Conflict Overview

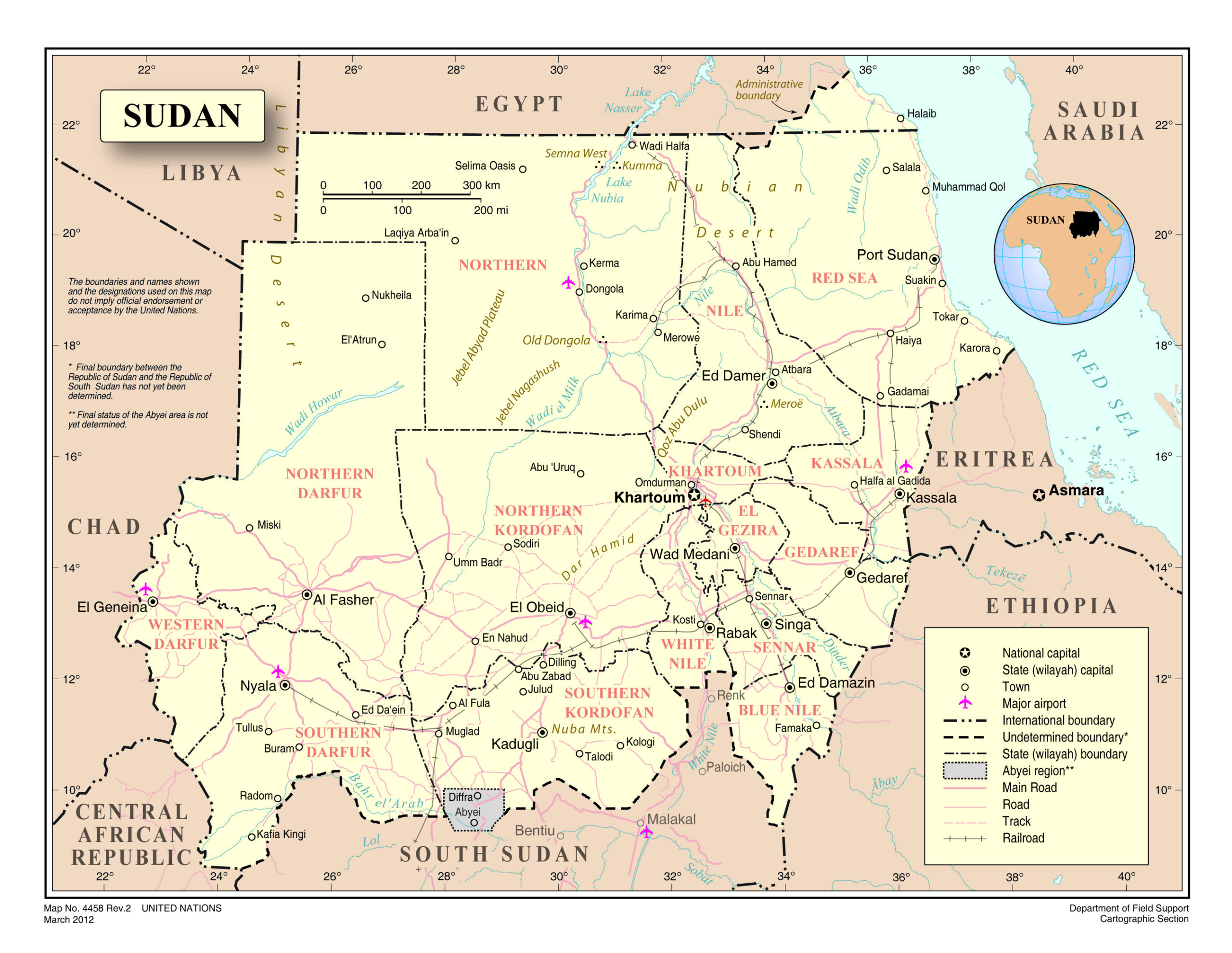

Since independence in 1956, Sudan has been marked by multiple armed conflicts with frequent and serious violations of international humanitarian law (IHL).1M. Öhm, ‘Sudan’, Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 12 November 2024; ‘Findings of the investigations conducted by the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission for the Sudan’, UN Doc A/HRC/57/CRP.6, 23 October 2024 (IIFFM October 2024 report), para 116; Center for Preventive Action, ‘Civil War in Sudan’, Council of Foreign Relations, 15 April 2025. The conflict that erupted in Darfur in 2003 set State armed forces and Janjaweed militia against rebel groups, notably the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army and the Justice and Equality Movement, and was characterized by severe abuses against civilians.2IIFFM October 2024 report, paras 92, 116, and 121. The United Nations (UN) Commission of Inquiry concluded in 2005 that there was ‘no doubt that some of the objective elements of genocide materialized in Darfur’, while rejecting the existence of a State policy of genocide.3‘Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary-General’, Geneva, 25 January 2005, paras 507, 518. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-North (SPLM-N), which split into two factions in 2017, has, for more than a decade, been fighting the Khartoum government in both Kordofan and Blue Nile state.4K. A. Hassan, ‘Spilling Over: Conflict Dynamics in and around Sudan’s Blue Nile State. 2015–19’, Small Arms Survey, March 2020.

After President Omar al-Bashir was deposed by the military in April 2019, a transitional government took power,5Center for Preventive Action, ‘Civil War in Sudan’; M. Taha, P. Knopf, and A. Verjee, ‘Sudan, One Year After Bashir’, United States Institute of Peace, 1 May 2020. but divisions between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – a paramilitary body of former Janjaweed fighters – over the integration of the RSF into the army6A. M. Ali and E. Kazemi, ‘Sudan Situation Update: April 2023: Political Process to Form a Transitional Civilian Government and Shifting Disorder Trends’, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED), 14 April 2023; UN Department for General Assembly and Conference Management, ‘Janjaweed militias’; Center for Preventive Action, ‘Civil War in Sudan’, Council of Foreign Relations, 15 April 2025. triggered hostilities in Khartoum on 15 April 2023 that quickly spread, especially to Darfur and Kordofan.7‘Fighting in Sudan: A timeline of key events’, Al Jazeera, 31 May 2024; ‘At least 40 killed in air strike on Khartoum market, volunteers say’, Reuters, 10 September 2023; ‘UNITAMS Statement on the Killing of the Governor of West Darfur’, United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan, 15 June 2023; G. Joselow and M. Fiorentino, ‘Fire used as “weapon of war” in Sudan as entire towns and villages burned to the ground’, NBC News, 16 June 2024; Center for Preventive Action, ‘Civil War in Sudan’. The resulting non-international armed conflict between the SAF and the RSF has been intense, with widespread and serious IHL violations by both.8Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Events of 2024’, World Report 2025; US Department of State, ‘2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Sudan’; Center for Preventive Action, ‘Civil War in Sudan’. Officially, the Darfur Joint Protection Force remained neutral, but many within it abandoned neutrality to fight with the SAF.

The fact that the RSF is composed of former Janjaweed fighters who played a major role in the crimes against civilians in Darfur in 2003 continues to fuel tensions between Darfuri communities and the RSF.9K. Ferguson, ‘The RSF are out to finish the genocide in Darfur they began as the Janjaweed. We cannot stand by’, The Guardian, 24 July 2023; M. Nashed, ‘“Can’t trust the Janjaweed”: Sudan’s capital ravaged by RSF rule’, Al Jazeera, 20 January 2024. The acts of the RSF in the aftermath of its capture of El Fasher in late October 2025 once again raised the spectre of genocide in Sudan. Foreign involvement in the conflict has involved allegations of supply of arms to the RSF by the United Arab Emirates (UAE).10P. Zengerle, ‘US lawmakers find UAE provides weapons to Sudan RSF; UAE denies this’, Reuters, 24 January 2025; C. van Hollen, ‘Van Hollen, Jacobs Confirm UAE Providing Weapons to RSF in Sudan, in Contradiction to its Assurances to US’, 24 January 2025. A case brought by Sudan against the UAE before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) alleging complicity in genocide did not proceed to a judgment on the merits as the ICJ held it did not have jurisdiction.11ICJ, Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in Sudan (Sudan v United Arab Emirates), Order, 5 May 2025. with additional support coming from a residual Wagner Group presence,12N. Elbagir et al, ‘Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia’s Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan’s army’, CNN, 21 April 2023. Chad,13‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 74. and an – acknowledged – presence of Colombian private military contractors.14Ibid, para 15. In turn, the SAF is said to have received support from Ukrainian special forces.15I. Lovett et al, ‘Ukraine Is Now Fighting Russia in Sudan’, The Wall Street Journal, 6 March 2024; K. Zakharchencko and C. York, ‘Ukrainian Drones “Destroy Russian Mercenaries” in Sudan’, Kyiv Post, 30 January 2024; D. Kirichencko, ‘How Ukraine Is Challenging Russia in Africa and the Middle East’, Lawfare, 2 July 2025.

