Conflict Overview

Mozambique continues to be involved in an armed conflict in its northern Cabo Delgado province, although violence has also spread into neighbouring Niassa province. In total, 6,000 people have been killed and countless others seriously injured since the conflict broke out in 2017. The Mozambican Armed Forces (FADM) are supported by troops from other African nations in their operations against Islamic State Mozambique Province (ISM), also known as Ahlu Sunna Wal-Jama. Authorized communal militias of mainly demobilized soldiers (‘Local Forces’) fight sporadically against ISM.

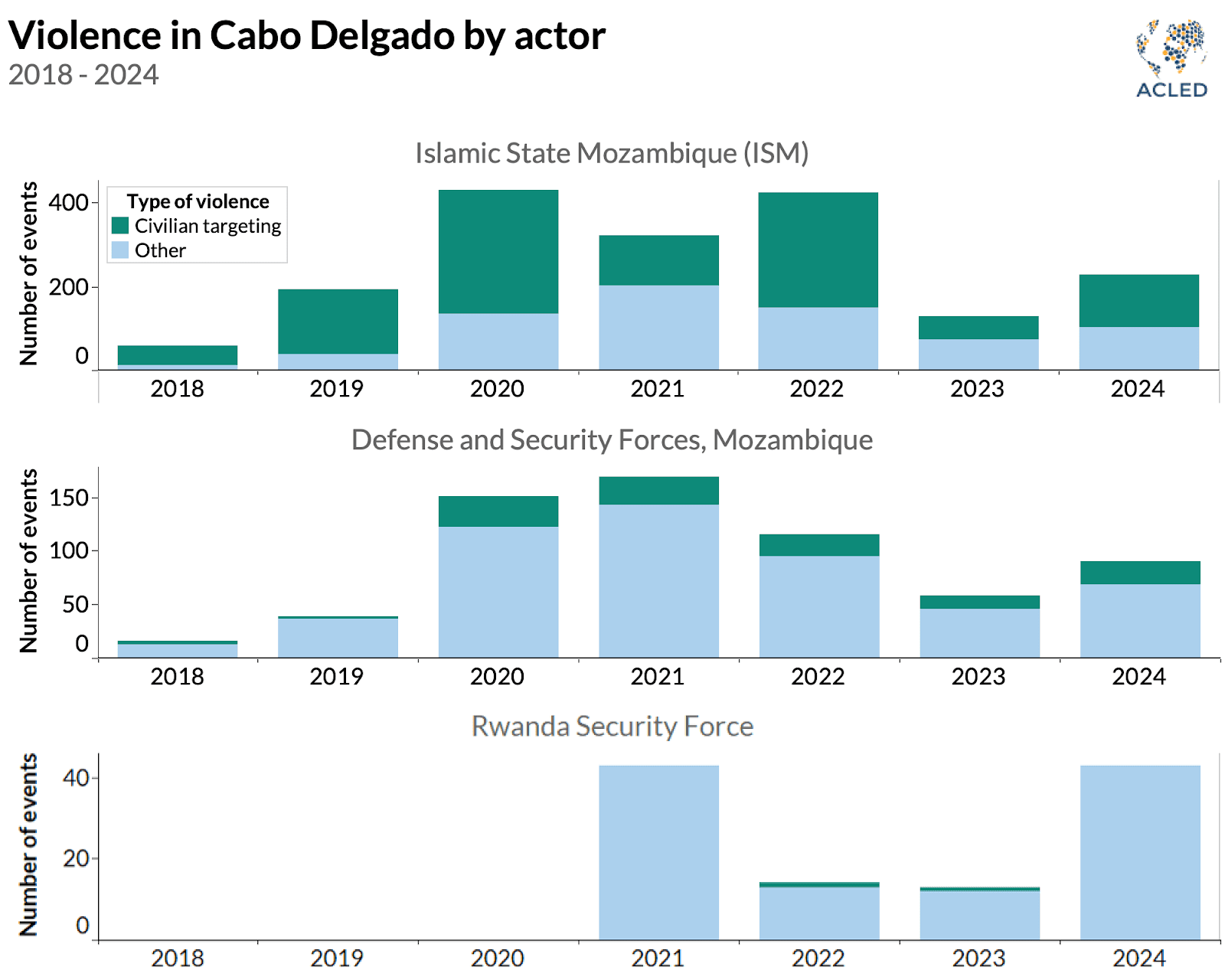

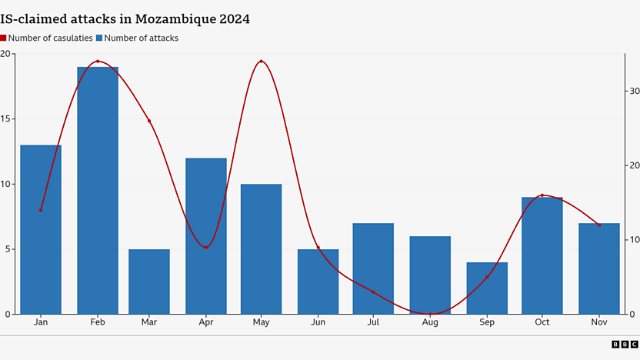

The conflict started in 2017 following an encounter between local law enforcement and affiliates of an Islamist group designated locally as ‘Al-Shabaab’, which had launched attacks on police stations and briefly occupied the port town of Mocímboa da Praia. Although the intensity of the conflict in Cabo Delgado has waxed and waned over time, widespread attacks against civilians and civilian objects by ISM have been a constant feature. More recently, violations have involved pillage (the looting of private property) and hostage-taking of civilians (abduction for ransom). Fighting in the conflict was particularly intense during the first half of 2025, with May of that year recording the sharpest rise in casualties since June 2022. ISM increased its territorial dominance in several parts of northern Cabo Delgado in the course of 2025.

