerged following the termination of the mandate of the UN Protection Cluster in Iraq, which was led by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The areas of responsibility included gender-based violence, child protection, mine action, and housing, land, and property. All these functions were deactivated in December 2022.91Global Protection Cluster, ‘Iraq: Cluster Operation’.

Treatment of the dead

The reporting period attests to the discovery and continued presence of mass graves across Iraq. Recent estimates suggest that these graves contain the remains of as many as 400,000 people.92‘Iraq’s Mass Graves Contain 400,000 Bodies: Observers’, Basnews, 6 November 2024. Many sites are believed to contain the bodies of victims in earlier armed conflicts and concern serious violations of IHL.93Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Exhume Mass Grave Sites to Ensure Justice’, News release, 13 August 2024. In this context, there is a duty to investigate conduct that may amount to a war crime.94Art 49, Geneva Convention I; Art 50, Geneva Convention II; Art 129, Geneva Convention III; Art 146, Geneva Convention IV; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’. IHL obligates Iraq to uncover the truth, prosecute those responsible, and ensure justice and reparations for the victims.

- 1A. Mehvar et al, ‘Middle East Overview: January 2025’, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), 4 July 2025.

- 2N. Ezzeddine, ‘Q&A – Disbanding the PKK: A Turning Point in Turkey’s Longest War?’, ACLED, 25 July 2025.

- 3‘Turkey and Iraq Deepen Ties with Landmark Agreements and Regional Dialogue’, Syriac Press, 9 May 2025.

- 4Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR), ‘UNHCR IRAQ Update March 2025’, 24 April 2025.

- 5Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘NRC’s Operations in Iraq’, Fact Sheet, May 2025, p 1.

- 6UNITAD, ‘Statement from the Acting Special Adviser and Head of UNITAD on the Conclusion of the UNITAD Mandate’, Baghdad, 16 September 2024.

- 7Since UNITAD’s closure, European prosecutors bringing cases against Islamic State-affiliated individuals are said to have experienced significant difficulties in accessing material in its database, which is held by the UN Office of Legal Affairs in New York. Information provided in email from Sareta Ashraph, 13 October 2025.

- 8Anti-Terrorism Law (No 13) of 2005), unofficial English translation at: http://bit.ly/4nbcfrG.

- 9E. U. Ochab, ‘Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Personal Status and General Amnesty Laws’, Forbes, 26 January 2025.

- 10Ibid.

- 11The material jurisdiction of the Protocol is limited to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups.…’ [added emphasis]. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II of 1977.

- 12International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’.

- 13ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 14

- 15

- 16ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances.

- 17ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 54: ‘Attacks against Objects Indispensable to the Survival of the Civilian Population’.

- 18

- 19‘Persistent Turkish Military Strikes Target Civilian Residences in Iraqi Kurdistan’, Medya News, 25 September 2024.

- 20T. Krüger, ‘As Turkey Escalates Attacks in Iraq, Kurdish Journalists Are Becoming Targets’, Truthout, 9 September 2024.

- 21One dunam equals approximately 900 square metres.

- 22‘Turkish artillery causes large wildfire in Iraq’s Duhok’, Shafaq News, 20 June 2025.

- 23S. Martany, ‘Iraq’s Displaced Kurds Hope to Return Home after Turkey’s Kurdish Militants Declare a Ceasefire’, Associated Press News, 2 March 2025.

- 24K. Faidhi Dti, ‘“We Were Surrounded by Fire”: Duhok Villagers Battle Blazes Blamed on Turkish Bombs’, RUDAW, 8 August 2024.

- 25Martany, ‘Iraq’s Displaced Kurds Hope to Return Home after Turkey’s Kurdish Militants Declare a Ceasefire’.

- 26‘Turkey Attempts to Neutralise PKK Tunnels in Iraq despite Dissolution of Kurdish Militant Group’ France 24, 10 July 2025.

- 27‘TI113 – September 10, 2024’, Airwars, 10 September 2024.

- 28UN, ‘United Nations in Iraq Condemns Attack in IDP Camp in Duhok’, Press release, 1 July 2025.

- 29‘Turkey Expands Military Operations in Iraq as Cross-Border Attacks Intensify’, Medya News, 20 April 2025.

- 30ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’.

- 31Community Peacemaker Teams, ‘The Continuation of Turkish Military Operations in Iraqi Kurdistan Despite PKK’s Unilateral Ceasefire’, 2 April 2025.

- 32‘Turkey Attempts to Neutralise PKK Tunnels in Iraq despite Dissolution of Kurdish Militant Group’.

- 33Community Peacemaker Teams, ‘The Continuation of Turkish Military Operations in Iraqi Kurdistan Despite PKK’s Unilateral Ceasefire’.

- 34

- 35ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants’; and Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’.

- 36ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 6: ‘Civilians’ Loss of Protection from Attack’. The accompanying commentary states that in NIACs, ‘the issue of doubt has hardly been addressed in State practice, even though a clear rule on this subject would be desirable as it would enhance the protection of the civilian population against attack.’ One ‘cannot automatically attack anyone who might appear dubious….’ The same approach with respect to IACs ‘seems justified’ in NIACs.

- 37

- 38‘TI108 – July 8, 2024’, Airwars, 8 July 2024.

- 39‘TI111 – August 23, 2024’, Airwars, 23 August 2024.

- 40Reporters Without Borders, ‘RSF alarmed by surge in violence against journalists in Iraqi Kurdistan’, RSF, 21 August 2024.

- 41Ibid.

- 42T. Krüger, ‘As Turkey Escalates Attacks in Iraq, Kurdish Journalists Are Becoming Targets’.