Key Events since 1 July 2024

During the reporting period, the SAF retook several RSF-held areas,16M. Nashed, ‘War in Sudan: Humanitarian, fighting, control developments, August 2025’, Al Jazeera, 31 August 2025. including the main cities in Sennar, Al Gezira, and Khartoum states17A. M. Ali, J. G. Birru and N. Eltayeb, ‘Two years of war in Sudan: How the SAF is gaining the upper hand’, ACLED, 15 April 2025. and in May 2025, Khartoum.18‘Sudan’s army declares Khartoum state “completely free” of paramilitary RSF’, Al Jazeera, 20 May 2025; C. Macaulay, ‘Sudan rebels entirely pushed out of Khartoum state, army says’, BBC, 20 May 2025. Despite significant territorial losses, the RSF continues to hold substantial territory, including most of Darfur and much of Kordofan.19N. Booty and F. Chothia, ‘Sudan war: A simple guide to what is happening’, BBC, 4 July 2025; Nashed, ‘War in Sudan: Humanitarian, fighting, control developments, August 2025’. El Fasher was the sole locality in Darfur where the SAF had maintained a ground presence alongside the Darfur Joint Protection Force (DJPF).20‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, 17 April 2025, para 6. See also A. Gouja, ‘Inside the battle for El Fasher: “Innocent lives are lost every day”’, The New Humanitarian, 27 November 2024; Nashed, ‘War in Sudan: Humanitarian, fighting, control developments, August 2025’. In May 2025, the RSF for the first time attacked Port Sudan, the humanitarian hub previously considered relatively safe.21B. P. Usher, ‘Drone attacks raise stakes in new phase of Sudan’s civil war’, BBC, 15 May 2025. This followed the signing by the RSF and its allies in February of a charter on forming a parallel government,22‘Surprise rebel alliance could boost Sudan’s beleaguered RSF’, New Indian Express, 24 February 2025. claiming it would ‘represent all of Sudan’.23M. Nashed, ‘Sudan’s competing authorities are beholden to militia leaders, say analysts’, Al Jazeera, 23 July 2025.

The Fall of El-Fasher

In November 2025, El Fasher fell to the RSF after an eighteen-month siege. The aftermath involved massacres of unarmed civilians, including hundreds of patients in a hospital. Videos and witness accounts show trenches filled with bodies, and RSF fighters hunting down civilians as they tried to flee. Blood pools in several locations around the city could be seen from satellites.24A. Mohdin, ‘Sudan’s latest massacre has been exposed from satellite images – how much longer can the world look away?’, The Guardian, 31 October 2025. At an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council, Tom Fletcher, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, criticized Member States for letting the crisis reach this point. ‘I have found the limits of my ability and the UN’s authority’, he said, calling on States to ‘stop arming’ the RSF, but without naming the responsible party.25D. Walsh, S. Varghese, and P. Baskar, ‘Executions and Mass Casualties: Videos Show Horror Unfolding in Sudan’, The New York Times, 30 October 2025.

The crimes continued in the days that followed in and around El Fasher. Women and girls who escaped the city described brutal sexual violence by RSF fighters. Five survivors told howthey were gang-raped by RSF and affiliated fighters. Some of the abuse lasted for hours or even days, and sometimes occurred in the presence of family members they were fleeing with. ‘RSF soldiers took turns on us’, said a twenty-year-old woman and mother of four who was kept captive for two days by fighters. ‘Each time, a group would arrive in military vehicles, take us to a room, and rape us violently before leaving.’ The woman said she was with a group of twelve other women and girls who were also gang-raped, and that she was threatened with being shot.26A. Gouja, ‘Women and girls fleeing El Fasher describe widespread RSF sexual violence’, The New Humanitarian, 21 November 2025.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

In the reporting period, three non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) were ongoing in Sudan. Two involved the SAF fighting a non-State armed group:

- Sudan (supported by the Darfur Joint Protection Force, DJPF) v RSF

- Sudan v SPLM-North (al-Hilu faction).

The third NIAC is between two organized armed groups:

- RSF v SPLM-North (al-Hilu faction).

Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and other rules of customary IHL apply to all three NIACs. Sudan is also a State Party to Additional Protocol II of 197727.Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts; adopted at Geneva, 8 June 1977; entered into force, 7 December 1978. The two pre-existing Additional Protocol II-type NIACs to which Sudan is a party, fighting against the RSF and the SPLM-North (al-Hilu faction), respectively, continue to meet the additional requirements of Article 1(1) of Additional Protocol II – notably, that the group in question exercised a level of territorial control that would enable it to sustain military operations and implement the Protocol – and this treaty is applicable. The Protocol does not, however, apply to the NIAC between the RSF and the SPLM-North (al-Hilu faction) as Article 1(1) limits the Protocol’s jurisdiction to armed conflict between the State and an organized armed group.28A. Bellal and S. Casey-Maslen, The Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions in Context, Oxford University Press, 2022, para 1.44.

Sudan is not a State Party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court,29Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court; adopted at Rome, 17 July 1998; entered into force, 1 July 2002 (ICC Statute). but the situation in Darfur was referred to the Court in 2005 by the UN Security Council30UN Security Council Resolution 1593, adopted on 31 March 2005 eleven votes to nil with four abstentions (Algeria, Brazil, China, and the United States), operative para 1. and the Court continues to have jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide perpetrated in that region.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

During the reporting period, serious violations of IHL continued to be committed on a massive scale.31‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 5. In particular, the SAF and RSF indiscriminately attacked civilians and civilian objects, wantonly killing and injuring in bombings and causing extensive damage to infrastructure.32Amnesty International, ‘The State of the World’s Human Rights’, April 2025, p 346; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities – Report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission for the Sudan’, UN Doc A/HRC/60/22, 5 September 2025, paras 23, 33, and 40 Civilians have been murdered, tortured, raped, forcibly displaced, starved, arbitrarily detained, and subjected to enforced disappearance and forced recruitment.33‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 23. As many as 150,000 people have reportedly been killed,34Center for Preventive Action, ‘Civil War in Sudan’. and more than 14.2 million people have been uprooted from their homes.35International Organization for Migration (IOM), ‘DTM Sudan Mobility Update (19)’, 8 July 2025.

The RSF has sought to instil fear and consolidate control while the SAF has relied heavily on the DJPF and allied militias, as well as on indiscriminate airstrikes against RSF-held or disputed areas.36‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 6–7. Many violations targeted communities based on ethnicity and/or were committed as reprisals for alleged allegiance,37Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 24. particularly amid shifts in territorial control, with internally displaced persons (IDPs) particularly exposed to abuses.

Despite multilateral efforts to protect the civilian population – including the Jeddah Declaration of Commitment to Protect the Civilians of Sudan signed by the SAF and the RSF on 11 May 202338Jeddah Declaration of Commitment to Protect the Civilians of Sudan. and the UN-mediated negotiations launched on 11 July 2024 to secure a ceasefire and facilitate humanitarian relief39‘Sudan: UN-hosted talks on aid relief and civilian protection to continue in Geneva’, UN News, 12 July 2024. – the situation after two years of fighting was described by the United Nations as the ‘world’s worst humanitarian crisis’.40UN, ‘Sudan, after two years of war‘, Spotlight on Sudan, 14–15 April 2025. In the words of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC): ‘More than a forgotten crisis, Sudan is becoming an ignored crisis … and the humanitarian crisis in Sudan is first and foremost stemming from the disrespect of the laws of war’.41ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, April 2025, p 3.

The scale of atrocities had already prompted the International Criminal Court to open a new investigation in July 2023,42ICC ‘Fortieth report of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court to the UN Security Council pursuant to Resolution 1593 (2005)’, 27 January 2025, p 6. and led the United States (US) – among others – to sanction the leaders of both the SAF and the RSF.43US Department of State, ‘Genocide Determination in Sudan and Imposing Accountability Measures’, 7 January 2025; US Department of the Treasury, ‘Treasury Sanctions Leader of Sudanese Armed Forces and Weapons Supplier’, Press release, 16 January 2025; US Department of State, ‘Imposing Measures on Sudan for its Use of Chemical Weapons’, Press statement, 22 May 2025. In early November 2025, the Court’s Office of the Prosecutor expressed its ‘profound alarm and deepest concern’ over the reports emerging from El-Fasher about crimes allegedly committed by the RSF. Such acts, if substantiated, ‘may constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute.’ The Office further recalled that it has jurisdiction over crimes committed in the ongoing conflict in Darfur.44Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC, ‘Statement of the ICC Office of the Prosecutor on the situation in El-Fasher, North Darfur’, 3 November 2025.