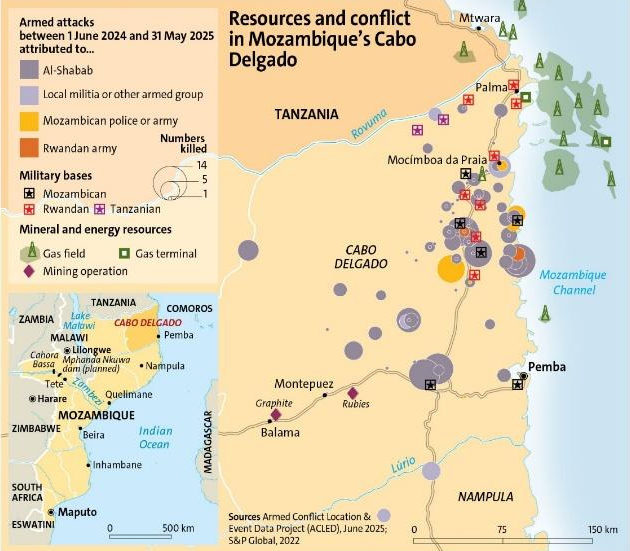

The FADM has also engaged in abductions of those suspected to be affiliates of ISM, including of fishermen at sea for this reason. In addition, notwithstanding the fact that Rwandan forces supporting the FADM have officially prioritized civilian protection, their actions during the reporting period may have put civilians at risk, whether through inaction or delayed reaction. This has been seen in particular on the N380, a highway running from Pemba, the provincial capital in the south, to the port town of Mocímboa da Praia in the north. The N380 is critical to the flow of people and goods through the province, as well as to securing a major liquid natural gas (LNG) project at Afungi. But evidence suggests Rwandan troops may often have been ‘unresponsive’ when civilians were being attacked or threatened.1‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data project (ACLED), 25 April 2025.

Hostilities with ISM have led to greatly increased internal displacement. Despite recorded returns, in May 2025, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported more than 700,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Mozambique, most in the north of the country. In 2024, for the first time, Norwegian Refugee Council described Mozambique as ‘one of the world’s most neglected displacement crises’.2Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘The world’s most neglected displacement crises 2024’, 3 June 2025. What is more, tensions with host communities worsened towards the end of the reporting period; on occasion, Local Forces militia were instructed by local authorities to repel IDPs by force. IDPs who return home face renewed insecurity and little to no external assistance. Indeed, local NGOs have spoken of the difficulties they encounter in seeking to assist those affected by the conflict in Cabo Delgado.3See eg: Lusa, ‘ONG alerta para dificuldades em prestar assistência às vítimas de Moçambique’, Publico, 11 August 2025.

A dedicated counterterrorism think-tank in the United States, the Soufan Center, has suggested that the Mozambican government’s current approach to counterterrorism risks ‘deepening local grievances by prioritizing economic interests over addressing the root causes of conflict’.4The Soufan Center, ‘Islamic State in Mozambique Rearing Its Head Again’, 15 January 2025. The lack of government services, widespread poverty, rising ethno-sectarian tensions, and lingering land disputes amount to something of a ‘perfect storm’ for a rebellion. ISM has leveraged entrenched grievances in the Mozambican population about socio-economic inequalities to destabilize the region. The wave of post-election violence following the disputed 2024 presidential elections strengthened ISM narratives, facilitating its extension of territorial control.5Ibid.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

There is a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) between Mozambique (supported by the armed forces of Rwanda and Tanzania) and ISM. Mozambique and its allies are States Parties to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949. Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions along with customary international humanitarian law (IHL) apply to the armed conflict. Mozambique is also a State Party to Additional Protocol II of 1977, whose requirement for sustained territorial control by an organized armed group is met by ISM in Cabo Delgado. Rwanda and Tanzania are both parties to Additional Protocol II and that treaty similarly applies to their actions.

Until the end of 2024, South Africa (also a party to Additional Protocol II) deployed troops from its defence forces, the SANDF. In addition, from 2021 to mid-July 2024, the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) had contributed troops to fight alongside the Mozambican military.6SAMIM concluded its mission on 15 July 2024. ‘Actor Profile: SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM)’, Cabo Ligado, 2 May 2024; Bofin, ‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’; ‘Withdrawal of the Southern African Development Community Mission In Mozambique (SAMIM) Force Members from Cabo Delgado’, Southern African Development Community, 5 April 2024; A. Massango, ‘SAMIM formally withdraws from Cabo Delgado’, AIM, 4 July 2024. Collectively, these forces have endeavoured, albeit with varying degrees of success, to contain ISM.7See generally: P. Pigou and J. Opperman, ‘Conflict in Cabo Delgado: From the Frying Pan into the Fire?’, Report, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, 15 June 2021; and International Crisis Group, ‘Stemming the Insurrection in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado’, Africa Report No 303, 11 June 2021. Greater progress has been made in the south of Cabo Delgado than in the north.8International Organization for Migration (IOM), ‘Mozambique Crisis Response Plan Jan-Dec 2025’, 27 June 2025, p 5.

