Conflict Overview

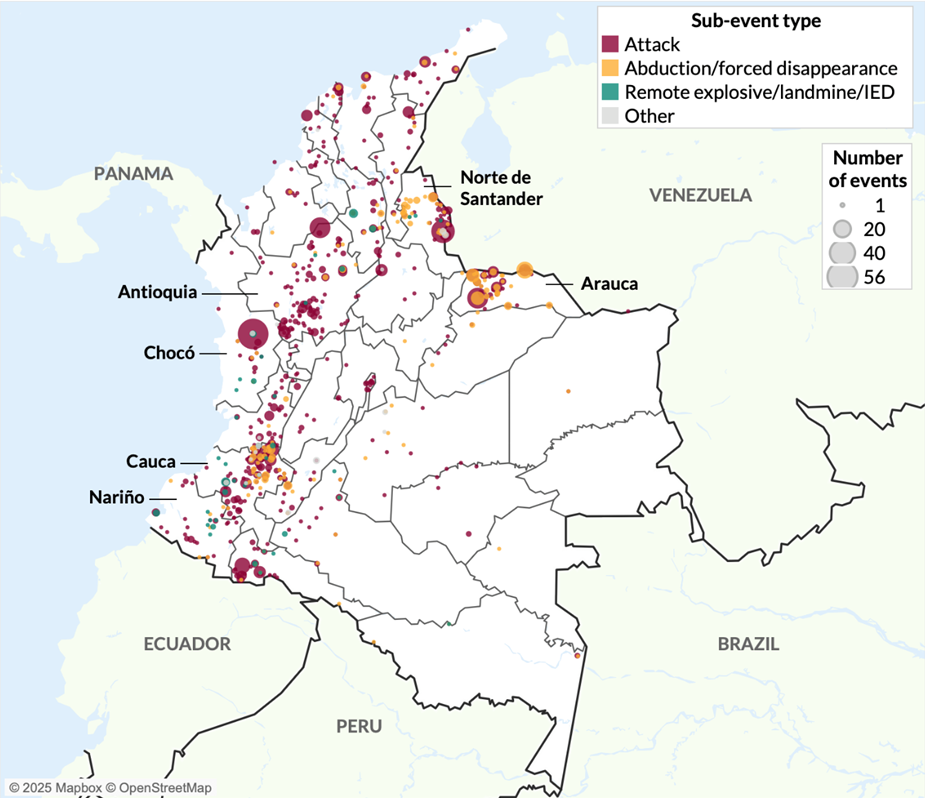

The armed conflicts in Colombia trace back to 1964 when two guerrilla movements were created to fight the government and the State armed forces – the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP) and the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN). During the 1980s, disparate paramilitary groups emerged to combat these organizations, and in 1997, they consolidated as the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC). Although the AUC collectively demobilized between 2004 and 11 April 2006,1Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición, ‘La Desmovilización de las AUC’. former members created new armed groups, notably the Ejército Gaitanista de Colombia (EGC, also known as the Gulf Clan), which remains a party to non-international armed conflicts. All of Colombia’s many armed conflicts have been characterized by widespread violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) by the parties,Historical Memory Group,2 ‘Basta Ya! Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity, General Report Historical Memory Group’, 2016, p 36 ff. with Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities disproportionately affected.

A watershed in Colombia’s history occurred on 24 November 2016, when the government and the FARC-EP – then the largest non-State armed group in the country – signed a peace agreement after protracted negotiations in Havana.3European Union, ‘An Historical Peace Agreement in Colombia’, 23 April 2021. FARC-EP demobilization began in 2017 although dissident factions rejected the accord and continued to attack the authorities and rival armed groups. Today, the conflicts in Colombia are increasingly fragmented, with disputes and alliances between armed groups shifting over time as they compete for territorial control of areas previously occupied by the FARC-EP.

In November 2022, the Colombian government and the ELN began peace negotiations but the government suspended talks after a major attack on 16 January 2025 by the ELN in Catatumbo in the north-east of the country, which took place amid clashes with a dissident FARC-EP group.4S. Torrado, ‘Proceso de paz con el ELN: fin del cese al fuego, secuestro y suspensión de los diálogos con el Gobierno Petro’, El País, 6 February 2025. The resulting humanitarian consequences, which included many deaths and significant displacement of the population, were described as among the most severe in nearly three decades.5‘Catatumbo: así avanza la salida de la crisis, tras dos meses de escalada violenta’, El Espectador, 14 March 2025.

Armed groups have also forged alliances with organized crime groups in the departments of Arauca, Cauca, and Chocó; the Bajo Cauca region in Antioquia; and the south of the department of Bolívar, provoking humanitarian emergencies in both border and urban areas.6J. P. Contreras Ríos, ‘No ocurre solo en Catatumbo: las alarmas por desborde de desplazamiento forzado’, El Espectador, 17 February 2025.

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

In the reporting period, ten non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) took place in Colombia.7International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), ‘Humanitarian Report 2025 – Colombia’. Four involved the Colombian Armed Forces fighting a non-State armed group, as follows:

- Colombia v National Liberation Army (ELN)

- Colombia v Ejército Gaitanista de Colombia (EGC) (formerly, the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, AGC)

- Colombia v Estado Mayor Central (EMC), a dissident FARC-EP group8The EMC sprang from an original group of 60 or so FARC-EP members who did not adhere to the 2016 peace process. In 2024, after disagreements between EMC membership on the desirability of new peace negotiations with the Colombian government, the EMBF was formed as a splinter group. J. P. Contreras Ríos, ‘Así nació el grupo que se separó de Mordisco y que ahora negocia la paz con Petro’, El Espectador, 4 December 2024.

- Colombia v Comandos de la Frontera (CDF), another dissident FARC-EP group.

These four NIACs are governed by Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, Additional Protocol II of 1977 (to which Colombia adhered in 1995), and customary IHL. The criterion that the armed group exercise such territorial control as to be able to sustain military operations and to implement the Protocol was met throughout the reporting period.

Six other NIACs involved two non-State armed groups fighting each other:

- ELN v EGC

- ELN v EMC

- ELN v Frente 33 of the Estado Mayor de los Bloques y el Frente (EMBF)

- EMC v Frente 57 Yair Bermúdez

- EMC v EGC

- EMC v Segunda Marquetalia.

These NIACs are regulated by Common Article 3 and customary IHL. Although the requirement for territorial control could be met in each case,9As of June 2024, according to Human Rights Watch, the EGC was present in 392 municipalities; the ELN in 232; and dissident FARC-EP groups in 299. Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Events of 2024’, World Report 2025. for Additional Protocol II to apply one of the parties must be the armed forces of the State.10The material jurisdiction of the Protocol is limited to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups.…’ [added emphasis]. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II of 1977.

In 2024, as part of its ‘Total Peace’ (‘Paz Total’) policy, the Government announced negotiations and ceasefires with the ELN, the EMC, and the EGC.11The Colombian government’s ‘Total Peace’ policy was instituted under Law 2272 of 2022 as a strategic decision to seek peace with all armed groups active in the country. The policy also seeks implementation of previously concluded peace agreements. Departamento Nacional de Planeación, ‘Paz Total’, 16 June 2025. Even where agreements were reached, however, armed groups often failed to comply.12Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Events of 2024’.