Civilian Objects under Attack

During the period under review, many attacks by the SAF and RSF indiscriminately hit areas controlled by the enemy, striking homes, schools, mosques, markets, water points, power-generating plants, and medical facilities.45‘Sudan Media Forum: Hunger, shelling, airstrikes scourge Sudan’s civilians’, Radio Dabanga, 24 August 2024; ‘Shells fall on crowded markets in Darfur’, Radio Dabanga, 27 August 2024; ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 34 and 55; ‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 191; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 71, 73, and 79. Airstrikes and artillery strikes by both parties hit densely populated areas, including camps for the displaced as well as towns and villages.46‘Sudan Media Forum: Hunger, shelling, airstrikes scourge Sudan’s civilians’; Amnesty International, ‘The State of the World’s Human Rights’, April 2025, p 346; UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS), ‘Sudan’, May 2025; Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, IHL in Focus: Weaponizing Water and Humanitarian Collapse in Sudan, An International Humanitarian Law Assessment, 4 August 2025 (hereafter, Geneva Academy 2025 Spot Report on Sudan), p 8; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 23. In some instances, attacks were targeted on ethnic grounds. Pillage of civilian property was regularly reported.

There were serious violations of the principle of distinction,47ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants’; ICRC, ‘Customary IHL Rule 7: The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. including the prohibition of indiscriminate attacks,48ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’. the principle of proportionality in attack,49ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’. and the underlying rule of precautions in attack.50ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’. Also regularly violated were rules specially protecting medical facilities51ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28: ‘Medical Units’. and objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population,52ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 54: ‘Attacks against Objects Indispensable to the Survival of the Civilian Population’. as well as the prohibition of pillage.53ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 52: ‘Pillage’ Some of the bombardment of towns and villages was sufficiently widespread and systematic to amount to violence intended to spread terror among the civilian population54ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 2: ‘Violence Aimed at Spreading Terror among the Civilian Population’. – a serious violation of IHL – and crimes against humanity under international criminal law.55See Art 7, ICC Statute.

Attacks against towns, villages, and IDP camps

After a period of relative calm following a ceasefire that held from April 2023 to January 2024 and divided the city between the SAF, the RSF, and the DJPF, in 2024, El Fasher emerged as the epicentre of the conflict in Darfur. As the only major locality in the region still with an SAF presence, it became a key battleground for territorial control with the RSF and their allies, who indiscriminately attacked densely populated areas.56‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 16–19, 22, and 31.

Neighbourhoods under the control of the SAF in El Fasher, mainly inhabited by non-Arab-communities, as well as nearby villages and towns were repeatedly attacked and shelled by the RSF.57Ibid, paras 22–24 and 29; Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 73. Some, such as al-Wahda and al-Thawra, were destroyed or burned down after intensive shelling in late 2024, or in the case of the village of Borush and Shagra town, in early 2025.58‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 73. See also: ‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, 21 October 2024, para 9. The SAF shelled and bombed neighbourhoods controlled by the RSF, notably in the east of El Fasher. After the violence prompted civilians to flee, the RSF started to occupy homes and schools leading the SAF to bomb entire residential areas.59‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 80. See also ‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, para 9; ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 19 and 22–23.

Camps for IDPs surrounding El Fasher (Abu Shouk, Shagra, and Zamzam) have been repeatedly attacked by the RSF, causing the further displacement of many of their residents.60‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 25. Since mid-July 2024, the RSF has heavily shelled Abu Shouk, north of El Fasher, with artillery strikes occurring almost daily in 2025.61Ibid, para 26. The shelling destroyed thousands of homes and damaged water sources as well as medical facilities.62‘At least six killed, 20 wounded in shelling of Sudan’s El Fasher camp’, Sudan Tribune, 6 May 2025.The Zamzam camp to the south of the city was also increasingly shelled by the RSF from May 2024 and attacks intensified when the DJPF moved towards the camp in late November 2024.63‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 24. Between 11 and 13 April 2025, the RSF launched a large-scale ground offensive on the camp, destroying shelter, markets, and healthcare facilities, and burning parts of the camp, which has been under its control since then.64‘Sudan’s RSF claims control of major Darfur camp, civilians flee’, Reuters, 14 April 2025; ‘At least six killed, 20 wounded in shelling of Sudan’s El Fasher camp’, Sudan Tribune, 6 May 2025; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 28. The RSF said the camp was being used for military purposes, a claim denied by humanitarian actors, which noted that the fighting took place fifteen kilometres away.65‘Sudan’s RSF claims control of major Darfur camp, civilians flee’, Reuters, 14 April 2025; E. Husham, ‘“A tree is worth more”: Sudanese civilians fleeing RSF attacks on Zamzam’, Al Jazeera, 27 April 2025.

Other cities and villages across Sudan were also extensively targeted by both parties. Following the capture of an RSF base by the SAF in Bir Maza in early October 2024, the RSF and allies attacked several villages and towns between Kutum town and Anka (in Kutum locality) that they perceived as supporting the SAF. In the course of these attacks, towns and villages were burnt and looted, causing massive displacement.66‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 34. After RSF commander Abu Aqla Keikel and his forces defected to the SAF on 20 October 2024, the RSF attacked and looted 30 towns and villages in his stronghold east of Al Gezira, reportedly killings hundreds, committing widespread sexual violence, and displacing more than 100,000 people.67Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Rapid Support Forces Target Civilians’, 10 November 2024; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 35.

In a similar vein, after recapturing Al Gezira in January 2025, the SAF and their allies launched retaliatory attacks against Kanabi villages, accusing the Kanabi community of siding with the RSF. Homes were burnt, and property and livestock looted.68‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 36. On 10 January 2025, the Sudan Shield Forces, an armed group fighting alongside the SAF, attacked the village of Tayba in Al Gezira, killing at least twenty-six people, including one child, and injuring many more. The attackers systematically looted property, including food supplies, and set fire to houses.69Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Armed Group Allied to the Military Attacks Village’, 25 February 2025. After the launch of a massive offensive to recapture Khartoum by the SAF in September 2024, warring parties were described by the UN Secretary-General as having ‘shown little to no regard for civilian lives and property in their attempt to control the capital’.70‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, para 8.

The SAF often bombed areas controlled by the RSF.71‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 6 and 54; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 73. See also: ‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, para 9. For instance, on 4 August 2024, the SAF conducted two airstrikes in Zamzam displacement camp, damaging at least sixteen homes and injuring an unknown number of civilians, including children.72‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 55. Between November 2024 and February 2025, the SAF dropped powerful unguided bombs on residential and commercial neighbourhoods in Nyala in South Darfur, a city of more than 800,000 inhabitants that had fallen under RSF control in late October 2023. Scores of civilians, including women and children, died as a result. Human Rights Watch reported that the SAF carried out five airstrikes on 3 February 2025 using (among others) unguided high-explosive munitions. At least thirty-two civilians were killed and dozens more were injured. A strike on a peanut-oil factory on 4 February 2025 killed at least twenty-five and injured twenty-one.73Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Armed Forces Airstrikes in South Darfur: Indiscriminate Strikes Add to Record of War Crimes’, 4 June 2024.

These consistent violations of the principle of distinction, some amounting to attacks directed against the civilian population and civilian objects and others indiscriminate in nature, are likely to amount to war crimes in many instances, including of terror attacks.

Attacks against medical facilities

Sudan’s health system has been devastated by the ongoing conflicts.74A. Elamin et al, ‘Sudan: from a forgotten war to an abandoned healthcare system’, BMJ Global Health, Vol 9, No 10 (30 October 2024); ICRC, ‘Sudan faces health crisis as conflict devastates medical infrastructure’, News release, 8 August 2024 The scale of destruction and damage to medical infrastructure, often intentional, by both the SAF and the RSF, coupled with the targeting of medical personnel (see below),75‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 98. have driven the healthcare system in Sudan to near collapse.76Ibid, para 88. Since the outbreak of the conflict, many hundreds of attacks on health facilities have been recorded and fewer than one in four facilities in affected areas remain operational.77UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Sudan: Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan – Executive Summary’, Humanitarian Programme Cycle 2025, December 2024, p 9; ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 4. Darfur has been especially impacted. About half of the reported attacks took place during the siege of El Fasher and, by March 2025, more than 200 medical facilities were no longer operational in the city.78OCHA, ‘Today’s top news: Occupied Palestinian Territory, Syria, Sudan, Mozambique’, 11 March 2025; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 89. At the same time, the health facilities still functioning faced severe shortages of medical equipment, medicine, and staff.79ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 4. As a result, two in three Sudanese civilians no longer have access to basic health services,80ICRC, ‘Sudan faces health crisis as conflict devastates medical infrastructure’, ICRC News Release, 8 August 2024; ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 4. while more than 20 million required medical attention for injury, malnutrition, or disease.81‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 89.