SAMIM, for the most part, operated in parallel with the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) and the Rwanda National Police (RNP). The RDF and RNP, which are known as the Rwandan Security Forces (RSF), remain operational in the province. The RSF had more than 4,000 troops in northern Mozambique during the reporting period – an exceptionally large, and well-equipped force.9Bofin, ‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’. The RSF had been dispatched to Cabo Delgado in 2021, a month prior to SAMIM’s deployment, in the wake of an ISM attack on the town of Palma. This attack caused the suspension of the huge LNG project sited nearby.10‘TotalEnergies plans to restart Mozambique LNG project by August 2025’, Club of Mozambique, 22 May 2025; and C. Howe, ‘WGC TotalEnergies CEO aims to lift force majeure on Mozambique LNG project’, Reuters, 20 May 2025. In addition, the Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF) has fought ISM in Cabo Delgado’s Nangade district since 2021 – first as part of SAMIM and, since October 2022 (after SAMIM’s withdrawal), through a bilateral agreement with the Mozambican government.11‘Actor Profile: Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF)’, Cabo Ligado, 29 May 2024.

Although not a party to the NIAC in Cabo Delgado, the European Union (EU) has been providing training and capacity-building to the Mozambican military, aiming to support the FADM in their efforts to restore safety and security to the province. The support, which began in October 2021, has focused on training selected army units for organization into 11 ‘Quick Reaction Forces’. The mandate of the EU Military Assistance Mission Mozambique (EUMAM Moz), which includes instruction in both IHL and international human rights law, has been extended to June 2026.12‘About EUMAM Moz’, EUMAM Mozambique, 8 January 2025.

Parties to the Non-International Armed Conflict

Mozambique v Islamic State Mozambique Province (ISM)

Mozambique is supported by Rwanda (the Rwandan Security Forces, RSF) and Tanzania (TPDF). During the reporting period, it was also supported until 15 July 2024 by SAMIM, a force comprising troops from Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. After SAMIM’s withdrawal, the SANDF remained in Mozambique until December 2024.

The Local Forces militia are not a party to the NIAC. Although they were authorized by the Mozambican government in 2023 to fight ISM, they are not sufficiently organized to meet the requirements of IHL. Members of Local Forces are best understood as individuals directly participating in hostilities (when they meet the criteria for this status under IHL, which involves actual or potential harm to an enemy resulting directly from their actions).

The NIAC in Mozambique has a distinctly economic element, with fears in Cabo Delgado that international companies will profit and the local businesses and communities will lose out. Indeed, the armed conflict as a whole is perceived to be driven by discontent over exploitation of large-scale natural gas reserves.14C. Haenlein, J. de Deus Pereira, M. Jones and L. O’Shea, ‘Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Mozambique A Bottom-Up Analysis of Local Perceptions’, Whitehall Report 1-25, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), London, June 2025, p 28. This economic perspective does not preclude the existence of an armed conflict under IHL.

Most of the nation’s natural gas reserves, some five trillion cubic metres’ worth, are concentrated in the northern province, an attraction to many multinational companies. Thus, TotalEnergies (France), ExxonMobil (United States), Eni (Italy), and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) have all invested in strategic concessions to explore and then share gas production with the Mozambican government. Gemfields (United Kingdom) is a majority owner of Montepuez Ruby Mining (MRM), which operates one of the world’s largest ruby mines.15C. Marin, ‘Resources and conflict in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado’, Le Monde diplomatique, 5 July 2025. There is also artisanal gold mining in Cabo Delgado.

In May 2025, TotalEnergies announced its intention to restart operations at the US$20 billion liquified natural gas project in the Afungi peninsula in the east of the province, which by then had lain dormant for almost four years. But despite the country’s mineral and natural resource wealth, local business owners fear that security restrictions will hinder supply by local services to the TotalEnergies LNG project.16LUSA, ‘Mozambique: Cabo Delgado businesses fear being left out of TotalEnergies’ project’, Club of Mozambique, 4 August 2025. TotalEnergies also faces a potential criminal case for its actions during the 2021 Palma attack. On 14 March 2025, French prosecutors opened an investigation into the company over alleged neglect of contractor safety. TotalEnergies has reiterated its denial of any wrongdoing.17International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Database, March 2025. Beyond any criminal responsibility, questions remain about the financial viability of the LNG project – and the security of those who will be working on the site.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

During the reporting period, there were consistent reports of ISM attacking civilians and civilian objects – health facilities, humanitarian convoys, and tourism sites – across Cabo Delgado. This occurred in parallel with continued targeting of Mozambican and foreign military personnel by the group (acts that are not generally unlawful under IHL). Violence has also spread into neighbouring Niassa province, especially since May 2025.18International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Database, May 2025.

ISM often focuses its violence on Christians, resulting in displacement by these communities during and following attacks. On occasion, it is enough that the presence of ISM fighters nearby is rumoured. The fears appear well founded. In November 2024, for instance, ISM announced publicly that it had attacked civilians and villages described as Christian in Mocímboa da Praia and Muidumbe districts, with their fighters either beheading or shooting dead four civilians in three separate attacks. They also reportedly burned down twelve homes – some in the village of Mbau in Mocímboa da Praia and in a locality known as Maniania in Muidumbe.19‘Briefing: IS claims spate of deadly attacks on troops, civilians in Mozambique’, BBC Monitoring, 11 November 2024. In 2021, the United States designated ISM as a foreign terrorist organization, naming it ISIS-Mozambique.20The Soufan Center, ‘Islamic State in Mozambique Rearing Its Head Again’.

In a small number of areas, however, mostly in Macomia and Quissanga districts, the United Nations has found that ISM has adopted a ‘winning hearts and minds’ approach, avoiding violence against and intimidation of the civilian population, and paying for items before leaving – without engaging in violence.21UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’, 10 July 2025. By the end of 2024, ISM tactics were being described as increasingly sophisticated, calculated, and well-executed.22Security Council Report, ‘Counter-Terrorism, January 2025 Monthly Forecast’, 30 December 2024.