Compliance with IHL

Overview

During the reporting period, the humanitarian situation in Colombia deteriorated significantly,13ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, 27 March 2025, p 3. with civilians increasingly the victims of serious violations of IHL. The civilian population was directly attacked, with some civilians murdered in cold blood or forcibly disappeared while others were used as human shields. Children continued to be forcibly recruited and used in combat. Sexual and gender-based violence, especially against women and girls, increased. Indiscriminate use of anti-personnel mines and remotely controlled improvised explosive devices (IEDs) killed or injured civilians, contributing to displacement. Restrictions on humanitarian access imposed by armed groups were often arbitrary in nature, while conditions for detainees continued to worsen.14Ibid, p 3 ff. The 9.3 million people living under the presence, influence and/or control of armed groups15United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Colombia: Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan: Update – Summary’, January 2025, p 4. were particularly exposed to these violations.

Civilian Objects under Attack

In 2024, civilian objects were frequently damaged in attacks and on some occasions were deliberately targeted.16Ibid, p 3. Under customary IHL, attacks may only be directed against military objectives and must not be directed against civilian objects.17ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. Military objectives are those objects which, by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action.18ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 8: ‘Definition of Military Objectives’. In addition, the object’s partial or total destruction, capture, or neutralization must offer a definite military advantage. Civilian objects are all objects that are not military objectives.19ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 9: ‘Definition of Civilian Objects’. Indiscriminate attacks – those not directed against a lawful military objective – are prohibited.20ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 11: ‘Indiscriminate Attacks’.

Special protection against attack is afforded to hospitals and other medical facilities under IHL,21ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 28: ‘Medical Units’. yet the United Nations documented 15 separate attacks on hospitals in Colombia in 2024.22‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 47. While many of the perpetrators could not be reliably identified, certain attacks on hospitals were attributed to FARC-EP dissidents (including the EMC), and, albeit to a lesser extent, the CDF, the EGC, and the ELN, as well as State armed forces.23Ibid.

Schools and education were particularly affected by the violence,24‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, 22 January 2025, para 19. with some badly damaged in the course of hostilities.25ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 3. The United Nations reported an increased number of attacks on schools in 2024, with 27 incidents recorded in total (88 if one includes threats and attacks on teachers, damage to infrastructure, or the emplacement of IEDs).26UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, 2025, p 8. The most affected areas were in Cauca and, to a lesser extent, the departments of Antioquia, Arauca, Norte de Santander, and Putumayo.27Ibid.

These and other incidents discussed below raise serious concerns regarding compliance with IHL by armed groups and, to a lesser extent, the State armed forces, in particular with the principles of distinction and proportionality in attack; the underlying duty to take precautions in attack with a view to avoiding and in any event minimizing damage to civilian objects; and the duty to ensure the special protection of medical facilities.

Civilians under Attack

Use of anti-personnel mines

Colombia remains one of the countries with the highest toll from anti-personnel mines worldwide. These victim-activated munitions are improvised by multiple armed groups.28Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), ‘Integrated Mine Action Program Phase 1: 2021-2025’. In 2024, mines killed or injured 108 people of whom 66 – almost two thirds – were civilian, indicating that considerable use was indiscriminate.29Colombia Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Article 7 Report (for 2024), p 63. Of particular concern was the increase in child casualties – the proportion rose from 12 per cent in 2023 to 23 per cent of the total in 2024.30Colombia, Article 5 deadline Extension Request under the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, 5 June 2025, p 4. In one incident in August 2024, a young girl lost her leg after stepping on an anti-personnel mine on the road between home and school in San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá).31‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 19. FARC-EP dissidents were said to be responsible,32C. Salazar, ‘Niña de 9 años resultó herida tras caer en un campo minado en San Vicente del Caguán, Caquetá’, Infobae, 24 August 2024. with both the EMC and Segunda Marquetalia active locally.33J. Sampier, M. R. Tortosa and E. Breyne, ‘Mapping and Profiling the Most Threatening Criminal Networks in Latin America and the Caribbean’, El Paccto, 2025, pp 25 and 74.

Anti-personnel mines can severely restrict the freedom of movement of civilians and prevent them from accessing essential services.34ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, Thematic report, 10 July 2025, p 12. They are known for their devastating long-term effects, which endure long after hostilities in an area have ended.35ICRC, ‘International humanitarian law and policy on anti-personnel landmines’. Thus, even if emplaced in strict compliance with IHL – a rare occurrence – the effects may still fall primarily on civilians. Far beyond the immediate impact on those who are killed or injured in a detonation, these munitions can displace or confine entire communities and undermine food security.36ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 4.

Fourteen Colombian departments were affected by explosive ordnance in 2024, with the Pacific region the most severely impacted – Cauca, Nariño, and Valle del Cauca combined accounted for 65 per cent of all casualties. For the first time in eight years, casualties were reported in Amazonas, signalling the spread of contamination to new areas.37Ibid, pp 3–5. As long as territorial control remains a key objective, mine use is expected to continue. Some armed groups that had not previously relied on landmines are now using them with a view to securing strategic corridors.38Mine Action Review, ‘Colombia’, Clearing the Mines 2025, Norwegian People’s Aid, November 2025.

Colombia is a State Party to the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, which comprehensively prohibits anti-personnel mines.39Art 1(1), Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention. Colombia became a State Party on 1 March 2001. As it is a disarmament treaty, it binds directly only State actors and not the armed groups in Colombia. Colombia is also, however, party to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons and its amended Protocol II of 1996, which applies to all parties to armed conflict, including non-State actors in a NIAC.40Art 1(2), Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998. Colombia adhered to the Protocol in 2000. Although the protocol does not ban all use of anti-personnel mines, it specifically prohibits their indiscriminate use and requires that a party to an armed conflict take all feasible precautions to protect civilians from their effects.41Art 3(8) and (10), 1996 Amended Protocol II. Likewise, customary IHL requires that ‘when landmines are used, particular care must be taken to minimize their indiscriminate effects’.42ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 81: ‘Restrictions on the Use of Landmines’.

Use of armed drones

Increased use of armed drones by armed groups raised serious concerns under the principle of distinction,43ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 1: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilians and Combatants’; and Rule 7: The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’. including the prohibition of indiscriminate attacks, as well as the principles of proportionality44ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 14: ‘Proportionality in Attack’. and precaution in attack.45ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 15: ‘Principle of Precautions in Attack’. Where civilians are deliberately targeted by a party to an armed conflict, this amounts to a serious violation of the principle of distinction and is likely to be a war crime. Where the Colombian military are targeted by armed drones in connection with one of the many armed conflicts, this may comply with the principle of distinction, but if excessive civilian harm may be expected to result when compared to the military advantage, an attack will be disproportionate and therefore unlawful.

During the reporting period, armed groups made widespread use of drones46ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 5. to drop explosive munitions, as well as for surveillance and reconnaissance, or to enforce confinement of civilians.47ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 12. The Colombian army reported 119 drone attacks in 2024, injuring thirty-two soldiers, seven police officers, and twenty-eight civilians.48S. Torrado, ‘Colombia on alert as dissident groups ramp up drone attacks’, El País, 1 September 2025. The use of drones reportedly increased by more than half in 2025 with around 180 attacks recorded.49Ibid. Cauca has been the most affected department: since 2024, armed groups, notably the EMC, have conducted nearly 100 daily drone operations and, by April 2025, they had mounted 245 drone attacks against Colombian security forces.50ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 12; Torrado, ‘Colombia on alert as dissident groups ramp up drone attacks’. Drone attacks, including by the ELN, have been also recorded in Arauca, Antioquia, Nariño, Norte de Santander, and Putumayo.51ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 5; Torrado, ‘Colombia on alert as dissident groups ramp up drone attacks’.