The RSF conducted widespread and systematic attacks against healthcare facilities across Sudan, including Al Gezira, Khartoum, and North Darfur, attacking hospitals and medical centres, killing or harassing medical personnel and patients, and looting medical supplies.82ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, April 2025, p 4; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 90. In particular, attacks on facilities in and around El Fasher, including those in the surrounding displacement camps, intensified from May 2024 onwards.83‘Shells fall on crowded markets in Darfur’, Radio Dabanga, 27 August 2024; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 91–96. By April 2025, only one healthcare facility inside El Fasher remained partly operational and all medical facilities had been destroyed in Abu Shouk camp. In addition, the transfer of patients forced by the closure of medical facilities became more dangerous, as relatives attempting to evacuate patients were sometimes shot and the RSF tightened their control of the roads.84Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 33; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 91–96.

Despite their denials,85‘Response from the Rapid Support Forces to Human Rights Watch’, 22 July 2024, Annex II to Human Rights Watch, ‘“Khartoum is not Safe for Women!” Sexual Violence against Women and Girls in Sudan’s Capital’, 28 July 2024. the RSF has repeatedly shelled and raided several hospitals in Khartoum since the beginning of the conflict.86Human Rights Watch, ‘“Khartoum is not Safe for Women!”; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 97. They attacked and looted Al-Hilaliya hospital in Al Gezira in late November 2024, threatening to kill medical staff as they did so.87‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 97. In January 2025, a drone strike on Al Saudi Hospital – the last functioning civilian hospital in El Fasher – killed around 70 people, including patients, and left the facility severely damaged. Although it was not certain whether the SAF or the RSF had conducted the attack, residents blamed the RSF for the attack.88‘Dozens killed in drone attack on hospital in Sudan’s Darfur’, Al Jazeera, 25 January 2025; ‘Scores killed in hospital attack in Sudan’s besieged El Fasher, says WHO’, The Guardian, 26 January 2025; ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 4.

Attacks on medical facilities or their surroundings were also launched by the SAF, notably in Khartoum, northern Darfur (including El Fasher), and West Kordofan.89‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 33; Human Rights Watch, ‘“Khartoum is not Safe for Women!”’; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 99 and 101. Since late August 2024, the SAF’s bombing campaign intensified across much of Darfur and central Sudan. Medical facilities, along with other civilian objects, have been struck, with the SAF claiming that military presence at those sites warranted the strikes.90‘Sudan Media Forum: Hunger, shelling, airstrikes scourge Sudan’s civilians’. In particular, the SAF mounted several airstrikes on Ed Daein (East Darfur) on 20 August 2024, targeting the teaching hospital and the kidney dialysis centre (which only reopened nine months later),91‘El Daein Dialysis Center Resumes Operations’, Darfur 24, 19 March 2025. in addition to the city’s Grand Market next to the Grand Mosque and El Khansaa Elementary School for Girls.92‘Battles continue in Sudan, air raids on East Darfur hospital kill four’, Radio Dabanga, 21 August 2024; ‘Sudan Media Forum: Hunger, shelling, airstrikes scourge Sudan’s civilians’. Reports indicate that the strike killed a dozen civilians and left many others wounded.93Metis, ‘Aire Delivered event in Sudan on Tue 20th August 2024’, Fenix Insight, 20 August 2024; ‘Shells fall on crowded markets in Darfur’, Radio Dabanga, 27 August 2024; Insecurity Insight, ‘Attacks on Health Care in Sudan: 07-20 August 2024’, August 2024.

It is unclear whether the victims were exclusively patients. Notably, however, no RSF personnel were reportedly killed or injured, gainsaying an alleged military presence. Under IHL, medical units must be respected and protected by the parties to the conflict.94ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28: ‘Medical units’; Art 11, Additional Protocol II. Their special protection may be temporarily lost if they are used to commit ‘acts harmful to the enemy’ outside their humanitarian duties, after due warning and a time limit have been given and remained unheeded.95ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 25: ‘Medical Personnel’; Rule 28: ‘Medical Units’, and Rule 29: ‘Medical Transports’; Art 11(2), Additional Protocol II. In such a case, the rule of proportionality in attack still applies.

Attacks against humanitarian aid

Humanitarian facilities have been also targeted and/or affected in crossfire during the reporting period,96‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 105. violating the rules on the protection against attack of civilian objects. On 19 December 2024, the World Food Programme (WFP) Field Office Compound in Yabus (Blue Nile) was bombed from the air; three staff were killed in the attack.97Ibid, para 106. Although the area was reported to be under the control of the SPLM-North Al-Hilu faction, the Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while condemning the attack, said the SAF were not conducting any military operations in the area at the time.98‘World Food Programme says three staff killed in Sudan by aerial strike’, Reuters, 20 December 2024; ‘WFP staff killed in Sudan airstrike, UN demands investigation’, Sudan Tribune, 21 December 2024. Despite the UN’s call for an investigation,99‘Outraged by Killing of Three World Food Programme Staff Members in Sudan, Secretary-General Calls for Thorough Investigation’, Press release, 20 December 2024. the perpetrator has not been identified. Although the RSF possess drones, including long-range aircraft, the SAF are the only party with manned combat aircraft.100Z. M. Salih, ‘Conflict in Sudan: A Map of Regional and International Actors’, Wilson Center, 19 December 2024; N. Eltahir, ‘Exclusive: Long-range ‘kamikaze’ drones seen near RSF base could worsen conflict in Sudan’, Reuters, 12 September 2025.

On 29 May 2025, the RSF shelled a WFP facility in El Fasher, damaging a workshop, an office building and a clinic.101‘WFP-UNICEF: 5 die in raid on aid convoy in North Darfur’, Radio Dabanga, 3 June 2025; ‘Security Council Press Statement on Sudan’, 12 June 2025. On 2 June, a drone strike hit a joint WFP and UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) humanitarian convoy. The attack killed five humanitarian workers and injured several others, also damaging several trucks with food supplies destined for El Fasher. The parties to the conflict had been informed of the convoy’s route, and the fifteen trucks had WFP and UNICEF markings. The convoy was struck after the RSF reportedly halted it near El Koma while authorization to proceed to El Fasher was pending.102‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 109; ‘WFP/UNICEF humanitarian aid convoy carrying life-saving supplies attacked in Sudan’s North Darfur’, Joint Statement, 3 June 2025. The UN also called for an urgent investigation and for accountability.103‘Security Council Press Statement on Sudan’, 12 June 2025. While none of WFP, UNICEF, and the UN attributed responsibility, the RSF controlled El Koma and most of northern Darfur at the time of the attack.104‘WFP-UNICEF: 5 die in raid on aid convoy in North Darfur’.

Attacks against water and electricity infrastructure

During the reporting period, other critical infrastructure, notably supporting water and the generation of electricity, was targeted or heavily damaged in the course of fighting between the RSF and the SAF.105Geneva Academy 2025 Spot Report on Sudan, pp 7–8; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 77. Whereas the RSF relied predominantly on artillery shelling until early 2025 before resorting also to drone strikes, the SAF frequently bombarded sites from the air.106Geneva Academy 2025 Spot Report on Sudan, p 8.

The RSF in particular systematically attacked water infrastructure, particularly in areas predominantly inhabited by non-Arab ethnic groups107Ibid, p 6. and around El Fasher.108‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 77. For instance, after briefly seizing Golo water reservoir and cutting off its supply of water to El Fasher (its primary water source) and the nearby IDP camps – in February 2025, the RSF damaged water systems in Shagra, aggravating the existing water shortages in the city.109Geneva Academy 2025 Spot Report on Sudan, p 7; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 77. A water truck supplying Saudi hospital in El Fasher was destroyed by artillery fire in May, depriving 1,000 patients of water.110OCHA, ‘Today’s Top News: Occupied Palestinian Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Haiti’, 15 May 2025. On multiple occasions, the SAF attacked wells in nearby Mellit once they fell under RSF control.111‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 82.

On several occasions, electricity infrastructure across Sudan was hit by drone strikes attributed to the RSF. This includes an attack in early April 2025 on Merowe dam, which supplies up to forty per cent of Sudan’s electricity. The following month, several power stations in Omdurman were hit, further disrupting electricity supply and causing large-scale blackouts.112Geneva Academy 2025 Spot Report on Sudan, p 8; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 76. See also: ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 7. The RSF also frequently targeted El Fasher’s grid, interrupting electricity and internet services for prolonged periods of time.113‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 76. The blackouts disrupted water systems as well as hospitals and other vital services.114ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 7; Geneva Academy 2025 Spot Report on Sudan, p 8. In April 2025, fuel shortages in El Fasher and the surrounding camps affected the functioning of wells, meaning it took up to forty-eight hours to fill a single jerrycan in Zamzam camp.115‘Hundreds killed in Sudan’s camps for displaced people’, UN News, 24 April 2025; OCHA, ‘Sudan: Humanitarian Access Snapshot: Al Fasher and Zamzam (as of 8 April 2025)’, 10 April 2025; SAPA, ‘SUDAN: North Darfur Situation Update’, 15 April 2025. Attacks on essential infrastructure and resulting water supply breakdowns have sparked a cholera epidemic across Sudan: since the outbreak in July 2024, 83,000 cases and 2,100 deaths have been reported.116ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 7; OCHA, ‘Sudan: Cholera Operational Update (3 July 2025)’, 3 July 2025.