The FADM has also been accused of attacking civilians, albeit to a considerably lower extent than ISM. The Mozambican army stands accused of intimidation and abduction of those it suspects of having links to ISM. The FADM is also believed to have killed civilians, including fishermen at sea, as illustrated below. Adding to this violence, community members in Cabo Delgado allege the authorities of routine corruption, involving, for instance, supply of food and weapons to ISM and release of suspected members in exchange for bribes.23Haenlein et al, ‘Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Mozambique A Bottom-Up Analysis of Local Perceptions’, p 27.

There has been little suggestion that Rwandan forces have targeted civilians during their military operations in the province. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project suggests that Rwanda’s central role in adopting and promoting the Kigali Principles on the Protection of Civilians helps to explain its low level of civilian targeting – although the Principles were devised for UN peacekeeping missions, ‘they seem to have also shaped how Rwandan forces undertake counter-insurgency in Mozambique’.24Bofin, ‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’ That said, use by the RSF of combat helicopters from August 2024 provoked fears of significant civilian harm.25Cabo Ligado, ‘Cabo Ligado Update: 22 July–4 August 2024’, ACLED, 8 August 2024. Moreover, in March 2025, a senior figure in the Local Force militia claimed that Rwandan forces in the province had become unwilling to engage with ISM militarily. He claimed that their troops often turned up hours after an attack, even when they were nearby. He noted how ISM is based close to the N380 highway and ‘take advantage of any opportunity’ to attack.26Bofin, ‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’

Although the needs of the civilian population are acute, the Mozambican government has made the delivery of humanitarian aid increasingly difficult in certain respects, such as by delaying the granting of work permits, credentials, and humanitarian visas. These were affecting at least six international NGOs as of June 2025 (and probably more, due to under-reporting).27OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’, 10 July 2025. Increased military checkpoints by both ISM and the security forces in 2025 have restricted movement in Cabo Delgado, further delaying aid deliveries.28OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’, 12 June 2025. It is a customary IHL rule in both IAC and NIAC that the parties to an armed conflict must allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief for civilians in need, where the aid is impartial in character and conducted without any adverse distinction. This duty is subject to the parties’ right of control, but consent may not be arbitrarily denied.29International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’.

These challenges and impediments have had significant humanitarian consequences. Across Mozambique, between October 2024 and March 2025, 4.9 million people were calculated to be facing high levels of acute food insecurity – at or above crisis level, according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). In addition, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported a sharp rise in severe acute malnutrition cases in March and April 2025, with more than 5,000 children admitted for treatment in March alone — the highest number in recent years and well above the five-year average.30OCHA, ‘Mozambique 2025 Humanitarian Response – Drought Appeal, as of 31 May 2025’, 2 July 2025. By June 2025, escalating conflict across northern Mozambique, funding shortfalls, cholera outbreaks, and the aftermath of three consecutive cyclones were severely constraining humanitarian efforts and exacerbating civilian suffering. Many people have been displaced multiple times and urgently need food, water, and shelter.31OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Cabo Delgado, Nampula & Niassa Humanitarian Snapshot, As of June 2025’, 4 July 2025.

Civilian Objects under Attack

ISM has regularly attacked civilian objects in particular. Under customary IHL in both IAC and NIAC, attacks may only be directed against military objectives and must not be directed against civilian objects.32ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives.33ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. Special protection is afforded to medical units, such as hospitals and other medical facilities.34ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28: ‘Medical Units’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.35ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralisation must offer a definite military advantage in the prevailing circumstances. Pillage – the looting of private property – is strictly prohibited under IHL.36Art 4(2)(g), Additional Protocol II of 1977; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 52: ‘Pillage’.

Attacks against health facilities

Health infrastructure in Cabo Delgado has been severely affected by the armed conflict. By July 2025, only one health centre in Macomia district in the centre of the province was still functional, down from the seven that existed before the conflict. What is more, the facility in Macomia town that did remain open was overwhelmed by the needs of the population. Macomia was attacked by ISM in May 2024, forcing Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and other humanitarian organizations to stop or suspend activities. MSF was gradually able to resume operations in April 2025.37MSF, ‘As Cabo Delgado experiences an alarming rise in violence, access to healthcare for communities in vulnerable circumstances is being severely compromised’, Press release, Pemba, 16 July 2025.

In a press release, MSF called for better protection of health facilities and medical workers against the violence. ‘With the increase in displacements, many people have come to seek refuge in Macomia, overwhelming the only functional health center’, MSF doctor Emerson Finiose said. ‘We’re struggling to do medical referrals. We must prioritize the most severe cases, leaving a significant gap in care for the rest of the community.’38Ibid.

The situation in Macomia, which illustrates the fragility of the health system in Cabo Delgado, has been repeated across the three other districts where MSF is present – Mocímboa da Praia, Mueda, and Palma. Since the conflict began, more than half of the province’s health facilities have been completely or partially destroyed, according to official data. The situation worsened when Cyclone Chido struck the south of Cabo Delgado in December 2024. The violence has led to further deterioration in health care provision. In 2025, MSF was forced to suspend outreach activities five times due to insecurity, for at least two weeks at a time, particularly in Macomia and Mocímboa da Praia.39Ibid. Under customary IHL in all armed conflicts, facilities dedicated to medical purposes must be respected and protected in all circumstances.40ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28. See also Art 11, Additional Protocol II of 1977.