As armed groups use commercially available drones to deliver munitions, the attacks are imprecise, often resulting in civilian harm.52Ibid. In July 2024, a 10-year-old boy playing football in El Plateado (Cauca) was killed in a drone attack. This was reportedly the first such fatality. The explosion injured a further twelve people. According to the Colombian army, the attack, which was targeting its soldiers, was conducted by a faction of the EMC – a claim the faction denied.53Iván Velásquez Gómez, Post on social media site X, 24 July 2024; C. McGowan, ‘Ten-year-old boy killed in Colombia’s first drone death’, BBC News, 25 July 2024; ‘10-year-old boy on soccer field killed in “cowardly terrorist attack” targeting soldiers in Colombia’, CBS News, 25 July 2024.

Confinement and human shields

Reports indicate that armed groups have used civilians as human shields during armed confrontations, often in connection with the confinement of communities. Under IHL, use of human shields – the placing or moving of civilians to seek to prevent certain locations or forces from being targeted – is strictly prohibited.54ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 97: ‘Human Shields’. Deliberately using civilians to protect members of armed groups against attacks also violates the principle of distinction and the duty to separate civilians from military objectives whenever it is feasible to do so.55ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 23: ‘Location of Military Objectives outside Densely Populated Areas’; and Rule 24: ‘Removal of Civilians and Civilian Objects from the Vicinity of Military Objectives’.

Confinement of civilians, where civilians are prevented from leaving their communities or homes, results from incidental armed confrontations or the presence of explosive devices, as well as from a deliberate tactic used by armed groups to protect their forces against attacks.56J. F. Rodríguez, ‘Disidencias Farc estarían usando civiles como escudo en enfrentamientos en el Catatumbo’, W Radio Colombia, 23 March 2025; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025, Colombia’, p 6. In 2024, confinement increased markedly: a total of 138,419 civilians, most of whom were Indigenous or Afro-descendant, were said to have been confined.57‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 16. See also: ‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/968, 26 December 2024, para 39; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 6.

Confined civilians are prevented from accessing basic necessities,58ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, pp 13–16; L. Reynoso, ‘La contraofensiva de las disidencias de las FARC reaviva la crisis en el Catatumbo’, El País, 26 March 2025; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 6. as well as being at risk of being killed or injured, and, in the case of children, unlawfully recruited.59ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, pp 10–13. In Chocó alone, between January and April 2025, more than 26,000 people were reportedly confined,60Ibid, pp 10–11. while in 2024, the department accounted for forty-one per cent of the total number of confinements.61ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 6. Confrontations between armed groups, notably the ELN and the EGC,62‘“Paren esta guerra tan dura”: comunidades alertan por aumento de violencia en Chocó’, El Espectador, 9 February 2025. were described as the main cause of confinement.63ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 10. Community leaders reported armed group incursions into homes, with civilians sometimes forced to stand between opposing fighters.64‘“Paren esta guerra tan dura”: comunidades alertan por aumento de violencia en Chocó’. Similar practices were reported in 2024in Antioquia, Arauca, Bolivar, Caquetá, Cauca, and Putumayo.65ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 6.

In 2025, instances of confinements were also recorded in Catatumbo in Norte de Santander department, including in Tibú and El Tarra, where, on 20 March, Frente 33 of the EMBF members occupied homes and compelled residents, including women and children, to remain during the group’s combat with the ELN.66Rodríguez, ‘Disidencias Farc estarían usando civiles como escudo en enfrentamientos en el Catatumbo’. In the Amazon, ‘Campesino Guard’ units – unarmed self-protection groups – are said to have been deployed by the EMC to block military or police access to areas they control, preventing the military from entering these areas as they could not lawfully shoot unarmed farmers.67International Crisis Group, ‘Rebel Razing: Loosening the Criminal Hold on the Colombian Amazon’, 18 October 2024. The blockages are thought to be connected to illicit extraction of minerals in the Amazon and Orinoquia regions along the border with Venezuela.68‘Central General Staff – FARC Dissidents’, InSight Crime, 14 June 2024.

Forced displacement

Forced displacement remains the primary driver of humanitarian emergencies in Colombia.69OCHA, ‘Colombia: Informe de situación humanitaria 2024 – enero a noviembre de 2024’, 31 December 2024. Entire communities were sometimes forcibly displaced by the presence or emplacement of improvised anti-personnel mines in 2024. More often, civilians were compelled to flee due to direct threats, fear of recruitment (including of their children), or escalating violence. Displacement was fuelled by armed groups’ efforts to strengthen territorial control and through their competition for control of illicit activities.70Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘Emergencias humanitarias en Colombia hoy’, 16 February 2025. See also T. Breda, ‘“Total Peace” paradox in Colombia: Petro’s policy reduced violence, but armed groups grew stronger’, ACLED, 28 November 2024; ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 13. Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities were disproportionately affected, comprising around half of all those displaced.71‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 15; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 7.

In 2024, displacement occurred across 15 departments, including Antioquia, Bolivar, and Cauca, although Nariño remained the most affected.72ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 7. In February 2025 alone, more than 5,000 people were displaced due to fighting between armed groups in Colombia.73Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘Emergencias humanitarias en Colombia hoy’, 16 February 2025. In Chocó, clashes between the ELN and the EGC had displaced 3,600 civilians as of that month.74Contreras Ríos, ‘No ocurre solo en Catatumbo: las alarmas por desborde de desplazamiento forzado’. According to testimonies, armed groups barred civilians from returning home after work or school under threat of violence, claiming the area had to remain cleared for combat.75J. P. Contreras Ríos, ‘Los focos de violencia en el país que podrían desatar una crisis como en Catatumbo’, El Espectador, 8 February 2025.

Forced displacement has been especially acute in Catatumbo. According to community leaders, when fighting broke out between the ELN and Frente 33 of the EMBF, residents left their homes immediately and attempts to return were met with warnings from ELN members, including threats they would be killed or forcibly disappeared.76P. Mesa Loaiza, ‘Viaje al Catatumbo: así se vive la mayor crisis humanitaria de los últimos tiempos’, El Espectador, 26 January 2025.

In addition to displacements of groups or communities, an alarming rate of forced displacement of individuals or small groups due to threats, assassinations, extortion, intimidation, forced recruitment, or risks of sexual violence from armed groups was recorded in 2024. The most affected department was Valle de Cauca along with, albeit to a lesser extent, Antioquia, Bolivar, Cauca, Nariño, and Norte de Santander.77ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 7. See also Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘Colombia days in limbo amid escalating armed conflict’, 14 February 2025.

Under IHL applicable in NIACs, displacement of civilians for reasons related to the conflict is prohibited ‘unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand’.78ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 129: ‘The Act of Displacement’. Accordingly, although arguably certain instances of displacement fall within the narrow exceptions, such as clearing areas to protect civilians against hostilities, others involved civilians being forced to leave or having their movement restricted for other unlawful reasons or were conducted through threats of violence.