Civilians under Attack

A persistent feature of the Sudan conflicts, particularly the NIAC betweent the SAF and the RSF, has been the ‘continued, coordinated large-scale attacks on civilians’. From July 2024 to April 2025, more than 400 incidents were recorded in which parties to the conflict killed and injured a total of 5,000 civilians through a combination of artillery airstrikes, and drone attacks.117International NGO Safety Organisation, ‘Two years of conflict in Sudan, marked by continued attacks on civilians and aid workers’, 15 April 2025.

Civilians were often targeted based on their ethnicity or because of their real or perceived affiliation with the enemy.118‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, para 10; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 31, 33, and 40. The violations concern not only war crimes but, given the widespread and systematic nature of the attacks on civilians, also crimes against humanity. The Fact-Finding Mission found, with respect to the RSF, that these crimes include extermination.119‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 87 and 104. In Kutum locality, for instance, the RSF killed more than fifty inhabitants of villages and town perceived as sympathetic to the SAF. In East Al Gezira, reprisals by the RSF following the desertion of one of their senior commanders saw hundreds of civilians killed, including up to 124 in Al Sireha town alone, with particular targeting of those from the senior commander’s tribe. The RSF entered villages and towns firing indiscriminately at residents with heavy machine guns.120Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Rapid Support Forces Target Civilians’; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 34–35.

The SAF also engaged in ethnic and retaliatory attacks against unarmed civilians in villages with ethnic Kabani. At least twenty-six civilians including a child were killed in Tayba village and sixteen others in Dar al-Salam al-Hideba village.121‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 36. The SAF similarly targeted the Arab Rizeigat community in Senmar for perceived support to the RSF.122Ibid, para 39. On Christmas Day 2025, an attack on the village of Julud in the Nuba Mountains region of South Kordofan State killed twelve and injured nineteen Christians who were celebrating the day.123‘Christmas Celebration Bombed in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains’, Sudan War Monitor, 3 January 2026.

Attacks against markets

The SAF conducted airstrikes on markets in areas controlled by the RSF, often alleging a military presence (that might or might not exist).124‘Sudan Media Forum: Hunger, shelling, airstrikes scourge Sudan’s civilians’. Even if soldiers were present, the attacks may violate the IHL rules of proportionality and precautions in attack. On 1 June 2025, for instance, the SAF hit the main market in Al Koma in North Darfur, near El Fasher, during peak hours, killing dozens of civilians and injuring many others, including market vendors, women, and children. An earlier attack on the same market in October 2024 killed at least 45 civilians and wounded many hundreds.125Sudan War Monitor, ‘Airstrike kills dozens in Darfur Market’, 3 June 2025; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 81. The following month, airstrikes in Omdurman, including on Gandahar Markat in Ombada, killed at least 62 civilians and injured 200 others, reportedly with the use of barrel bombs, decimating shops and homes.126Sudan INGO Forum, ‘INGOs working in Sudan sound alarm on increasing use of explosive weapons in heavily populated civilian areas’, 8 November 2024.

In December 2024, a wave of SAF attacks launched on busy markets killed up to 200 civilians. In one, the SAF dropped eight bombs on the market in Kabkabiya on 9 December 2024, killing up to 100 and injuring dozens more. The market was destroyed and several shops were burned down.127Sudan War Monitor, ‘Sudanese Air Force kills nearly 200 civilians in attacks on markets’, 10 December 2024; Amnesty International, ‘Sudan: SAF airstrike on crowded market a flagrant war crime’, 12 December 2024; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 82 The SAF justified these attacks as targeting sites and facilities used by the RSF. In particular, the SAF claimed to have targeted ‘gatherings’ in Kabkabiya, inflicting damage on a combat vehicle with its crew and commander (lieutenant colonel) as well as on a truck carrying weapons and ammunition. According to neutral local sources, most of the victims appeared to be civilian vendors, including women and children. Although RSF fighters are occasionally present in markets, they are mainly frequented by civilians.128Sudan War Monitor, ‘Sudanese Air Force kills nearly 200 civilians in attacks on markets’; Amnesty International, ‘Sudan: SAF airstrike on crowded market a flagrant war crime’. Other attacks, such as the one on 24 March 2025 that struck Tora market, north of El Fasher, involved use by the SAF of imprecise barrel-bombs caused extensive civilian harm and killed livestock, disrupting food access. Sometimes, as was the case in Tora, the market was among the last accessible sources of food in the entire region.129‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 83.

The RSF also attacked markets during the reporting period, in particular shelling Sabreen market in Karari, Omdurman, on 23 September 2024 and again on 1 February 2025. Up to 60 civilians were killed and many others wounded as a result of these attacks.130Ibid, para 74. The RSF also repeatedly shelled local markets in North Darfur, particularly in El Fasher and its surroundings, notably the Al Mawashi livestock market on 3 and 4 July and 26 September 2024, killing more than 40 civilians and damaging the livestock market.131Ibid; and ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 32. Naivasha market in Abu Shouk camp was repeatedly bombed by the RSF – in August, November, and December 2024 and in January, March, May, and June 2025.132‘Shells fall on crowded markets in Darfur’, Radio Dabanga, 27 August 2024; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 74. Similarly, ground offensives launched by the RSF in 2024 and 2025 set ablaze markets and villages. In particular, during February 2025 ground offensive on Zamzam displacement camp (see above), the RSF burned down the majority of the market.133‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 75. The RSF and its allies destroyed and burned farmland and crops, particularly in eastern Darfur at the end of 2024 and then in the vicinity of El Fasher in April 2025.134Ibid, para 78.

Attacks against medical and humanitarian personnel

Even though both parties to the conflict have deliberately targeted medical personnel, the RSF account for the vast majority of such attacks – 159 were recorded since the beginning of the conflict by September 2025.135Human Rights Watch, ‘“Khartoum is not Safe for Women!”’; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 98. In January 2025 alone, four attacks on medical facilities killed a total of seventy medical personnel and wounded twenty-one.136OCHA, ‘Sudan, Humanitarian Access Snapshot: January 2025’, 17 February 2025. While transferring patients to El Fasher, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) ambulance staff were shot at on 24 December 2024 and again on 10 January 2025.137‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 98. On 11 April 2025, the RSF killed ten staff of the medical clinic and injured several others in Zamzam camp – it was the only clinic still operating there.138P. Wintour, ‘More than 200 civilians killed as Sudan’s RSF attacks Darfur displacement camps’, The Guardian, 13 April 2025; International NGO Safety Organisation, ‘Two years of conflict in Sudan, marked by continued attacks on civilians and aid workers’; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 98. These attacks on civilians are also serious violations of the special protection IHL affords to medical personnel.139ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 25: ‘Medical Personnel’.

From July 2024 to April 2025, the International NGO Safety Organisation recorded 103 incidents impacting humanitarian workers in Sudan, including thirty distinct attacks.140International NGO Safety Organisation, ‘Two years of conflict in Sudan, marked by continued attacks on civilians and aid workers’. WFP staff were killed by an aerial bombardment that struck the agency’s field office in Yabus on 19 December 2024, and other WFP personnel were among those killed and injured by the drone attack on a joint WFP-UNICEF convoy on 2 June 2025. Responsibility for the December 2024 attack appears to rest with the SAF, while the June 2025 attacks are presumed to be attributable to the RSF who controlled the area and are known to use drones extensive for such operations. In May 2024, a convoy of three ICRC vehicles was attacked in Layba in South Darfur, killing two ICRC drivers and injuring three other staff.141‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 107. According to the ICRC, ‘Sudan has been one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a Red Cross/Red Crescent worker’.142ICRC, ‘“We have nothing to go back to” – two years of devastation in Sudan’, p 11.

Starvation as a method of warfare

Attacks on food systems, coupled with the impediment of humanitarian relief and the imposition of sieges in certain localities have resulted in the world’s largest hunger crisis, with approximatively 25 million people – half of Sudan’s population – facing acute hunger, and 5 million women and children suffering from malnutrition at the end of the reporting period.143WFP, ‘WFP calls for humanitarian access, as Sudanese city grapples with starvation’, 13 August 2025. People trapped in conflict-affected areas and in displacement camps have been at particular risk of starvation.144‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 56.