Attacks against humanitarian aid

ISM has regularly targeted aid supplies. On 25 May 2025, a non-State armed group, believed to be ISM, looted a humanitarian truck in Rio Muera (in Mocímboa da Praia), leading to a temporary halt of movements along the N380. By 29 May, one international NGO had suspended food distributions in Macomia, relocating two international staff members to Pemba due to increased threats to its staff. But on occasion local communities, frustrated at what they perceive as poor aid distribution, have also assailed humanitarian relief. On 23 May 2025, humanitarian supplies were looted in Chiúre, highlighting the rising tensions.41OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

Attacks against mines

ISM has launched multiple attacks on mines across the province. In early April 2025, for instance, ISM targeted artisanal gold mining in Ancuabe, reportedly occupying the site for several days. This was part of a funding drive by the group, which may be partly related to Islamic State’s setbacks in Somalia (see the entry on Somalia), as Al-Shabaab, the Somalia-based Islamic State affiliate, previously distributed funds throughout Africa, including to ISM.42International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Database, April 2025.

Attacks against tourism sites

In April 2025, as part of the group’s fundraising – and propaganda – ISM launched a series of attacks in Niassa province, which is to the west of Cabo Delgado. On 19 April, a group of 40 ISM fighters stormed the luxury Chapungu-Kambako Safaris hunting camp in the Niassa Special Reserve. The militants beheaded two workers and took several hostages – both war crimes – and occupied the site for five days. The rebels demanded a ransom of three million meticais (€40,000) for the release of four workers. After this demand was rejected, the militants set fire to the main camp. The attacks secured ISM considerable attention in international media.43‘IS-Mozambique Launches Wave of High-Profile Attacks’, Africa Defense Forum, 17 June 2025, quoting Fernando Lima, a researcher with ACLED’s Cabo Ligado conflict observatory.

Attacks against commercial shipping

The first attack on a foreign commercial ship, apparently mounted by ISM, occurred in May 2025. The group targeted a Russian oceanographic vessel off Tambuzi Island, near Mocímboa da Praia, marking ‘the first major terrorist operation at sea in Mozambique’.44N. Mendes, ‘Insurgents Attack Russian Vessel off Mocímboa da Praia’, The Mozambique Times, 13 May 2025. The piratical attack involved the Atlantida K-1704 being approached by two speedboats when it was four nautical miles east of the island. The ship and its crew escaped by heading into deeper waters, out of reach of the attackers’ boats. While ISM has previously targeted fishermen around the islands of Mocímboa da Praia and Macomia (Quirimbas Archipelago), this was the first known attack on a foreign-flagged vessel. Sources in the Mozambican Navy, however, argued that the likelihood of similar attacks was low, given the limited capacity of ISM to conduct maritime operations.45Ibid.

Civilians under Attack

Aside from certain instances where ISM has respected the members of local communities, in general its forces have consistently targeted civilians. After a sustained decrease in ISM violence for the first eleven months of 2023, when most of its attacks targeted military forces, in December 2023 and throughout 2024, the conflict dynamics changed drastically. This was seen not only in the regularity and intensity of attacks, but also in the group’s modus operandi, which increasingly involved attacks directed against civilians and civilian infrastructure46.Global Protection Cluster, ‘Mozambique Protection Analysis Update’, 27 February 2025. The departure of SAMIM in July 2024 saw a new wave of deadly attacks by ISM in Chiure, Macomia, and Nangade districts, which led thousands of civilians to flee in search of safety.47Human Rights Watch, ‘Mozambique’, World Report 2025.

The situation continued to deteriorate in 2025. May saw the sharpest monthly rise in violence in the province since June 2022, affecting more than 134,000 people. Of the 61 ‘security incidents’ recorded in May 2025 by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), at least 38 involved attacks on civilians. Between January and June, ISM is believed to have abducted up to 300 people. Violence centred on Ancuabe, Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia, Montepuez, Muidumbe, and Palma, but also spread into Mecula district in Niassa province, displacing about 2,000 people in the process.48OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

Murder and abduction of civilians

Violence against civilians thus became widespread during the reporting period. Among the five most severe protection risks identified by the Global Protection Cluster for Mozambique in 2024 were attacks on civilians and unlawful killings and abduction of civilians, and the use, recruitment, and association of children in armed forces and groups. Also an increasing threat (discussed below) was conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence.49Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province, Protection Analysis Update’, January 2025, p 2. Compared to 2023, recorded civilian casualties in 2024 were up by 89 per cent (rising from 144 to 272); the number of people abducted increased by 224 per cent (from 101 to 328), while those struck by explosive devices increased by 305 per cent (albeit from a low base) – going up from 17 to 69).50Ibid, p 3.

This pattern continued in 2025. In June, OCHA reported that attacks in the central and northern districts of Macomia, Meluco, and Muidumbe killed 26 civilians and resulted in a further 47 being abducted.51OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’. ISM fighters raided several villages and clashed with security forces. On 6–8 June, for instance, ISM targeted Magaia village in Muidumbe district, abducting six civilians. Local Forces militants later forced ISM to retreat, killing an unconfirmed number of the group’s fighters while losing one of their own.52International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Conflict Tracker, June 2025.

Attacks against fishermen

The Mozambican armed forces have also fired on fishing vessels on multiple occasions, including during and following the reporting period. On 5 July 2025, a FADM marine patrol opened fire on three fishing boats off Pangane, killing at least three men and injuring at least four more. The reason for the attack is not known but it may be related to the hostilities with ISM around Quiterajo. Video clips showed two of the wounded being rushed to Mucojo by vehicle, where they were treated at a Rwandan health facility before being transferred to Macomia town. Sources identified the boat as belonging to the FADM. A spokesperson for the armed forces, Colonel Benjamin Chabualo, told Zitamar News that they were aware of the incident but did ‘not yet have any official information on this concerning matter’.53‘Mozambican navy accused of killing fishermen off coastal‘ Macomia, Zitamar News, 7 July 2025.