Humanitarian relief

In 2024, humanitarian access was severely curtailed in areas most affected by combat and where humanitarian needs were increasingly urgent. Under IHL, parties to a NIAC ‘must allow and facilitate the rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief for civilians in need, which is impartial in character and conducted without any adverse distinction, subject to their right of control.’79ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 55: ‘Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need’. While humanitarian relief is subject to the consent of the parties concerned, this consent cannot be withheld ‘arbitrarily’.80M. Sassòli, International Humanitarian Law: Rules, Controversies, and Solutions to Problems Arising in Warfare, 2nd edn,Edward Elgar, 2024, para 10.240. Armed groups have failed to comply with their IHL obligations to permit and facilitate humanitarian access on multiple occasions.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) recorded many restrictions on humanitarian access in 2025 – those placed upon humanitarian organizations and the population. A total of 127 incidents affecting 105,900 people were recorded between January and April 2025. This compares to 101 such events affecting 568,500 for the whole of 2024.81OCHA, ‘Colombia: Informe de Situación Humanitaria 2025 : Entre enero y abril de 2025’, 5 June 2025, p 2. Armed groups often accuse civilians of aiding one of their enemies, based solely on the fact that they had remained in their communities. Armed groups continued to restrict or deny relief on many occasions, claiming it would go to their enemies and not civilians in need.82ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 4; UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 4.

Protection of Persons in the Power of the Enemy

Murder of civilians and former fighters

In 2024, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) verified 72 incidents of ‘massacres’ – extrajudicial execution of at least three people – killing a total of 252.83‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 24. Human rights defenders, especially indigenous and community leaders and environmental defenders, as well as former FARC fighters continued to be the main victims of these war crimes, which were predominantly perpetrated by armed groups.84Ibid, para 28. Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples were also regularly targeted.85Ibid. According to data from the Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (INDEPAZ), between 1 July 2024 and 4 April 2025, 127 community leaders were killed across 89 municipalities in Colombia. Most of the victims were líderes comunales (community leaders), with thirty-seven recorded deaths, followed by twenty-two Indigenous leaders.86Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Indepaz), ‘Visor de Asesinato a Personas Líderes Sociales y Defensores de Derechos Humanos en Colombia’.

In Colombia, political opposition or social leadership is widely perceived as a threat to an armed group’s control of an area. The killing of human rights defenders, and in particular Indigenous and community leaders, serves to undermine community structures and erode civilian resistance, enabling the consolidation of territorial and social control.87‘Visit to Colombia: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay’, UN Doc A/HRC/57/47/Add.1, 10 September 2024, paras 57 and 58; ‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, paras 7, 13, 25, 28, and 29; B. M. Arango Jiménez, ‘Los patrones de persecución a líderes sociales después de la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz en el 2016’, Revista Nova et Vetera, Vol 7, No 66 (2021); ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 4. In 2024, of 122 human rights defenders killed, OHCHR assessed that 89 were targeted in relation to their work, with 71 per cent believed to have been killed by armed groups.88‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, paras 25–26. In a single territorial conflict between two armed groups in Arauca89Ibid, paras 28 and 29. – likely the ELN and the EMC, the main groups fighting in the region – twelve community leaders were murdered.90 ‘14 guerrilleros habrían muerto en combate entre ELN y FARC En zona rural del municipio de Arauquita’, News Radio, 13 August 2024; International Crisis Group, ‘Colombia’, June 2025; ‘Emergencias humanitarias en Colombia hoy’, Defensoría del pueblo: Colombia, 16 February 2025; J. D. Rodríguez, ‘Defensoría del Pueblo alerta por combates del ELN y disidencia de ‘Iván Mordisco’ en Arauca’, Infobae, 23 February 2025.

In the first half of 2025, 74 human rights defenders, including Indigenous and community leaders, were reported to have been murdered.91‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary General’, UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 38. Escalation in fighting between the ELN and the EMBF in Catatumbo since January coincided with multiple murders of community leaders. In just one month, armed groups killed three community leaders they perceived as a threat.92IMPACT, ‘Urgent Need for a Sustainable Response amid Escalating Violence and Persistent Insecurity in Catatumbo’, February 2025; Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘Defensoría continúa con la protección de derechos de las comunidades en el Catatumbo’, 12 March. Departments where these atrocities are common include Cauca (ten targeted killings of leaders from 1 July 2024 to 4 April 2025) and Antioquia (thirteen over the same period),93Indepaz, ‘Visor de Asesinato a Personas Líderes Sociales y Defensores de Derechos Humanos en Colombia’.as well as in Arauca, Nariño, Putumayo, and Valle del Cauca.94‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/968, 26 December 2024, para 45; and UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 38. Other departments have also been affected, such as Huila, where on 26 August 2024, Carlos Cerquera, a 39-year-old community leader, was murdered by FARC-EP dissidents in Villa Mercedes de La Plata. His killing followed a meeting in which he had expressed concern about the growing presence of armed groups in the region.95CINEP and Programa por la Paz, ‘Nocha y Niebla 70: Panorama de derechos humanos y violencia política en Colombia’, Banco de Datos de Derechos Humanos y Violencia Política: Julio-Diciembre 2024, p 30.

Although most incidents documented in 2024 were perpetrated by armed groups (and certain unspecified criminal organizations), the Colombian Army was also said to have committed violations. The UN verified 18 allegations of murders committed by police and military forces, including the killing of three Afro-descendant civilians.96‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 37.

In 2024, environmental defenders denouncing the negative environmental effects of activities such as mining and logging, and defending the collective rights of Indigenous and Afro-descendent people, were also murdered by armed groups involved in deforestation, illegal mining, or wildlife trafficking. The UN documented the murder of 25 environmental defenders during the year.97Ibid, para 30. Reports indicate that, in the areas under their control, armed groups profit from deforestation and land control through taxation, extortion, and the appropriation, sale, and use of land. Activities include road construction and the building of trafficking corridors; the establishment of new coca plantations and cattle ranches; and illegal logging, mining, and wildlife trafficking.98In general, see: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, ‘Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet: Colombia’, 3 October 2024. These activities, for which the EMC is particularly known in the remote parts of the Amazon in the departments of Amazonas, Caquetá, Guaviare, and Meta where it enjoys considerable territorial control,99International Crisis Group, ‘Rebel Razing: Loosening the Criminal Hold on the Colombian Amazon’. are said to sustain the group’s military operations.100L. Güiza-Suarez and P. A. Jiménez Rojas, ‘Extracción ilícita de minerals (minería illegal) y financiacíon de grupos armados a través de delitos ambientales’, Consejo Superior de la Judicatura, Escual Judicial “Rodrigo Lara Bonilla” and Universidad del Rosario, April 2022, p 2; L. Güiza-Suarez and C. J. Kaufmann, ‘Justicia ambiental y personas defensoras del ambiente en América Latina’, Report, American Bar Association and Universidad del Rosario, 2024, p 170. See also: R. L. Revelo Suárez, ‘Nuevas Estrategias y Formas de Financiamiento de los Grupos Considerados como Amenaza en la Frontera entre Ecuador y Colombia’, Ciencia Latina Revista Multidisciplinar, Vol 8, No 5 (2024), 4331–53.

A further recurring trend has been the assassination of former FARC-EP members. The UN Verification Mission in Colombia recorded 33 such killings in 2024, with 29 for only the first half of 2025. Such killings total 470 (11 of whom were women) since the signing of the peace agreement with the FARC in 2016.101‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/968, 26 December 2024, para 41; and UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 34. See also ‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 17. According to the UN Verification Mission, most of the killings were perpetrated by armed groups in the departments of Antioquia, Cauca, and Huila. The victims were targeted on account of their leadership roles; their refusal to be recruited into the groups; or their involvement in truth and justice processes.102‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary General’, UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 34.

These and similar killings constitute murder and prima facie war crimes.103Common Art 3, Geneva Conventions of 1949; Art 4(2)(a), Additional Protocol II; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’; and Rule 156: Definition of War Crimes’. Victims are considered to be in the power of a party to the conflict as soon as it exercises ‘a certain level of control over the persons concerned’, which includes living in areas under their control.104Ibid, paras 529–40 and 544–49.