On 1 August 2024, the IPC’s Famine Review Committee declared that the situation in Zamzam camp – home to hundreds of thousands of IDPs – amounted to famine.145IPC, Combined Review of (i) the Famine Early Warning System Network System Network (Fews Net) IPC Compatible Analysis for IDP Camps in El Fasher, North Darfur; and (ii) the IPC Sudan Technical Working Group Analysis of Zamzam Camp North Darfur, Sudan, Report, 1 August 2024, p 2. Siege-like conditions inside the camp146OHCHR, ‘Sudan: UN Fact-Finding Mission Deplores Darfur Killings as Conflict Enters Third Year, Warning “Darkest Chapters” May Lie Ahead’, 14 April 2025; UNICEF, ‘Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No 30 – April 2025’, 29 May 2025, p 2; Sudanese American Physicians Association (SAPA), ‘SAPA Launches Critical Humanitarian Project in Zamzam Camp with Funding from the Schmidt Family Foundation’, 2 October 2024. and restrictions on humanitarian aid imposed by the RSF were said to be the main driving forces behind this.147WFP, ‘Famine confirmed in Sudan’s North Darfur, confirming UN agencies worst fears’, 1 August 2024. By blocking delivery of food, medicine, and other essential supplies, the RSF also prevented the treatment of thousands of children suffering from acute malnutrition in the camp.148‘North Darfur supply blockade stalls treatment for 5,000 malnourished children’, Radio Dabanga, 13 October 2024.

Since the famine was first confirmed in August 2024, the situation has further deteriorated owing to the active besieging of civilian areas and restrictions on food supplies imposed by parties to the conflict, primarily the RSF but also the SAF. Famine and hunger spread across Darfur, and in December 2024, the IPC assessed that famine had also occurred in Abu Shouk and Al Salam camps, as well as in the Western Nuba mountains in South Kordofan state, and projected this would continue and expand to other localities in North Darfur, including Al Lait, At Tawisha, El Fasher, Melit, and Um Kadadah.149Famine Review Committee: Sudan, December 2024’, 24 December 2024, p1. The rising food and supply crisis in Dilling (South Kordofan) was caused and exacerbated by intense fighting and siege conditions imposed by the RSF and SPLM-N al-Hilu for more than nine months.150‘Sudanese Army Airdrops Aid into Starving City of Dilling, South Kordofan’, Darfur24, 30 August 2024; ‘Sudanese military closes to breaking two-year siege of Dilling’, Sudans Post, 28 may 2025; UNICEF, ‘After months of siege, UNICEF convoy reaches South Kordofan with lifesaving supplies for children’, Press release, 24 August 2025. With child mortality of two deaths a day, the SAF decided to airdrop aid in late August 2024.151‘Sudanese Army Airdrops Aid into Starving City of Dilling, South Kordofan’, Darfur24, 30 August 2024.

The RSF siege of Dilling city also resulted in a sharp increase in malnutrition cases, rising from a reported 190 in June 2024 to 917 by September, although the actual figures were expected to be far higher.152‘Malnutrition Cases Sharply Rise in Dilling, South Kordofan’, Darfur24, 16 September 2024. Residents are reported to have resorted to eating tree leaves, leather, and animal feed to survive.153‘Sudan’s Dilling faces famine as war isolates South Kordofan’, Radio Dabanga, 27 June 2024. People trapped in El Fasher likewise faced starvation, as all trade routes and supply lines were blocked for over a year, preventing food deliveries. Some families in the city resorted to eating animal fodder and food waste to survive.154WFP, ‘One year after famine first confirmed in Sudan, WFP warns that people trapped in El Fasher face starvation’, 5 August 2025.

Sieges are not per se unlawful under IHL, provided their purpose is only to achieve a military objective and not to starve the civilian population. But the prohibition of starvation of civilians as a method of warfare and the protection of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population are enshrined in treaty and custom.155Art 14, Additional Protocol II; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 53: ‘Starvation as a Method of Warfare’. Given that the inhabitants were not permitted to leave, and that foodstuffs and other essential supplies were not allowed to enter the besieged areas, the RSF’s actions are likely war crimes.

In addition to attacks and insecurity that forced humanitarian organizations repeatedly to suspend or reduce their operations, access restrictions as well as bureaucratic and administrative burdens imposed by both the SAF and the RSF have considerably impeded the delivery of humanitarian assistance.156Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Rapid Support Forces Target Civilians’; International NGO Safety Organisation, ‘Two years of conflict in Sudan, marked by continued attacks on civilians and aid workers’; ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 56–57; Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 193; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 110. Humanitarian agencies have been denied or faced significant delays in securing visas and permission to travel, have been forced to accept armed escorts (at high cost); aid has been diverted (or looted), and efforts were made to interfere in prioritization and beneficiary selection.157OCHA, ‘Sudan Humanitarian Access Snapshot: July 2024’, 5 August 2024; OCHA, ‘Sudan Humanitarian Access Snapshot: September 2024’, 30 October 2024; OCHA, ‘Sudan Humanitarian Access Snapshot: November 2024’, 16 December 2024; OCHA, ‘Sudan, Humanitarian Access Snapshot: February 2025’, 13 March 2025; ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, paras 56–57 ; UNMAS, ‘Sudan’, May 2025; OCHA, ‘Sudan: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (June 2025)’, 8 July 2025.

The SAF prevented trucks loaded with food aid from entering the country through the main crossing from Chad into Sudan at Adré. The Adré crossing was closed from February to August 2024, following an order issued by the Sudanese government that claimed the measure was to stop weapons smuggling.158D. Walsh, ‘As Starvation Spreads in Sudan, Military Blocks Aid Trucks at Border’, The New York Times, 26 July 2024 (updated 25 November 2024); ‘Sudan to open Adre border crossing to facilitate humanitarian aid access’, UN News, 16 August 2024; ‘Sudan extends opening of Adre crossing for aid delivery’, Reuters, 13 November 2024. To comply with the order, trucks were required to take a 200-mile detour to Tine, a crossing controlled by a militia allied with the SAF, through which they could enter Darfur. Since the diversion was both dangerous and expensive and took up to five times longer than transiting through Adré, only a small fraction of the trucks carrying food were getting through (320 instead of the thousands that were needed). During the closure of the Adré crossing, the number of people facing acute malnutrition or starvation rose from 1.7 million to 7 million.159D. Walsh, ‘As Starvation Spreads in Sudan, Military Blocks Aid Trucks at Border’. Although the re-opening of Adré crossing improved the movement of relief supplies, humanitarian access to Darfur has continued to be impeded. Thus, the same month the crossing reopened, dozens of trucks in Al Gezira, Darfur, and Khartoum were denied access or delayed.160OCHA, ‘Sudan Humanitarian Access Snapshot: September 2024’, 30 October 2024; ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 57.

Parties to a NIAC are required by IHL to ‘allow and facilitate the rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief for civilians in need, which is impartial in character and conducted without any adverse distinction, subject to their right of control.’161ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’. While humanitarian relief is subject to the consent of the parties concerned, that consent may not be withheld arbitrarily.162M. Sassòli, International Humanitarian Law: Rules, Controversies, and Solutions to Problems Arising in Warfare, 2nd Edn,Edward Elgar, 2024, para 10.240.

Attacks against displaced persons and forced displacement

As a result of the intense shelling and attacks on IDP camps by the RSF, many displaced civilians were killed, injured, or re-displaced.163‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 45. For instance, since early 2025, the RSF intensified artillery strikes on the Abu Shouk camp, which shelters civilians especially from non-Arab communities. The attacks killed more than 300 and injured many others, triggering mass displacement.164‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 26. Likewise, Zamzam camp was increasingly and repeatedly shelled by the RSF starting in May 2024, apparently on ethnic grounds as the RSF consider certain communities, particularly the Zaghawa, to be allied with the SAF and the Darfur Joint Protection Forces. According to a witness, the RSF ‘burned everything. They claimed they only wanted to fight soldiers, but they punished the whole community. It felt like they wanted to remove us because of who we are’. When storming the camp on 11 and 12 February 2025, the RSF killed at least 30 people and injured 21 others.165Ibid, para 27.

During a ground offensive on the camp from 11 to 13 April 2025, the RSF and their allies fired indiscriminately at residents, killing hundreds. The RSF alleged the camp was being used for military purposes by the SAF, a claim refuted by residents and humanitarian groups.166‘Sudan’s RSF claims control of major Darfur camp, civilians flee’, Reuters, 14 April 2025; Husham, ‘“A tree is worth more”: Sudanese civilians fleeing RSF attacks on Zamzam’. As a result of the attacks, more than 400,000 inhabitants (around eighty-one per cent of the camp’s population) were again displaced, fleeing towards Tawilah or back to El Fasher.167Wintour, ‘More than 200 civilians killed as Sudan’s RSF attacks Darfur displacement camps’; Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 28. Abu Shouk camp endured almost daily artillery shelling from the RSF, similarly forcing many of its 190,000 inhabitants to flee.168‘At least six killed, 20 wounded in shelling of Sudan’s El Fasher camp’, Sudan Tribune, 6 May 2025. Fleeing civilians were also attacked by the RSF on roads or at checkpoints. For instance, in mid-January 2025, the RSF attacked a civilian convoy of dozens of vehicles close to the Chadian border. Although the convoy had been assured safe passage through areas controlled by the RSF and was escorted by neutral forces, at a checkpoint at the entrance of Kabkabiya, the RSF stopped the convoy and fired at it. Civilians tried to escape, but thirty were murdered.169Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 29.