On 16 July, the FADM navy fired on fishers off the coast of Macomia at least twice, killing at least six people. This brought the total of civilian killings by FADM at sea to 110 since 2020, according to ACLED. The killings occurred as fighting between FADM and ISM continued around nearby Quiterajo.54Cabo Ligado, ‘Cabo Ligado Update: 30 June–13 July 2025’, ACLED.

Improvised explosive devices (IEDs)

In the course of 2024, ISM began increasingly to rely on improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as a means of warfare.55Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province: Protection Analysis Report’, January 2025. While ISM has largely sought to target military personnel with these munitions, inevitably civilians have also been harmed. This continued to occur in 2025, with an IED injuring a civilian in Quiterajo on 19 May and another injuring several, including children, in Nangade on 23 May.56OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’. In Nambija village in Macomia district, a civilian was killed by an IED in June 2025 – again the device seems to have been placed by ISM.57OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’.

Mozambique is a State Party to the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, which prohibits its forces from using any anti-personnel mine – defined as a munition that is designed or adapted to be activated by a person. This disarmament treaty does not bind ISM directly under international law – and Mozambique is not a party to the UN Convention on Conventional Weapons whose Amended Protocol II of 1996 binds all parties to an armed conflict 58Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons which may be deemed to be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscriminate Effects; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998. – but ISM is subject to the customary IHL principles of distinction and proportionality in attack, underpinned by the duty to take precautions to protect civilians. While not an inherently indiscriminate weapon, the effects of anti-personnel mines, including those of an improvised nature as ISM employ in Cabo Delgado, are all too often indiscriminate.

Mozambique is obligated by the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention to clear and destroy all anti-personnel mines on its territory as soon as possible.59Art 5, Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction; adopted at Oslo, 18 September 1997; entered into force, 1 March 1999.

Aerial bombardment

In August 2024, as noted above, the RSF turned to combat helicopters to bomb ISM forces, an approach that significantly increases the risk of incidental civilian casualties. On 8 August, it was reported that Mucojo was ‘in ashes’ due to the intensity of the RSF’s aerial attacks. This raises concern about compliance with the IHL rules of distinction, proportionality, and precautions in attack. On 16 August 2024, Mucojo was again bombed, with local sources reporting that many civilians had sought refuge in Macomia town.60Cabo Ligado, ‘Cabo Ligado Update: 5–18 August 2024’, ACLED, 22 August 2024.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

Conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence

The armed conflict in the province continues to have very strong elements of sexual and gender-based violence. As Save the Children has reported, the conflict has exacerbated existing levels of rape and other sexual violence and exploitation, with girls as young as 12 years of age abducted, often resulting in sexual violence, early pregnancy, and forced marriage.61Save the Children, ‘Gender and Power Analysis of Child Marriage In Cabo Delgado Province: Understanding the Key Drivers to Propel an Accelerated Action Plan’, Report, June 2024, p 14. Each instance that occurs with sufficient nexus to the conflict is a war crime.

Forced marriages of girls are said to be common in Cabo Delgado.62A. Cascais, ‘Extremists in northern Mozambique use rape as a weapon’, Deutsche Welle, 13 July 2024. ‘Telma’ (not her real name for reasons of protection), a seventeen-year-old girl in Chiúre district, told the organization:

There are girls who have been caught and forced to marry these armed men. Here in the area, there is a girl who escaped after three years and came back last week. Some girls are still in prison today. They are forced to obey everything they are told to do, and they even have children. Even little girls are taken and grow up there, until they become women. Some girls are killed, and the younger ones are left to grow up for a while and then they are forced to have sex.63Save the Children, ‘Gender and Power Analysis of Child Marriage In Cabo Delgado Province: Understanding the Key Drivers to Propel an Accelerated Action Plan’, p 1.

Other women raped and abused by ISM in the past are now speaking about their suffering.64M. Solinas, ‘Les femmes du Cabo Delgado, premières victimes des djihadistes au Mozambique’, Le Monde Afrique, 13 March 2024 (Updated 17 September 2024). Maria was 27 when ISM fighters abducted her and other women from her village and took them to a military camp where they were forced to become ‘wives’. She was subjected to sexual violence and brutal beatings for months until her ISM ‘husband’ grew tired of her and sold her to another fighter for 50 meticais (less than $1). ‘I was later sold a second time to another man’, she said.65H. Caux, ‘Supporting one another, survivors of sexual violence in northern Mozambique begin to heal’, UNHCR, 29 November 2024.

What is more, the problem of sexual and gender-based violence is worsening. The UN reported that the number of people in need of urgent response services increased from more than 475,000 in 2023 to 558,000 in 2024.66Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province, Protection Analysis Update’, January 2025, p 8. Particularly, older women, adolescent girls, and women and girls living with disabilities face heightened risks and challenges in this unstable environment.67Ibid. The early part of 2025 saw a twenty-two per cent rise in Cabo Delgado in reported cases compared to 2024. Part, but not all of this increase is ascribed to improved reporting and a growing awareness of the problem.68OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Cabo Delgado, Nampula & Niassa Humanitarian Snapshot, As of June 2025’. Women and girls face stigmatization and rejection from their communities upon return, as testimonies gathered by UNHCR have demonstrated.69Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province, Protection Analysis Update’, January 2025, p 6.