Recruitment of children

Child recruitment and their use to participate in hostilities increased in areas under armed group control in 2024.105ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, pp 4 and 11; UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, pp 3 and 6. While ages are not always specified, some of the victims were under 15 years of age.106Art 4(3), Additional Protocol II; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 136: ‘Recruitment of Child Soldiers’; and Rule 137: ‘Participation of Child Soldiers in Hostilities’. Such recruitment is a serious violation of IHL and a war crime.107ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’. In 2024, OHCHR reported cases of recruitment of girls as young as 12.108‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20. An earlier study by the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar and UNICEF covering the period 2013–22 found that the vast majority of children recruited were between 12 and 17 years of age, with the average age of boys being 14.2 years, and girls being 13.8 years.109UNICEF and Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, ‘Estudio de caracterización de niñez desvinculada de grupos armados organizados en Colombia (2013–2022)’, Report, 2023, p 26.

The United Nations recorded at least 450 children of all ages (179 boys, 166 girls, 5 sex unknown) being recruited by armed groups, in particular dissident FARC-EP groups (362, including 156 by the EMC, 15 by the CDF, and 14 by the Segunda Marquetalia), as well as the ELN (56) and the EGC (39). Two children (ages unknown) were also recruited by the Colombian army. Of the total of 450 children recruited, 87 were used in active combat.110‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, para 44. The total number of children who have been recruited and used as soldiers is, however, presumed to be considerably higher than those confirmed and recorded cases.111‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 18. Strategies of recruitment included financial incentives, seduction, use of social networks, and threats. 112ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 11.

With respect to all confirmed child recruitment, 76 per cent of cases occurred in six departments – Arauca, Cauca, Chocó, Huila, Putumayo, and Nariño – with forty per cent of the total occurring in Cauca.113UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 7. Most of the victims were from Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities.114‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 18. Recruited children were victims of sexual violence and corporal punishment, including mutilation, while some were used to recruit other children by force.115Ibid; ‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, paras 45–46; UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 6; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 11.

A number of children were also murdered by their own or a rival group. Instances of child recruits in armed groups being killed as internal reprisals were recorded by OHCHR in 2024, such as two child recruits who were tortured and killed in Guavarie.116‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 18. In 2024, UNICEF noted an increase in instances of torture and killings of child recruits attempting to leave a group or who were suspected of affiliation with a rival group.117UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 3. Child recruits were also victims of enforced disappearances in 2024, with 77 cases documented by the ICRC, including 23 children under the age of fifteen years.118ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 11.

Arbitrary Deprivation of Liberty

Arbitrary deprivation of liberty and hostage-taking, commonly referred to domestically as secuestro (kidnapping),119Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición, ‘Hay futuro si hay verdad: Informe Final de la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición: Tomo 4. have long been used by Colombian armed groups for raising funds as well as for political or military leverage.120Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Beyond Negotiation International Humanitarian Law and its Application to the Conduct of the FARC-EP’, B1303, 1 August 2001. Although the Colombian government and the ELN agreed to suspend extortion-motivated kidnappings in December 2023, incidents persist among armed groups including the ELN (which later denounced the agreement).121Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. ‘IHL in Focus Report: July 2023–June 2024’, pp 62–63.

During the reporting period, governmental bodies registered around 300 kidnappings, with the actual number probably far higher.122Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘La Defensoría del Pueblo exige la liberación inmediata e incondicional de todas las personas secuestradas en Colombia’, Press release, 7 April 2025; Ministerio de Defensa, ‘Seguimiento a indicadores de seguridad y resultados operacionales’, Información Estadística, 31 March 2025. Some, but not all, of these incidents are linked to armed conflict. For example, in April 2025, the government claimed that the ELN continued to deprive of liberty at least 50 people in Catatumbo for allegedly collaborating with the Frente 33 of the EMBF, and another 18 were in a similar situation in the department of Arauca.123Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘La Defensoría del Pueblo exige la liberación inmediata e incondicional de todas las personas secuestradas en Colombia’, Press release, 7 April 2025. Similarly, in Tibú (Catatumbo, Norte de Santander), on 19 March 2025, the Frente 33 of the EMBF detained a peasant leader, Joaquín Enrique Villamizar, accusing him of collaborating with the ELN and possessing ammunition and weapons.124L. Reynoso, ‘La contraofensiva de las disidencias de las FARC reaviva la crisis en el Catatumbo’, El País, 26 March 2025. Mr Villamizar was subsequently released and, as Luis Fernando Niño, senior peace adviser to the Norte de Santander government, has noted, those under the ELN’s territorial control may have no choice but to comply with its orders.125Ibid.

Civilians, including children, were the most common victims of hostage-taking and arbitrary deprivation of liberty. In 2024, the United Nations documented 16 child abductions, attributed notably to the ELN and FARC-EP dissident groups, including the Segunda Marquetalia and the EMC.126‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, para 48. Some abductions have included military victims,127L. J. Acosta and L. Díaz, ‘Liberan a 29 efectivos de las Fuerzas Armadas secuestrados en el suroeste de Colombia’, Reuters, 9 March 2025; ‘Dos soldados fueron secuestrados por presuntos integrantes del ELN en Cúcuta’, El Espectador, 10 April 2025. such as on 22 June 2025, when 57 Colombian soldiers were abducted by individuals wearing civilian clothes in Cauca, reportedly under pressure from the EMC. They were freed the following day by Colombian security forces.128S. Torrado, ‘El Ejército de Colombia denuncia que 57 militares fueron secuestrados por civiles bajo presión de las disidencias en el Cauca’, El País, 23 June 2025; ‘Ejército de Colombia rescata a 57 militares retenidos por pobladores en Cauca’, CNN en Español, 23 June 2025. Several instances of arbitrary detention by the police or the military were also reported in 2024.129Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 38.

These actions typically breach the prohibition of arbitrary deprivation of liberty and, in certain circumstances, of hostage-taking. 130Common Art 3(1)(b), Geneva Conventions of 1949; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 96: ‘Hostage-Taking’; and Rule 99: ‘Deprivation of Liberty’. Under IHL, hostage-taking amounts to a war crime in all armed conflicts.131ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

Enforced Disappearances

In 2024, enforced disappearances related to armed conflicts and violence increased by 13 per cent in comparison with the previous year and affected mainly civilians (82 per cent, 206 cases), with the departments of Arauca, Bolívar, Cauca, Chocó, Nariño, Norte de Santander, and Valle del Cauca accounting for 85 per cent of all documented cases.132ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 8. Instances of missing members of armed groups (44) and, to a lesser extent, members of the Colombian security forces (2) were also recorded in 2024.133Ibid. Prohibited under customary IHL applicable to NIACs,134ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 98: ‘Enforced Disappearance’. enforced disappearances have been described as part of armed groups’ strategy to terrorize the civilian population and, in some instances, as the result of irregular deprivation of liberty, recruitment, murder and/or mismanagement of bodies.135ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 8. In one incident, a communal and social leader from Cubará (Boyacá), Luis Obdulio Ramón, a 59-year-old man, was abducted from his farm, allegedly by the ELN. His body was found a month later.136CINEP and Programa por la Paz, ‘Nocha y Niebla 70: Panorama de derechos humanos y violencia política en Colombia’, Banco de Datos de Derechos Humanos y Violencia Política: Julio-Diciembre 2024, p 29.