The siege of the city of El Fasher, which started in May 2024, and related attacks caused the displacement of more than 470,000 from the city and its surrounding displacement camps (Abu Shouk, Shagra, and Zamzam camps).170‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 37; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 25. The area experienced successive waves of displacement in spring 2025. First, intensified fighting in and around El Fasher in March forced thousands to flee to Zamzam camp.171‘Sudan: Civilians targeted as hostilities intensify in the capital’, UN News, 20 March 2025. Then, in mid-April 2025, after the RSF seized the Zamzam camp following a four-day assault that left hundreds dead or wounded, tens of thousands of camp residents fled on foot to El Fasher. At the same time, El Fasher came under heavy shelling and RSF ground attacks. The RSF alleged that the camp had been used for military purposes, denied targeting civilians, and claimed to have organized voluntary evacuations for those fleeing El Fasher and nearby displacement sites.172‘Shelling kills three at Darfur IDP camp; RSF assault on El Fasher feared’, Sudan Tribune, 7 April 2025; ‘Sudan’s RSF claims control of major Darfur camp, civilians flee’, Reuters, 14 April 2025. However, humanitarian actors and residents reported attacks on and violence against vulnerable civilians, including women, children, and older persons.173‘Sudan’s RSF claims control of major Darfur camp, civilians flee’, Reuters, 14 April 2025; Husham, ‘“A tree is worth more”: Sudanese civilians fleeing RSF attacks on Zamzam’, Al Jazeera, 27 April 2025.

Forced displacement in Sudan is thus a dire concern. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the conflict between the SAF and the RSF has caused internal displacement of 10 million and forced a further 4.2 million to seek safety in neighbouring countries by the end of the reporting period.174IOM, ‘DTM Sudan Mobility Update (19)’, 8 July 2025. As a result, Sudan has been described as ‘the largest displacement crisis in the world’.175Amnesty International, ‘“They raped all of us”: Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in Sudan’, 10 April 2025, p 5. Forced displacement is only permissible under IHL where the security of civilians or imperative military reasons (such as clearing a combat zone) require the temporary evacuation from the area of the civilian population. Under no circumstances can the persecution of the civilian population justify its removal.176Art 17, Additional Protocol II; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 129: ‘The Act of Displacement’. Once displacement occurs, all possible measures must be taken in order that displaced civilians are provided with satisfactory conditions, for example of shelter and food but also of safety.177ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 131: ‘Treatment of Displaced Persons’. They must be respected and protected.

Alleged use of chemical weapons

Reports indicate that the SAF used chemical weapons against the RSF in 2023 and 2024, leading the United States to impose sanctions on Sudan on 22 May 2025 under its domestic Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act of 1991.178US Department of State, ‘Imposing Measures on Sudan for its Use of Chemical Weapons’, Press statement, 22 May 2025; S. Lewis and D. Psaledakis, ‘US to impose sanctions on Sudan after finding government used chemical weapons’, Reuters, 23 May 2025. According to reports, in addition to using a riot-control and vomiting agent (chloropicrin) as a method of warfare in Omdurman in September 2023, the SAF used chlorine gas against RSF positions on two occasions in late 2024 in remote areas of Sudan.179D. Walsh and J. E. Barnes, ‘Sudan’s Military Has Used Chemical Weapons Twice, U.S. Officials Say’, The New York Times, 16 January 2025; ‘Written statement submitted by Coordination des Associations et des Particuliers pour la Liberté de Conscience, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status’, UN Doc A/HRC/59/NGO/316, 30 June 2025, p 3. Chlorine can kill and, in survivors, cause lasting damage to human tissue and severe respiratory pain.180‘US says Sudan used chemical weapons, imposes sanctions’, Le Monde, 22 May 2025; Lewis and Psaledakis, ‘US to impose sanctions on Sudan after finding government used chemical weapons’.

Use of chlorine gas in warfare against anyone, military or civilian, is similarly prohibited under the 1992 Chemical Weapons Convention181Arts I (b)-(c) and II, Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction; adopted at Geneva, 3 September 1992; entered into force, 29 April 1997. See also ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 74: ‘Chemical Weapons’. to which Sudan is a State Party. Few members of the SAF were reportedly aware of the chemical weapons programme in Sudan, but, according to two US officials speaking on condition of anonymity, General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, the leader of the SAF, authorized the use of chemical weapons.182Walsh and Barnes, ‘Sudan’s Military Has Used Chemical Weapons Twice, U.S. Officials Say’. Sudan rejected the allegations,183Letter dated 24 May 2025 from the Permanent Representative of the Sudan to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council, UN Doc S/2025/325, 27 May 2025. instead accusing the RSF of employing chemical weapons. It also criticized the United States for failing to submit the claim to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), while, in Khartoum’s view, ignoring crimes committed by the RSF.184Walsh and Barnes, ‘Sudan’s Military Has Used Chemical Weapons Twice, U.S. Officials Say’; Lewis and Psaledakis, ‘US to impose sanctions on Sudan after finding government used chemical weapons’; ‘Sudan denies using chemical weapons in civil war after US imposes sanctions’, France 24, 23 May 2025.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

Persons in the power of the SAF and RSF were subjected to a series of abuses, including executions, torture, arbitrary deprivation of liberty, and sexual and gender-based violence. In several cases, these IHL violations were motivated by ethnic considerations and/or alleged affiliations.185‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, para 10. These amounted to both war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Murder of civilians and persons hors de combat

Murder was prevalent during the reporting period, notably in connection with torture. On 7 March 2025, a mass grave was found at a RSF base near the village of Garri after it was retaken by the SAF. There were at least 550 unmarked burial sites, many of which contained multiple bodies. The detainees had been tortured or starved to death.186M. Townsend, ‘Evidence of torture found as detention centre and mass grave discovered outside Khartoum’, The Guardian, 7 March 2025. In 2024, multiple incidents were documented of unarmed enemy soldiers being summarily executed by both the RSF and the SAF and, in some cases, subsequently mutilated.187Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Warring Parties Execute Detainees, Mutilate Bodies’. At the end of April 2025, a group between fifteen and twenty-five male detainees were beaten with sticks and whips and then shot dead by the RSF in Salha (Omdurman).188‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 50.

Numerous incidents involved fleeing civilians, including women and children, being killed on the road or at checkpoints by the RSF. The main victims of these violations were members of non-Arab community (Fur, Masalit, Tunjur, and Zaghawa).189Ibid, para 30; see also Z. M. Salih, ‘“If you are black, you are finished”: the ethnically targeted violence raging in Sudan’,The Guardian, 10 January 2025. In the course of retaliatory attacks following the defection of the Commander Abu Agla Keikel in late October 2024, the RSF rounded up and executed men and boys in Al Sihera, targeting those it perceived as having been affiliated to him. In videos recorded by the RSF, some detainees appeared with bloodstained clothing or were forced to mimic animal sounds. The fate of the male detainees appearing on the videos remains unknown, but piles of bodies were spotted by fleeing residents, while satellite imagery suggest that new graves had appeared in the village in the aftermath of the attack.190Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Rapid Support Forces Target Civilians’.

Summary execution of IDPs has occurred particularly in RSF-controlled areas. During the ground offensive by the RSF and allies against Zamzam camp in mid-April 2025, which left hundreds, if not thousands, dead (mostly women and children), actual or perceived members and associates of the SAF and their allies were summarily executed by the attackers.191Wintour, ‘More than 200 civilians killed as Sudan’s RSF attacks Darfur displacement camps’; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 28. On 27 April 2025, the RSF reportedly executed 31 civilians, including children, in Omdurman, accusing them of affiliation with the SAF.192‘Sudan Doctors Network accuses RSF of ‘war crimes’ after 31 killed’, Al Jazeera, 27 April 2025.

The SAF were involved in similar atrocities. In areas recaptured by the SAF and its allies between September 2024 and January 2025, reports of extrajudicial executions of RSF members and alleged supporters emerged, notably in Al-Dinder and Sinja (Sennar state), and Wad Madani (Al Gezira state).193OHCHR, ‘Sudan: UN Fact-Finding Mission deplores Darfur killings as conflict enters third year, warning “darkest chapters” may lie ahead’, Press release, 14 April 2025. In mid-January 2025, when the SAF retook Wad Madani, a male civilian was beaten and then thrown from a bridge and shot. One of the perpetrators was recorded as saying ‘this is in revenge for all our martyrs’.194‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 37. Similar incidents occurred when the SAF and allied groups advanced towards and retook Khartoum, Omdurman and Bahri from January to late March 2025. Civilians were beaten, insulted, and killed by the SAF and their allies – accused of being members of the RSF.195OHCHR, ‘Sudan: UN Fact-Finding Mission deplores Darfur killings as conflict enters third year, warning “darkest chapters” may lie ahead’; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 38. In some instances, bodies were subsequently mutilated.196Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Warring Parties Execute Detainees, Mutilate Bodies’. For instance, on 25 March 2025, in Umbada (south Omdurman), a man in civilian clothes decapitated the body of one of the six individuals executed by soldiers and brandished his head.197‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 38.