Moreover, the survivors lack access to quality specialized life-saving services for gender-based violence, such as clinical management of rape, psychosocial support, legal aid, and confidential referral mechanisms. Data show that three quarters of women and girls have no access to specialized, comprehensive services in Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia, and Quissanga, while, according to a 2024 UN assessment, sixty per cent of women and girls feel that the risk of sexual violence has increased in their communities.70Ibid, pp 8, 9.

Accountability for earlier violations remains a serious challenge. Thus, in July 2025, traditional leaders of Palma and 15 surrounding villages, supported by 66 human rights and environmental organizations, formally requested the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to establish an independent investigation into severe human rights violations allegedly committed in 2021 by Mozambican security forces, including members of the Joint Task Force protecting TotalEnergies’ Mozambique LNG project Cabo Delgado. The letter states:

We do not consider that any of the ongoing initiatives are adequate and sufficient to ensure a fully independent and transparent investigation. We strongly believe that an investigation conducted by OHCHR is required to guarantee a fair, impartial, secure and victim-centred process.

Hostage-taking and pillage

Ransom demands for those abducted as hostages, which is a war crime under IHL (as well as more generalized extortion), have been widespread, hindering safe movement for civilians, including aid workers. In June 2025, this concerned especially Macomia, southern Meluco, and Mocímboa da Praia. Along roads such as the N380 and the R766 between Napala and Mucojo, vehicles were stopped at makeshift roadblocks, and passengers were forced to pay to pass. In Ravia (in Meluco), they raided an artisanal mine, demanding 5,000 meticais from each miner before leaving.71OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’.

Similar extortion by ISM occurred at sea, with fishing boats intercepted and released only after ransom. In Pangane, a beach village along the northern coast opposite Mozambique’s largest island national park, the Quirimbas Archipelago, stores were looted and the engines removed from boats whose owners or crew did not make the required payments.72Ibid. In Maculo village, in Mocímboa da Praia, residents were held hostage for two days in May 2025 and forced to pay ‘fees’ for owning boats, canoes, or tents. Fishermen were also under threat from the FADM in their communities. The same month saw reports of arbitrary arrests by the FADM in Ibo, Mocímboa da Praia, and in Quissanga of fishermen the army suspected of having links to ISM.73OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

Child recruitment

ISM continued to recruit and use children as fighters during the reporting period, while also attacking schools, conduct that is generally contrary to IHL.74OCHA, Mozambique: Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2025, December 2024. As part of its activities, in March 2025, ISM conducted preaching during ‘visits’ to village schools in Mocímboa da Praia.75International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Conflict Tracker, March 2025.

About 120 children were abducted in Cabo Delgado in May and June 2025 as part of a ‘surge’ in child recruitment reported by Human Rights Watch. Once taken, they are forced into combat, labour, or early marriage. When ISM fighters ‘enter or attack certain areas, they tend to abduct children’, Augusta Laquite, coordinator at the Association of Women in Legal Careers in Cabo Delgado, told the organization. ‘They take them to train them and later turn them into their own fighters.’ While ISM released some of the children it had abducted earlier in the year, many remained missing, while those who had returned to their communities struggled to reintegrate successfully.76Human Rights Watch, ‘Mozambique: Armed Group’s Child Abductions Surge in North’, News release, Johannesburg, 24 June 2025.

Persons with disabilities in Mozambique

It is not known how many people are living with disabilities in Cabo Delgado, but the number will undoubtedly be high given the extent of violence and the lack of medical and rehabilitative services. Increased use of IEDs will lead to more traumatic amputations of lower limbs. Persons with disabilities in the province, whether their disability resulted from the conflict or predated it, face an especially difficult future. While the UN Global Protection Cluster refers to persons with disabilities in their reports, the references tend to be pro forma without consideration of their specific protection needs.

In its work in Mozambique, Humanity & Inclusion (HI) has focused its actions in Cabo Delgado on helping to promote access to education for children with disabilities with support from the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO). HI provides children with rehabilitation support, including mobility aids such as wheelchairs, to facilitate their access to education.77HI, ‘Mozambique: Actions in process’, undated but accessed 17 August 2025.

- 1‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data project (ACLED), 25 April 2025.

- 2Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘The world’s most neglected displacement crises 2024’, 3 June 2025.

- 3See eg: Lusa, ‘ONG alerta para dificuldades em prestar assistência às vítimas de Moçambique’, Publico, 11 August 2025.

- 4The Soufan Center, ‘Islamic State in Mozambique Rearing Its Head Again’, 15 January 2025.

- 5Ibid.

- 6SAMIM concluded its mission on 15 July 2024. ‘Actor Profile: SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM)’, Cabo Ligado, 2 May 2024; Bofin, ‘ACLED Report: Rwanda in Mozambique: Limits to civilian protection’; ‘Withdrawal of the Southern African Development Community Mission In Mozambique (SAMIM) Force Members from Cabo Delgado’, Southern African Development Community, 5 April 2024; A. Massango, ‘SAMIM formally withdraws from Cabo Delgado’, AIM, 4 July 2024.

- 7See generally: P. Pigou and J. Opperman, ‘Conflict in Cabo Delgado: From the Frying Pan into the Fire?’, Report, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, 15 June 2021; and International Crisis Group, ‘Stemming the Insurrection in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado’, Africa Report No 303, 11 June 2021.

- 8International Organization for Migration (IOM), ‘Mozambique Crisis Response Plan Jan-Dec 2025’, 27 June 2025, p 5.