Forced Labour

Cases of forced labour, prohibited under IHL applicable to NIACs,137ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 95: ‘Forced Labour’. were also recorded during the reporting period. Notably, according to reports, the Frente 33 of the EMBF set up ‘resocialization camps’ in the Catatumbo region where people deemed to have violated the armed group’s rules were forced to work. One victim, a 35-year-old man, said he was taken from his house on 8 December 2024 and brought to a ‘resocialization camp’ for allegedly collaborating with the Colombian Army, based on a video of a Colombian Army helicopter that he had posted on WhatsApp. According to his testimony, he and 27 other people were forced to cut sugarcane every day from 4 am to 6:30 pm. He witnessed the murder of a couple who were arguing as well as sexual violence perpetrated by commanders of the Frente 33 of the EMBF against women and girls held in the camp.138Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Armed Groups Batter Border Region – Poor Government Protection Exposes Civilians to Abuse’, 26 March 2025.

Conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence

In 2024, the National Victims’ Unit recorded 1,097 cases of conflict-related sexual violence, the overwhelming majority of which were committed against females (1,009 women and girls), but also against males (73), as well as those of diverse sexual orientation and gender identity (15).139‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, 15 July 2025, para 27. These figures represent a 68 per cent increase over 2023, with most cases recorded in the departments of Antioquia, Bolívar, Cauca, Chocó, Nariño, and Valle del Cauca.140Ibid. The UN has reported that gender-based and sexual violence forms part of armed groups’ strategies of social control – serving to deter civilians from joining opposing groups and to punish women human rights defenders and LGBTIQ+ persons, who are seen as obstacles to the armed groups’ ideology and control – as well as a source of illicit income through human trafficking for sexual exploitation.141Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20; ‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27.

Indigenous persons, Afro-descendants, migrants, child recruits and, more broadly, confined populations are the primary victims of sexual violence,142‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20; ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, pp 12–13 and 17; ‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-general’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27. with Indigenous and Afro-descendants accounting for 37 per cent of the total number of cases.143‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27. Instances of rape, child marriage, and forced contraception committed against recruited girls as young as 12 years of age were reported in 2024.144‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20. Of the forty-nine children who were victims of sexual violence documented by the United Nations in 2024, three were boys.145‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27. While most abuses were attributed to armed groups – in particular the EGC, the ELN, FARC-EP dissident factions, including the EMBF – the United Nations has also verified allegations of gender-based and sexual violence by members of the Colombian security forces.146Ibid, paras 27 and 38.

Under-reporting of gender-based and sexual violence remains significant, driven by the normalization of such violence, the stigmatization of survivors, and limited access to legal and medical support services. Nonetheless, OHCHR received multiple reports of trafficking and sexual exploitation of women and girls in locations under the control of armed groups in Antioquia, El Chocó, Nariño, and Norte de Santander.147‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20. OHCHR also documented murders, threats, displacement, and attacks against individuals based on their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.148‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20.

The above incidents constitute sexual violence, which is explicitly prohibited under IHL as violence to life and person and outrages upon personal dignity.149Common Art 3; Art 4(2)(e) and (f), Additional Protocol II. The prohibition covers rape, enforced prostitution, and other forms of sexual violence, as well as similarly cruel or degrading treatment. These prohibitions are enshrined in treaty and customary law, and serious violations are war crimes.150ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

In some instances, armed groups employed sexual mutilation to terrorize populations.151Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición, ‘Hay futuro si hay verdad: Informe Final de la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición: Tomo 4. Hasta la guerra tiene límites. Violaciones de los derechos humanos, infracciones al derecho internacional humanitario y responsabilidades colectivas’. This has been identified as the second most common form of sexual violence perpetrated against men.152Ibid. Women have reportedly been forced to witness such acts to intimidate male relatives and deter enlistment in rival groups.153Ibid. In addition to being war crimes as sexual violence, this may also constitute acts of terrorism under IHL and international criminal law.154Art 4(2), Additional Protocol II; and Art 4(d), Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Treatment of persons with disabilities

According to official data, 4.5 per cent of Colombia’s population over five years of age live with a disability,155In Colombia, Law 1618 of 2013 defines persons with disabilities as people with ‘physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments to medium’ and whose interaction with various barriers ‘may impede their full and effective participation in society, on an equal footing with others.’ with visual impairments the most prevalent.156Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE), ‘Nota estadística, estado actual de la medición de discapacidad en Colombia’, Bogotá, 2022; see M. Pinilla-Roncancio and G. Cedeño-Ocampo, ‘Multidimensional poverty among persons with disabilities in Colombia: Inequalities in the distribution of deprivations at the municipality level’, PLoS One, Vol 18, No 6 (29 June 2023), e0286983. Colombia adhered to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2011. The Convention requires that the State take, in accordance with IHL and international human rights law, ‘all necessary measures’ to ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in armed conflict.157Art 11, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; adopted at New York, 13 December 2006; entered into force, 3 May 2008. Persons with disabilities have been largely excluded from peace talks in the past, with those with psycho-social and intellectual impairments said to remain ‘invisible members of the society’.158B. Caltabiano, ‘Disability and Armed Conflict, Episode 3’, L’Osservatorio; and see Disability and Armed Conflict: Field Trip to Colombia, Geneva Academy, March 2017. In July 2025, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, Heba Hagrass, urged Colombia to translate its robust legal framework into concrete actions and for the authorities to disaggregate data based on disability.159OHCHR, ‘Despite legal progress, full inclusion of persons with disabilities in Colombia remains an unfulfilled promise: UN expert’, Press release, 25 July 2025.

The widespread use of anti-personnel mines and IEDs inevitably causes significant numbers of traumatic amputation and the survivors need lifelong care in order to reintegrate effectively into society. International NGO Humanity & Inclusion (HI) provides rehabilitation and mental health and psychosocial support for both armed conflict and migration settings.160HI, ‘Colombia Country Sheet’, September 2024. In northern Colombia, HI assisted more than 20,600 people in 2024, with nearly 7,000 receiving physiotherapy, crutches, and/or prostheses, and 4,800 receiving psycho-social support.161HI, ‘Developing access to rehabilitation in Colombia’, 10 February 2025.

- 1Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición, ‘La Desmovilización de las AUC’.

- 2

- 3European Union, ‘An Historical Peace Agreement in Colombia’, 23 April 2021.

- 4S. Torrado, ‘Proceso de paz con el ELN: fin del cese al fuego, secuestro y suspensión de los diálogos con el Gobierno Petro’, El País, 6 February 2025.

- 5‘Catatumbo: así avanza la salida de la crisis, tras dos meses de escalada violenta’, El Espectador, 14 March 2025.

- 6J. P. Contreras Ríos, ‘No ocurre solo en Catatumbo: las alarmas por desborde de desplazamiento forzado’, El Espectador, 17 February 2025.

- 7International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), ‘Humanitarian Report 2025 – Colombia’.

- 8The EMC sprang from an original group of 60 or so FARC-EP members who did not adhere to the 2016 peace process. In 2024, after disagreements between EMC membership on the desirability of new peace negotiations with the Colombian government, the EMBF was formed as a splinter group. J. P. Contreras Ríos, ‘Así nació el grupo que se separó de Mordisco y que ahora negocia la paz con Petro’, El Espectador, 4 December 2024.

- 9As of June 2024, according to Human Rights Watch, the EGC was present in 392 municipalities; the ELN in 232; and dissident FARC-EP groups in 299. Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Events of 2024’, World Report 2025.