- 43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 34: ‘Journalists’.

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48Human Rights Watch, ‘Events of 2024 – Iraq’, World Report 2025, January 2025, p 237.

- 49CPT Iraqi Kurdistan, ‘Turkish Military Strikes Intensify Two Months into Ceasefire’ Community Peacemaker Teams, 12 May 2025.

- 50I. Okuducu, ‘Turkey’s Anti-PKK Operation and “Development Road” in Iraq Are Two Sides of the Same Coin’, The Washington Institute, 8 April 2024.

- 51S. Foltyn, ‘Turkey-PKK Conflict: Life inside Iraq’s “Forbidden Zone”’, BBC News, 30 April 2025.

- 52‘PM Sudani Orders Probe into Iraqi Army Clashes with Farmers in Kirkuk’, RUDAW, 18 February 2025.

- 53ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’.

- 54Ibid.

- 55ICRC, ‘Landmines and Explosive Remnants Cast a Long Shadow over Iraq amid Recovery Efforts’, Press release, 2 April 2025.

- 56‘Implementation of resolution 2732 (2024), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/323, 30 May 2025, para 55.

- 57Committee on Victim Assistance, ‘Preliminary Observation, Iraq: Status of Implementation – Victim Assistance’, Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 17–20 June 2025, para 9.

- 58Art 1(2), Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998. Iraq adhered to the 1996 Amended Protocol II in 2014.

- 59Art 3(8) and (10), 1996 Amended Protocol II.

- 60

- 61Art 5, Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction; adopted at Oslo, 18 September 1997; entered into force, 1 March 1999.

- 62Amnesty International, ‘Iraq: People Held in Al-Jed’ah Centre Subjected to Torture and Enforced Disappearance after Arrests – New Investigation’, 29 October 2024; and Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Surging Unlawful Executions’.

- 63

- 64Amnesty International, ‘Iraq: People Held in Al-Jed’ah Centre Subjected to Torture and Enforced Disappearance after Arrests – New Investigation’.

- 65Human Rights Watch, ‘World Report 2025: Events of 2024’, Report, p. 240.

- 66Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘Scale and Cycle of Iraq’s Arbitrary Executions May Be a Crime against Humanity: Special Rapporteurs’, Press release, Geneva, 27 June 2024.

- 67Common Article 3, Geneva Conventions; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 68Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Surging Unlawful Executions’, 19 November 2024; OHCHR, ‘Scale and Cycle of Iraq’s Arbitrary Executions May Be a Crime against Humanity: Special Rapporteurs’.

- 69Common Art 3 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949; Arts 13 and 14, Geneva Convention III; Arts 27 and 32, Geneva Convention IV; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 90: ‘Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment’.

- 70Art 7, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; adopted at New York, 16 December 1966; entered into force, 23 March 1976; Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; adopted at New York, 10 December 1984; entered into force, 26 June 1987.

- 71‘Iraq Frees over 19,000 Prisoners under New Amnesty, Including Some Ex-ISIL’, Al Jazeera, 13 May 2025.

- 72Q. Abdul-Zahra, ‘Iraq’s Justice Minister Says Prisons Are at Double Their Capacity as Amnesty Law Takes Effect’, AP News, 5 May 2025.

- 73Ochab, ‘Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Personal Status and General Amnesty Laws’.

- 74ACLED, ‘Data Export Tool’.

- 75Ibid.

- 76‘Implementation of Resolution 2732 (2024), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/323, paras 33 and 39–40.

- 77ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 132: ‘Return of Displaced Persons’.

- 78‘Implementation of Resolution 2732 (2024), Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/323, para 41.

- 79Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘NRC’s Operations in Iraq’, Fact Sheet, 2025.

- 80Okuducu, ‘Turkey’s Anti-PKK Operation and “Development Road” in Iraq Are Two Sides of the Same Coin’.

- 81Common Art 1 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 144: ‘Ensuring Respect for International Humanitarian Law Erga Omnes’, http://bit.ly/46eTBcE; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’.

- 82Committee on Victim Assistance, ‘Preliminary Observation, Iraq: Status of Implementation’, paras 9, 19; HI, ‘Iraq’, accessed 30 August 2025, at: http://bit.ly/4lQK53S.

- 83ICRC, ‘Activity Report – Iraq 2024’, Report, Baghdad, 2025, p 10.

- 84M. Revkin, B. Krick, and R. Aldulaimi, ‘Reintegrating Iraqis Returning Home After Conflict’, Report, UNIDIR, pp 6–10.

- 85Email from Sareta Ashraph, 13 October 2025.

- 86On the proposed law allowing marriage from the age of nine years, see: S. Ashraph, ‘Legalizing child marriage in Iraq: Stepping back from the brink’, Atlantic Council, 8 April 2025.

- 87M. Talal and H. Abdullah, ‘The end of women and children’s rights’: outrage as Iraqi law allows child marriage’, The Guardian, 22 January 2025.

- 88Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Personal Status Law Amendment Sets Back Women’s Rights’, 10 March 2025.

- 89Anti-Terrorism Law (No 13) of 2005.

- 90Ochab, ‘Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Personal Status and General Amnesty Laws’.

- 91Global Protection Cluster, ‘Iraq: Cluster Operation’.

- 92‘Iraq’s Mass Graves Contain 400,000 Bodies: Observers’, Basnews, 6 November 2024.

- 93Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq: Exhume Mass Grave Sites to Ensure Justice’, News release, 13 August 2024.

- 94Art 49, Geneva Convention I; Art 50, Geneva Convention II; Art 129, Geneva Convention III; Art 146, Geneva Convention IV; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 158: ‘Prosecution of War Crimes’.