Torture

Both the SAF and RSF and their allies have engaged in a consistent pattern of torture and other forms of ill-treatment against both civilians and military personnel who were hors de combat.198Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: Warring Parties Execute Detainees, Mutilate Bodies’; IIFFM October 2024 report, paras 256, 258. The SAF beat and lashed their victims with iron cables, whips, and firearms, slashed their fingers and pulled out their toenails,199Ibid, para 259. while the RSF commonly lashed and beat their victims with cables, whips, and firearms.200Ibid, para 260. Victims reported being blindfolded and often lost consciousness due to the pain and suffering they endured.201Ibid, paras 259–61; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 47. The torture inside detention centres, operated by both the SAF and RSF, would sometimes be inflicted for hours at a stretch or even in some instances days.202IIFFM October 2024 report, paras 251–52, 259–63; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 47 and 52. See also Townsend, ‘Evidence of torture found as detention centre and mass grave discovered outside Khartoum’; M. Townsend, ‘“Here you will die”: detainees speak of executions, starvation and beatings at hands of Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces’, the Guardian, 7 March 2025.

Detainees were held in overcrowded cells (some prisoners had to sleep standing), systematically deprived of food, water, and medical care, sometimes leading to their deaths.203IIFFM October 2024 report, paras 248–50 and 252; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 48 and 54. See also: Townsend, ‘Evidence of torture found as detention centre and mass grave discovered outside Khartoum’; and Townsend, ‘“Here you will die”’. In 2024, young boys were among the victims, and, in some cases, they were forced to participate in torture themselves.204IIFFM October 2024 report, paras 263–64. The RSF’s Soba prison in Khartoum has been described by detainees as a ‘slaughterhouse’, with at least fifty detainees said to have died from torture and inhumane conditions between June and October 2024.205‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 48. One victim detained by the SAF in Serkab prison (Karari, Omdurman) was hit with an hammer, forced to sit naked on a metal chair, with weights attached to his genitals, and subject to electric shocks.206Ibid, para 53. Arrests and interrogations by the SAF were typically based on suspicion of collaboration or association with the RSF.207Ibid, paras 51 and 53.

In several incidents of sexual and gender-based violence (see below), the women and girls were sexually assaulted by RSF soldiers in front of their family members which added to “the trauma experienced by family members who witnessed the attacks. This also compounded stigma and other social consequences for survivors’ and relatives.208Amnesty International, ‘“They raped all of us”: Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in Sudan’, pp 22–23. See also: ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 29. All these abuses were often committed for the purpose of intimidation, coercion, punishment, or to obtain confessions, as well as on discriminatory bases such as ethnicity, making the ill-treatment punishable as the war crime of torture.209IIFFM October 2024 report, paras 240, 243, 258, 262, and 265; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 55. See also: Townsend, ‘“Here you will die”’.

Arbitrary deprivation of liberty and hostage-taking

During the reporting period, arbitrary deprivation of liberty has continued to be a major concern, with many civilians subjected to these practices by the SAF and RSF. Many instances of hostage-taking have been also recorded.210‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 44 and 55–57.

In areas under RSF control – particularly Darfur and Khartoum, as well as other localities – civilians were arrested, most often in their homes or at checkpoints. Arrests were made upon allegations of collaboration with the SAF, including on ethnic grounds, on the basis of information obtained from other civilians, whether for personal benefit or through torture, after preventing the RSF from abducting women and girls or looting, or on the basis of accusations of cattle theft or other crimes.211‘Recommendations for the protection of civilians in the Sudan: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/759, para 11; Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Detention and Ransom of Four IDPs by RSF in South Darfur’, 16 December 2024; Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Kalma IDP Camp, South Darfur State – Nyala’, 10 January 2025; ‘RSF Resorts to Kidnapping as a Tool of War and Revenue in Ransoms’, Atar Sudan in Perspective, No. 23, 3 March 2025, pp 2–3; Townsend, ‘“Here you will die”’; E. Hushman, ‘Two friends, one war and the RSF’s reign of terror in Khartoum’, Al Jazeera, 27 July 2025; ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 45–46. Civilians who remained in Khartoum after it came under the control of the RSF were also targeted while trying to reach markets to buy food.212K. Ahmed, ‘‘No One Recognised Him, Even as He Said His Name’: Last Video of Rescued Man Shows Horror of Sudan Torture Camps’, The Guardian, 9 April 2025. Civilians were detained secretly in various detention facilities, some of which were improvised, and none was charged, appeared before a court, or had access to legal representation or means of communication.213‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, paras 45–46.

The SAF released hundreds of military and civilian prisoners from detention facilities previously controlled by the RSF in Khartoum and White Nile state, where around 4,700 prisoners were held in appalling conditions (several dying as a result).214‘Sudan army’s latest major capture, al-Burhan says, “victory not complete”’, Al Jazeera, 29 March 2025. Similarly, the RSF detained significant numbers of male youths in El Fasher in 2024 upon suspicion of their being informants.215‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 36. Their fate remains unknown.

In turn, in areas retaken by the SAF or at checkpoints manned by them, people who had been living under the control of the RSF were arrested and detained on the grounds they were associated with the RSF. They were then reportedly held incommunicado without due process or judicial review, with the exception of one individual who appeared before a judge and was subsequently released after more than two months in detention.216‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 51. In Khartoum, over which the SAF gained full control on 7 April 2025, civilians accused of collaborating with the RSF were subjected to mass arrest with some summarily executed or with their fate unknown.217OHCHR, ‘Sudan: UN Fact-Finding Mission deplores Darfur killings as conflict enters third year, warning “darkest chapters” may lie ahead’, Press release, 14 April 2025. Since May 2024, the DJPF also conducted widespread arbitrary arrests of people suspected of collaborating with the RSF in El Fasher, notably young males, human rights activists, and journalists. Arab youths were specially targeted.218‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan’, UN Doc S/2025/239, para 36.

Reports indicate that in several instances, the RSF and affiliated groups demanded substantial ransom payments (US$1,000 or more) for the release of detainees (including, on occasion, doctors), who were tortured or otherwise ill-treated until the ransom was paid.219Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Detention and Ransom of Four IDPs by RSF in South Darfur’, 16 December 2024; RSF Resorts to Kidnapping as a Tool of War and Revenue in Ransoms’, Atar Sudan in Perspective, No 23, pp 2–6; Hushman, ‘Two friends, one war and the RSF’s reign of terror in Khartoum’. Some detainees were released after giving all their belongings to their captors.220Hushman, ‘Two friends, one war and the RSF’s reign of terror in Khartoum’. Others were freed after their families paid the ransom.221‘RSF Resorts to Kidnapping as a Tool of War and Revenue in Ransoms’, Atar Sudan in Perspective, No. 23, 3 March 2025, p 2, ‘Sudan: A War of Atrocities’, para 49. A steady rise in abductions has been observed, mainly by the RSF and affiliated groups, with displacement camps, particularly in Darfur, becoming regular sites for kidnappings of members of ethnic groups such as the Dajo, Fur, and Zaghawa.222Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘RSF Uniformed and Armed Men Kidnap Youth in East Darfur, Demand Ransom for His Release:’, 31 October 2024; Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Detention and Ransom of Four IDPs by RSF in South Darfur’, 16 December 2024; RSF Resorts to Kidnapping as a Tool of War and Revenue in Ransoms’, Atar Sudan in Perspective, No. 23, pp 4–6. Ransom payments were sometimes used to acquire weapons or sustain logistical and other military needs.223Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Detention and Ransom of Four IDPs by RSF in South Darfur’, 16 December 2024. Deprivation of liberty has sometimes been linked to sexual violence or forced recruitment, with some of the victims being teenagers.224Darfur Network for Human Rights , ‘RSF Uniformed and Armed Men Kidnap Youth in East Darfur, Demand Ransom for His Release:’, 31 October 2024; ‘RSF forcibly recruits from Darfur camp amid mounting losses’, Sudan Tribune, 15 November 2024; ‘RSF accused of forced recruitment, sparking fear and displacement in Darfur’, Sudan Tribune, 11 December 2024; Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Detention and Ransom of Four IDPs by RSF in South Darfur’, 16 December 2024; Darfur Network for Human Rights, ‘Kalma IDP Camp, South Darfur State – Nyala’, 10 January 2025; ‘RSF Resorts to Kidnapping as a Tool of War and Revenue in Ransoms’, Atar Sudan in Perspective, No 23, pp 3–5.