- 10The material jurisdiction of the Protocol is limited to armed conflicts ‘which take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups.…’ [added emphasis]. Art 1(1), Additional Protocol II of 1977.

- 11The Colombian government’s ‘Total Peace’ policy was instituted under Law 2272 of 2022 as a strategic decision to seek peace with all armed groups active in the country. The policy also seeks implementation of previously concluded peace agreements. Departamento Nacional de Planeación, ‘Paz Total’, 16 June 2025.

- 12Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Events of 2024’.

- 13ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, 27 March 2025, p 3.

- 14Ibid, p 3 ff.

- 15United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Colombia: Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan: Update – Summary’, January 2025, p 4.

- 16Ibid, p 3.

- 17ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 7: ‘The Principle of Distinction between Civilian Objects and Military Objectives’.

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, 17 June 2025, para 47.

- 23Ibid.

- 24‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, 22 January 2025, para 19.

- 25ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 3.

- 26UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, 2025, p 8.

- 27Ibid.

- 28Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), ‘Integrated Mine Action Program Phase 1: 2021-2025’.

- 29Colombia Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention Article 7 Report (for 2024), p 63.

- 30Colombia, Article 5 deadline Extension Request under the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, 5 June 2025, p 4.

- 31‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 19.

- 32C. Salazar, ‘Niña de 9 años resultó herida tras caer en un campo minado en San Vicente del Caguán, Caquetá’, Infobae, 24 August 2024.

- 33J. Sampier, M. R. Tortosa and E. Breyne, ‘Mapping and Profiling the Most Threatening Criminal Networks in Latin America and the Caribbean’, El Paccto, 2025, pp 25 and 74.

- 34ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, Thematic report, 10 July 2025, p 12.

- 35

- 36ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 4.

- 37Ibid, pp 3–5.

- 38Mine Action Review, ‘Colombia’, Clearing the Mines 2025, Norwegian People’s Aid, November 2025.

- 39Art 1(1), Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention. Colombia became a State Party on 1 March 2001.

- 40Art 1(2), Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 annexed to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; adopted at Geneva, 3 May 1996; entered into force, 3 December 1998. Colombia adhered to the Protocol in 2000.

- 41Art 3(8) and (10), 1996 Amended Protocol II.

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 5.

- 47ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 12.

- 48S. Torrado, ‘Colombia on alert as dissident groups ramp up drone attacks’, El País, 1 September 2025.

- 49Ibid.

- 50ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 12; Torrado, ‘Colombia on alert as dissident groups ramp up drone attacks’.

- 51ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 5; Torrado, ‘Colombia on alert as dissident groups ramp up drone attacks’.

- 52Ibid.

- 53Iván Velásquez Gómez, Post on social media site X, 24 July 2024; C. McGowan, ‘Ten-year-old boy killed in Colombia’s first drone death’, BBC News, 25 July 2024; ‘10-year-old boy on soccer field killed in “cowardly terrorist attack” targeting soldiers in Colombia’, CBS News, 25 July 2024.

- 54

- 55ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 23: ‘Location of Military Objectives outside Densely Populated Areas’; and Rule 24: ‘Removal of Civilians and Civilian Objects from the Vicinity of Military Objectives’.

- 56J. F. Rodríguez, ‘Disidencias Farc estarían usando civiles como escudo en enfrentamientos en el Catatumbo’, W Radio Colombia, 23 March 2025; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025, Colombia’, p 6.

- 57‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 16. See also: ‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/968, 26 December 2024, para 39; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 6.

- 58ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, pp 13–16; L. Reynoso, ‘La contraofensiva de las disidencias de las FARC reaviva la crisis en el Catatumbo’, El País, 26 March 2025; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 6.

- 59ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, pp 10–13.

- 60Ibid, pp 10–11.

- 61ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 6.

- 62‘“Paren esta guerra tan dura”: comunidades alertan por aumento de violencia en Chocó’, El Espectador, 9 February 2025.

- 63ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 10.

- 64‘“Paren esta guerra tan dura”: comunidades alertan por aumento de violencia en Chocó’

- 65ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 6.

- 66Rodríguez, ‘Disidencias Farc estarían usando civiles como escudo en enfrentamientos en el Catatumbo’.

- 67International Crisis Group, ‘Rebel Razing: Loosening the Criminal Hold on the Colombian Amazon’, 18 October 2024.

- 68‘Central General Staff – FARC Dissidents’, InSight Crime, 14 June 2024.

- 69OCHA, ‘Colombia: Informe de situación humanitaria 2024 – enero a noviembre de 2024’, 31 December 2024.

- 70Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘Emergencias humanitarias en Colombia hoy’, 16 February 2025. See also T. Breda, ‘“Total Peace” paradox in Colombia: Petro’s policy reduced violence, but armed groups grew stronger’, ACLED, 28 November 2024; ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, p 13.

- 71‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 15; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 7.

- 72ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 7.

- 73Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘Emergencias humanitarias en Colombia hoy’, 16 February 2025.

- 74Contreras Ríos, ‘No ocurre solo en Catatumbo: las alarmas por desborde de desplazamiento forzado’.

- 75J. P. Contreras Ríos, ‘Los focos de violencia en el país que podrían desatar una crisis como en Catatumbo’, El Espectador, 8 February 2025.

- 76P. Mesa Loaiza, ‘Viaje al Catatumbo: así se vive la mayor crisis humanitaria de los últimos tiempos’, El Espectador, 26 January 2025.

- 77ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 7. See also Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘Colombia days in limbo amid escalating armed conflict’, 14 February 2025.

- 78

- 79

- 80M. Sassòli, International Humanitarian Law: Rules, Controversies, and Solutions to Problems Arising in Warfare, 2nd edn,Edward Elgar, 2024, para 10.240.

- 81OCHA, ‘Colombia: Informe de Situación Humanitaria 2025 : Entre enero y abril de 2025’, 5 June 2025, p 2.

- 82ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 4; UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 4.

- 83‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 24.

- 84Ibid, para 28.

- 85Ibid.

- 86Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Indepaz), ‘Visor de Asesinato a Personas Líderes Sociales y Defensores de Derechos Humanos en Colombia’.

- 87‘Visit to Colombia: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay’, UN Doc A/HRC/57/47/Add.1, 10 September 2024, paras 57 and 58; ‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, paras 7, 13, 25, 28, and 29; B. M. Arango Jiménez, ‘Los patrones de persecución a líderes sociales después de la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz en el 2016’, Revista Nova et Vetera, Vol 7, No 66 (2021); ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 4.

- 88‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, paras 25–26.

- 89Ibid, paras 28 and 29.

- 90‘14 guerrilleros habrían muerto en combate entre ELN y FARC En zona rural del municipio de Arauquita’, News Radio, 13 August 2024; International Crisis Group, ‘Colombia’, June 2025; ‘Emergencias humanitarias en Colombia hoy’, Defensoría del pueblo: Colombia, 16 February 2025; J. D. Rodríguez, ‘Defensoría del Pueblo alerta por combates del ELN y disidencia de ‘Iván Mordisco’ en Arauca’, Infobae, 23 February 2025.

- 91‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary General’, UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 38.

- 92IMPACT, ‘Urgent Need for a Sustainable Response amid Escalating Violence and Persistent Insecurity in Catatumbo’, February 2025; Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘Defensoría continúa con la protección de derechos de las comunidades en el Catatumbo’, 12 March.

- 93

- 94‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/968, 26 December 2024, para 45; and UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 38.