- 9

- 10‘TotalEnergies plans to restart Mozambique LNG project by August 2025’, Club of Mozambique, 22 May 2025; and C. Howe, ‘WGC TotalEnergies CEO aims to lift force majeure on Mozambique LNG project’, Reuters, 20 May 2025.

- 11‘Actor Profile: Tanzania People’s Defence Force (TPDF)’, Cabo Ligado, 29 May 2024.

- 12‘About EUMAM Moz’, EUMAM Mozambique, 8 January 2025.

- 13https://acleddata.com/monitor/mozambique-conflict-monitor-cabo-ligado

- 14C. Haenlein, J. de Deus Pereira, M. Jones and L. O’Shea, ‘Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Mozambique A Bottom-Up Analysis of Local Perceptions’, Whitehall Report 1-25, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), London, June 2025, p 28.

- 15C. Marin, ‘Resources and conflict in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado’, Le Monde diplomatique, 5 July 2025.

- 16LUSA, ‘Mozambique: Cabo Delgado businesses fear being left out of TotalEnergies’ project’, Club of Mozambique, 4 August 2025.

- 17International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Database, March 2025.

- 18International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Database, May 2025.

- 19‘Briefing: IS claims spate of deadly attacks on troops, civilians in Mozambique’, BBC Monitoring, 11 November 2024.

- 20The Soufan Center, ‘Islamic State in Mozambique Rearing Its Head Again’.

- 21UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’, 10 July 2025.

- 22Security Council Report, ‘Counter-Terrorism, January 2025 Monthly Forecast’, 30 December 2024.

- 23Haenlein et al, ‘Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Mozambique A Bottom-Up Analysis of Local Perceptions’, p 27.

- 24

- 25Cabo Ligado, ‘Cabo Ligado Update: 22 July–4 August 2024’, ACLED, 8 August 2024.

- 26

- 27OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’, 10 July 2025.

- 28OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’, 12 June 2025.

- 29International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’.

- 30OCHA, ‘Mozambique 2025 Humanitarian Response – Drought Appeal, as of 31 May 2025’, 2 July 2025.

- 31

- 32ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37MSF, ‘As Cabo Delgado experiences an alarming rise in violence, access to healthcare for communities in vulnerable circumstances is being severely compromised’, Press release, Pemba, 16 July 2025.

- 38Ibid.

- 39Ibid.

- 40ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28. See also Art 11, Additional Protocol II of 1977.

- 41OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

- 42International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Database, April 2025.

- 43‘IS-Mozambique Launches Wave of High-Profile Attacks’, Africa Defense Forum, 17 June 2025, quoting Fernando Lima, a researcher with ACLED’s Cabo Ligado conflict observatory.

- 44N. Mendes, ‘Insurgents Attack Russian Vessel off Mocímboa da Praia’, The Mozambique Times, 13 May 2025.

- 45Ibid.

- 46.Global Protection Cluster, ‘Mozambique Protection Analysis Update’, 27 February 2025.

- 47Human Rights Watch, ‘Mozambique’, World Report 2025.

- 48OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

- 49Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province, Protection Analysis Update’, January 2025, p 2.

- 50Ibid, p 3.

- 51OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’.

- 52International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Conflict Tracker, June 2025.

- 53‘Mozambican navy accused of killing fishermen off coastal‘ Macomia, Zitamar News, 7 July 2025.

- 54Cabo Ligado, ‘Cabo Ligado Update: 30 June–13 July 2025’, ACLED.

- 55Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province: Protection Analysis Report’, January 2025.

- 56OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

- 57OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’.

- 58Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons which may be deemed to be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscriminate Effects; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998.

- 59Art 5, Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction; adopted at Oslo, 18 September 1997; entered into force, 1 March 1999.

- 60Cabo Ligado, ‘Cabo Ligado Update: 5–18 August 2024’, ACLED, 22 August 2024.

- 61Save the Children, ‘Gender and Power Analysis of Child Marriage In Cabo Delgado Province: Understanding the Key Drivers to Propel an Accelerated Action Plan’, Report, June 2024, p 14.

- 62A. Cascais, ‘Extremists in northern Mozambique use rape as a weapon’, Deutsche Welle, 13 July 2024.

- 63Save the Children, ‘Gender and Power Analysis of Child Marriage In Cabo Delgado Province: Understanding the Key Drivers to Propel an Accelerated Action Plan’, p 1.

- 64M. Solinas, ‘Les femmes du Cabo Delgado, premières victimes des djihadistes au Mozambique’, Le Monde Afrique, 13 March 2024 (Updated 17 September 2024).

- 65H. Caux, ‘Supporting one another, survivors of sexual violence in northern Mozambique begin to heal’, UNHCR, 29 November 2024.

- 66Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province, Protection Analysis Update’, January 2025, p 8.

- 67Ibid.

- 68OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Cabo Delgado, Nampula & Niassa Humanitarian Snapshot, As of June 2025’.

- 69Global Protection Cluster, ‘Republic of Mozambique, Cabo Delgado Province, Protection Analysis Update’, January 2025, p 6.

- 70Ibid, pp 8, 9.

- 71OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 30 June 2025’.

- 72Ibid.

- 73OCHA, ‘Mozambique: Access Snapshot – Cabo Delgado Province, as of 31 May 2025’.

- 74OCHA, Mozambique: Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2025, December 2024.

- 75International Crisis Group, CrisisWatch Conflict Tracker, March 2025.

- 76Human Rights Watch, ‘Mozambique: Armed Group’s Child Abductions Surge in North’, News release, Johannesburg, 24 June 2025.

- 77HI, ‘Mozambique: Actions in process’, undated but accessed 17 August 2025.