- 95CINEP and Programa por la Paz, ‘Nocha y Niebla 70: Panorama de derechos humanos y violencia política en Colombia’, Banco de Datos de Derechos Humanos y Violencia Política: Julio-Diciembre 2024, p 30.

- 96‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 37.

- 97Ibid, para 30.

- 98In general, see: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, ‘Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet: Colombia’, 3 October 2024.

- 99International Crisis Group, ‘Rebel Razing: Loosening the Criminal Hold on the Colombian Amazon’.

- 100L. Güiza-Suarez and P. A. Jiménez Rojas, ‘Extracción ilícita de minerals (minería illegal) y financiacíon de grupos armados a través de delitos ambientales’, Consejo Superior de la Judicatura, Escual Judicial “Rodrigo Lara Bonilla” and Universidad del Rosario, April 2022, p 2; L. Güiza-Suarez and C. J. Kaufmann, ‘Justicia ambiental y personas defensoras del ambiente en América Latina’, Report, American Bar Association and Universidad del Rosario, 2024, p 170. See also: R. L. Revelo Suárez, ‘Nuevas Estrategias y Formas de Financiamiento de los Grupos Considerados como Amenaza en la Frontera entre Ecuador y Colombia’, Ciencia Latina Revista Multidisciplinar, Vol 8, No 5 (2024), 4331–53.

- 101‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2024/968, 26 December 2024, para 41; and UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 34. See also ‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 17.

- 102‘United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia: Report of the Secretary General’, UN Doc S/2025/419, 27 June 2025, para 34.

- 103Common Art 3, Geneva Conventions of 1949; Art 4(2)(a), Additional Protocol II; ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 89: ‘Violence to Life’; and Rule 156: Definition of War Crimes’

- 104Ibid, paras 529–40 and 544–49.

- 105ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, pp 4 and 11; UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, pp 3 and 6.

- 106Art 4(3), Additional Protocol II; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 136: ‘Recruitment of Child Soldiers’; and Rule 137: ‘Participation of Child Soldiers in Hostilities’.

- 107ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 108‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20.

- 109UNICEF and Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, ‘Estudio de caracterización de niñez desvinculada de grupos armados organizados en Colombia (2013–2022)’, Report, 2023, p 26.

- 110‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, para 44.

- 111‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 18.

- 112ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 11.

- 113UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 7.

- 114‘Situation of human rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 18.

- 115Ibid; ‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, paras 45–46; UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 6; ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, p 11.

- 116‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 18.

- 117UNICEF, ‘Informe del Secretario General de Naciones Unidas sobre 2024 niñez y conflictos armados: capítulo Colombia’, p 3.

- 118ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 11.

- 119Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición, ‘Hay futuro si hay verdad: Informe Final de la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición: Tomo 4.

- 120Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Beyond Negotiation International Humanitarian Law and its Application to the Conduct of the FARC-EP’, B1303, 1 August 2001.

- 121Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. ‘IHL in Focus Report: July 2023–June 2024’, pp 62–63.

- 122Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘La Defensoría del Pueblo exige la liberación inmediata e incondicional de todas las personas secuestradas en Colombia’, Press release, 7 April 2025; Ministerio de Defensa, ‘Seguimiento a indicadores de seguridad y resultados operacionales’, Información Estadística, 31 March 2025.

- 123Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia, ‘La Defensoría del Pueblo exige la liberación inmediata e incondicional de todas las personas secuestradas en Colombia’, Press release, 7 April 2025.

- 124L. Reynoso, ‘La contraofensiva de las disidencias de las FARC reaviva la crisis en el Catatumbo’, El País, 26 March 2025.

- 125Ibid.

- 126‘Children and armed conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc A/79/878-S/2025/247, para 48.

- 127L. J. Acosta and L. Díaz, ‘Liberan a 29 efectivos de las Fuerzas Armadas secuestrados en el suroeste de Colombia’, Reuters, 9 March 2025; ‘Dos soldados fueron secuestrados por presuntos integrantes del ELN en Cúcuta’, El Espectador, 10 April 2025.

- 128S. Torrado, ‘El Ejército de Colombia denuncia que 57 militares fueron secuestrados por civiles bajo presión de las disidencias en el Cauca’, El País, 23 June 2025; ‘Ejército de Colombia rescata a 57 militares retenidos por pobladores en Cauca’, CNN en Español, 23 June 2025.

- 129Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 38.

- 130Common Art 3(1)(b), Geneva Conventions of 1949; and ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 96: ‘Hostage-Taking’; and Rule 99: ‘Deprivation of Liberty’.

- 131ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 132ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 8.

- 133Ibid.

- 134

- 135ICRC, ‘Humanitarian Challenges 2025 – Colombia’, Report, p 8.

- 136CINEP and Programa por la Paz, ‘Nocha y Niebla 70: Panorama de derechos humanos y violencia política en Colombia’, Banco de Datos de Derechos Humanos y Violencia Política: Julio-Diciembre 2024, p 29.

- 137

- 138Human Rights Watch, ‘Colombia: Armed Groups Batter Border Region – Poor Government Protection Exposes Civilians to Abuse’, 26 March 2025.

- 139‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, 15 July 2025, para 27.

- 140Ibid.

- 141Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20; ‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27.

- 142‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20; ACAPS, ‘Colombia: Confinement and mobility restrictions in Caquetá, Cauca, and Chocó’, pp 12–13 and 17; ‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-general’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27.

- 143‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27.

- 144‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20.

- 145‘Conflict-related sexual violence: Report of the Secretary-General’, UN Doc S/2025/389, para 27.

- 146Ibid, paras 27 and 38.

- 147‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20.

- 148‘Situation of Human Rights in Colombia: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’, UN Doc A/HRC/58/24, para 20.

- 149Common Art 3; Art 4(2)(e) and (f), Additional Protocol II.

- 150ICRC, Customary IHL Rule 93: ‘Rape and Other forms of Sexual Violence’; and Rule 156: ‘Definition of War Crimes’.

- 151Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición, ‘Hay futuro si hay verdad: Informe Final de la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición: Tomo 4. Hasta la guerra tiene límites. Violaciones de los derechos humanos, infracciones al derecho internacional humanitario y responsabilidades colectivas’.

- 152Ibid.

- 153Ibid.

- 154Art 4(2), Additional Protocol II; and Art 4(d), Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

- 155In Colombia, Law 1618 of 2013 defines persons with disabilities as people with ‘physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments to medium’ and whose interaction with various barriers ‘may impede their full and effective participation in society, on an equal footing with others.’

- 156Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE), ‘Nota estadística, estado actual de la medición de discapacidad en Colombia’, Bogotá, 2022; see M. Pinilla-Roncancio and G. Cedeño-Ocampo, ‘Multidimensional poverty among persons with disabilities in Colombia: Inequalities in the distribution of deprivations at the municipality level’, PLoS One, Vol 18, No 6 (29 June 2023), e0286983.

- 157Art 11, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; adopted at New York, 13 December 2006; entered into force, 3 May 2008.

- 158B. Caltabiano, ‘Disability and Armed Conflict, Episode 3’, L’Osservatorio; and see Disability and Armed Conflict: Field Trip to Colombia, Geneva Academy, March 2017.

- 159OHCHR, ‘Despite legal progress, full inclusion of persons with disabilities in Colombia remains an unfulfilled promise: UN expert’, Press release, 25 July 2025.

- 160HI, ‘Colombia Country Sheet’, September 2024.

- 161HI, ‘Developing access to rehabilitation in Colombia’, 10 February 2025.